Generating a comprehensive understanding of the health problem requires the identification of influential factors and the delineation of their inter‐relationships with the problem.

Identification of Factors

Causative factors, risk factors, or determinants of the health problem are circumstances, events, conditions, or capabilities that contribute to its experience. It is now well recognized that multiple factors, taking place at different levels, conduce to the occurrence (e.g. Aráujo‐Soares et al., 2018; Golfam et al., 2015) or maintenance (e.g. Glanz & Bishop, 2010) of a particular problem. The factors exhibit in any domain of health and life, at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, and environmental levels (Bartholomew et al., 2016). Intrapersonal factors include biological characteristics (e.g. sex and age) and physiological, physical, behavioral, psychological, and cognitive conditions. Interpersonal factors entail challenges in the relationships between individual clients and others in their immediate environment (e.g. home, work) and the availability or accessibility of resources and support. Social factors relate to beliefs, values, and norms commonly held by a group or community. Environmental factors represent features of the physical, socioeconomic, and political setting or context in which clients reside (Craig et al., 2018).

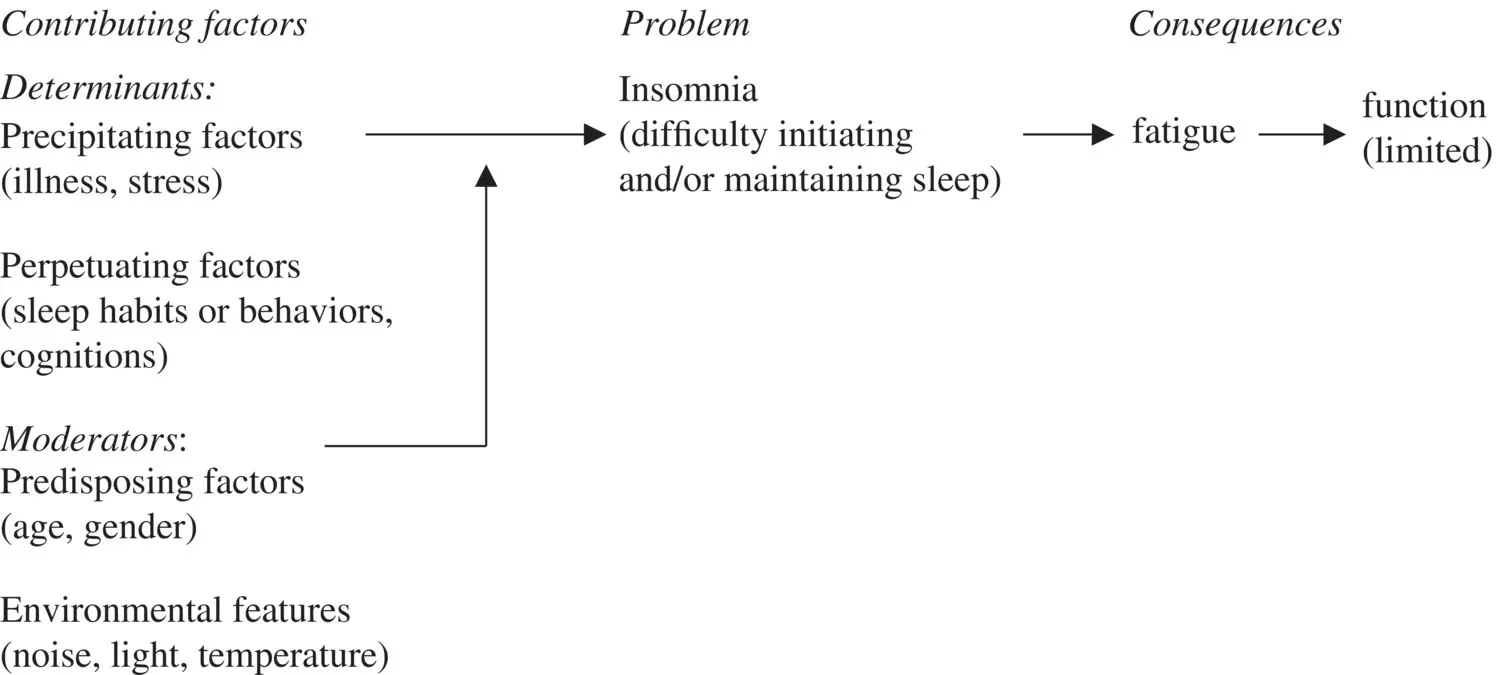

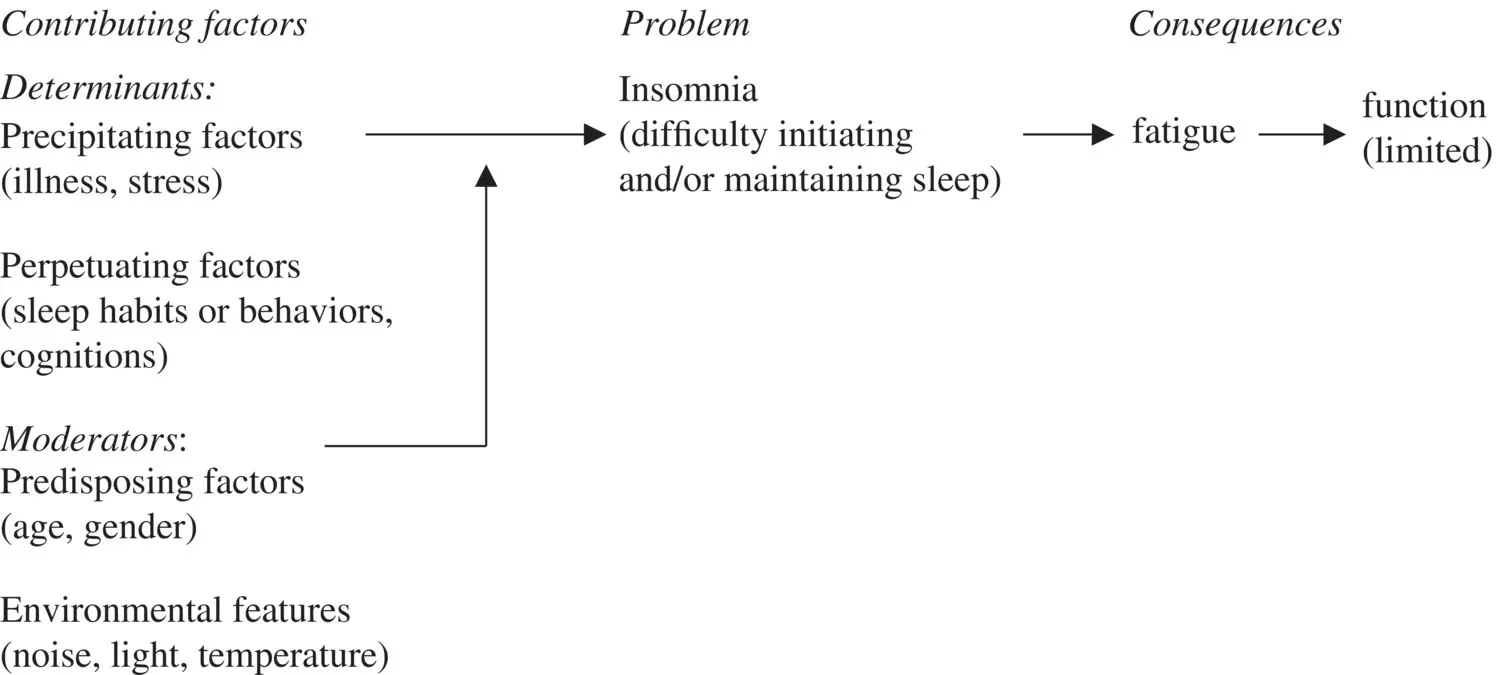

In addition to identifying the types and levels at which the factors occur, it may be useful to (1) categorize them into factors that contribute to the development or to the maintenance of the health problem (Butner et al., 2015; Glanz & Bishop, 2010); (2) determine if and how they are inter‐related and (3) if they vary across populations and time. Overall, the factors can be categorized into predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors as was done for factors contributing to insomnia.

