Michael Graham - Wind Energy Handbook

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Graham - Wind Energy Handbook» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Wind Energy Handbook

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Wind Energy Handbook: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Wind Energy Handbook»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

delivers a fully updated treatment of key developments in wind technology since the publication of the book’s Second Edition in 2011. The criticality of wakes within wind farms is addressed by the addition of an entirely new chapter on wake effects, including ‘engineering’ wake models and wake control. Offshore, attention is focused for the first time on the design of floating support structures, and the new ‘PISA’ method for monopile geotechnical design is introduced.

The coverage of blade design has been completely rewritten, with an expanded description of laminate fatigue properties and new sections on manufacturing methods, blade testing, leading-edge erosion and bend-twist coupling. These are complemented by new sections on blade add-ons and noise in the aerodynamics chapters, which now also include a description of the Leishman-Beddoes dynamic stall model and an extended introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics analysis.

The importance of the environmental impact of wind farms both on- and offshore is recognised by extended coverage, which encompasses the requirements of the Grid Codes to ensure wind energy plays its full role in the power system. The conceptual design chapter has been extended to include a number of novel concepts, including low induction rotors, multiple rotor structures, superconducting generators and magnetic gearboxes.

References and further reading resources are included throughout the book and have been updated to cover the latest literature. Importantly, the core subjects constituting the essential background to wind turbine and wind farm design are covered, as in previous editions. These include:

The nature of the wind resource, including geographical variation, synoptic and diurnal variations and turbulence characteristics The aerodynamics of horizontal axis wind turbines, including the actuator disc concept, rotor disc theory, the vortex cylinder model of the actuator disc and the Blade-Element/Momentum theory Design loads for horizontal axis wind turbines, including the prescriptions of international standards Alternative machine architectures The design of key components Wind turbine controller design for fixed and variable speed machines The integration of wind farms into the electrical power system Wind farm design, siting constraints and the assessment of environmental impact Perfect for engineers and scientists learning about wind turbine technology, the

will also earn a place in the libraries of graduate students taking courses on wind turbines and wind energy, as well as industry professionals whose work requires a deep understanding of wind energy technology.

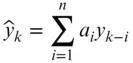

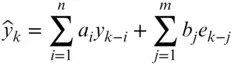

is the prediction for the next step.

is the prediction for the next step.