1 Predisposing factors are usually innate characteristics that increase clients' susceptibility or tendency to experience the problem. This category of factors is illustrated with sex and age, which have been found to increase clients' vulnerability to experience insomnia.

2 Precipitating (also called enabling) factors are conditions or events that bring about or trigger the problem. This category of factors is illustrated with the onset of illness or stress‐related events that disrupt sleep.

3 Perpetuating (also called reinforcing) factors serve to maintain the problem. In the case of insomnia, perpetuating factors represent sleep habits or behaviors that clients engage in an attempt to deal with poor sleep but are ineffective.

Delineation of Inter‐relationships

In the real world, the determinants are interconnected, forming a web of factors contributing to the experience of the health problem. The determinants can co‐occur simultaneously or sequentially, and interact with each other to produce the health problem. For instance, older persons are prone to arousability (i.e. light sleep), which may be exacerbated if they reside in a noisy neighborhood (simultaneous); they start drinking alcohol (sequential) thinking that it would help them sleep better; alcohol causes light sleep thereby further contributing to awakenings at night, and intensifies the effects of medications such as sleeping pills and other antidepressants (interaction). The specific determinants or combination of factors contributing to the health problem could vary across client populations or within the same population over time. For example, young and middle‐aged adults (compared to older adults) report difficulty falling asleep, which they attribute to stress related to daily life and work; the level at which they experience this sleep difficulty fluctuates over time as a result of changes in life and work events and clients' use of effective strategies to promote sleep (e.g. engagement in relaxation).

The identification and the specification of the inter‐relationships among determinants are essential for understanding why and how the health problem is generated and maintained. A critical analysis of the inter‐relationships (described in Chapter 4) assists in determining the factors that are and are not amenable to change (Aráujo‐Soares et al., 2018; Bartholomew et al., 2016; Fernandez et al., 2019; Lippe & Ziegelman, 2008). Factors that are malleable and have the greatest scope for change are targeted by the intervention (Wight et al., 2016); they inform the specification of its active ingredients. Factors that cannot be modified (e.g. personal and contextual characteristics) are considered as potential moderators, indicating the need for tailoring of the intervention (Fleury & Sidani, 2018).

3.2.2 Consequences of the Problem

Consequences of the health problem represent complications that may arise if the problem is not effectively addressed. Complications are changes in condition resulting from the problem and interfering with clients' general functioning, health and well‐being. Examples of consequences associated with insomnia include: physical and mental fatigue that limit physical and psychosocial functioning, which in turn, contributes to accidents. The experience of consequences may be the reason for which clients seek healthcare. As such, interventions are designed to address the health problem with the ultimate goal of preventing or minimizing the severity of its consequences.

3.2.3 Illustrative Example

Once developed, the theory or logic model of the health problem is presented textually to detail the conceptual and operational definitions of the problem; identify and describe its determinants and consequences; and explain the proposed direct and indirect (mediated and/or moderated) relationships among them. The theory is also summarized in a table and its main propositions illustrated in a figure. Table 3.1and Figure 3.1illustrate the theory of insomnia.

3.3 APPROACHES FOR GENERATING THEORY OF THE HEALTH PROBLEM

Different approaches can be utilized, independently or in combination, to gain an understanding of the health problem and generate a theory of the problem. The approaches include theoretical, empirical, and experiential. They reflect different logic and methods of reasoning: deductive (top‐down), inductive (bottom‐up), retroductive (backtracking process of logical inference going beyond an existing theory and empirical observations), and abductive (alternative explanation process). The approaches can be used independently. With the emphasis on evidence‐based practice, the empirical approach was considered the most robust. With the recent emphasis on client engagement in the design of health services and in research, and the widening recognition of the role of context in health and healthcare, the experiential approach has been increasingly advocated. Since each approach has its strengths and limitations, the use of a combination of approaches is recommended (e.g. Aráujo‐Soares et al., 2018; Bartholomew et al., 2016; Bleijenberg et al., 2018) to develop a comprehensive understanding of the health problem as experienced by the target client population in the respective context. The approaches and methods for applying them are discussed next.

TABLE 3.1 Summary of the theory of insomnia.

| Conceptual definition |

Nature |

Insomnia is conceptualized as a learned behavior Insomnia refers to self‐reported disturbed sleep in the presence of adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep Insomnia is actually experienced by clients across the life span |

| Operational definition |

Defining indicators |

Types: Insomnia is manifested in any or a combination of difficulty initiating or maintain sleep Levels: Sleep difficulties reported at ≥30 minutes per night, reported on ≥3 nights per week |

|

Severity |

Insomnia Severity Index total score: ≤7 = no clinically significant insomnia 8–14 = subthreshold insomnia 15–21 = clinical insomnia of moderate severity 22–28 = clinically severe insomnia |

|

Duration |

Acute insomnia: indicators experienced at the specified level, periodically for <3 months Chronic insomnia: indicators experienced at the specified level for ≥3 months |

| Contributing factors |

Determinants |

Precipitating factors: onset of illness, stress, life or work‐related events that disrupt sleep |

|

|

Perpetuating factors: cognitions (unrealistic beliefs about sleep, insomnia and its consequences); general behaviors (physical inactivity, smoking); sleep habits or behaviors (irregular sleep schedules, engaging in activities in bed); and engagement in behaviors (extended time in bed) that fuel or maintain insomnia |

|

Moderators |

Predisposing factors: innate characteristics (age, sex, familial or genetic tendency) that increase vulnerability to poor sleep |

|

Environment |

Features (light, noise, temperature) in the sleep environment that interfere with good sleep |

| Consequences |

|

Physical and mental daytime fatigue; reduced engagement in physical and psychosocial functions; home, work, or traffic accidents; development of physical (e.g. hypertension) and psychological (e.g. depression) health conditions |

FIGURE 3.1 Representation of theory of insomnia.

Читать дальше