The civil wars in Mozambique and Angola allowed poachers to all but wipe out the wild animals. The researchers thus approached their expedition to Sudan with grave trepidations.33 The animal population found in northwestern area of Southern Sudan turned out in fact to have been ravaged by poachers. This was also the case in Boma national park, which is located in the southeast of the area. The gigantic herds of buffaloes and zebras had been completely decimated.34 Reports were received on a frequent basis of the Jajanweed’s slaughtering of entire herds of elephants—for their ivory—found in neighboring countries.35 The Sudd is impassible. And that obviously hindered the region’s penetration by poachers. The swamp became the shield protecting the animals of Southern Sudan.36

The roads leading to the oil fields intersect the animals’ traditional paths of migration. This was a concern of the nature protectors. It took seemingly a miracle to protect the animals from destruction during the war. The animals saved by this miracle are now threatened with being the victims of the post-war era. The Sudd serves another purpose. It makes the region absolutely indispensable. Viewed hydrologically, the Sudd is a huge filter that monitors and normalizes the quality of the water passing through it. The Sudd is like a huge sponge. It thus stabilizes the water’s flowage. The wetlands are the main source of the water needed by humans and animals. It is also a rich source of fish. The Sudd’s inhabitants belong mostly to the Dinka, Nuer and Shilluk ethnic groups. Their lives, livelihoods and cultural activities are completely dominated by the seasons, and particularly by the alternating between dry and wet weather. The rainy season enables the recovery of the meadows on which the cattle graze. The local people leave their homes upon the commencement on the dry season. These homes are located in the highlands. They and their livestock migrate to the lowlands.

The beginning of the rainy season, which generally comes in May or June, causes them to return to their villages.37 One of the reasons for the civil war between north and south’s breaking out once more was the plan to dry out the Sudd. This would have been done through the building of a canal. It would have enabled the Nile’s water to flow to the north.38 This would have stripped the south’s people of the wellspring of their lives. It was as early as 2006 that the exploitation of oil reserves was recognized to be a threat to this unique ecosystem. The pumping of oil was launched for the first time in the same year. Has this peril in fact become—so very quickly—a reality? We are going to look at the mater in depth.

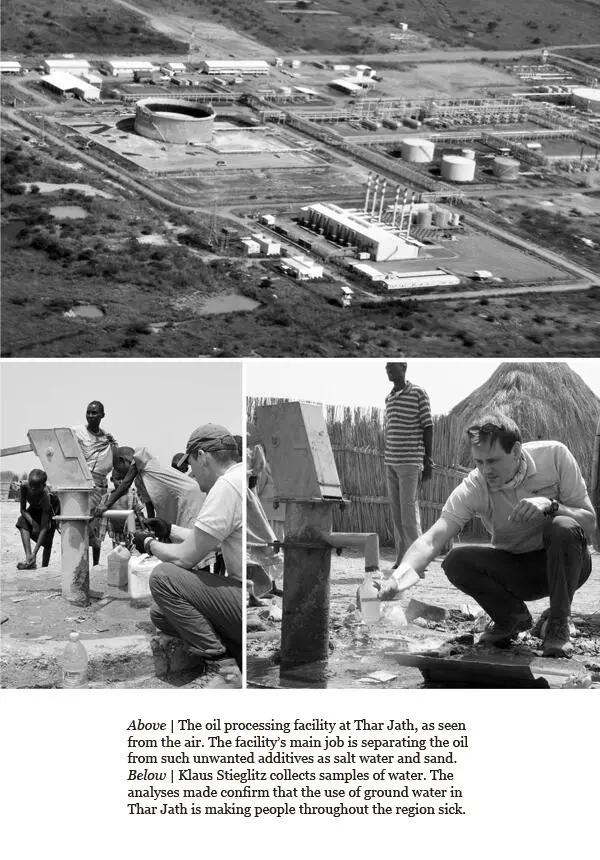

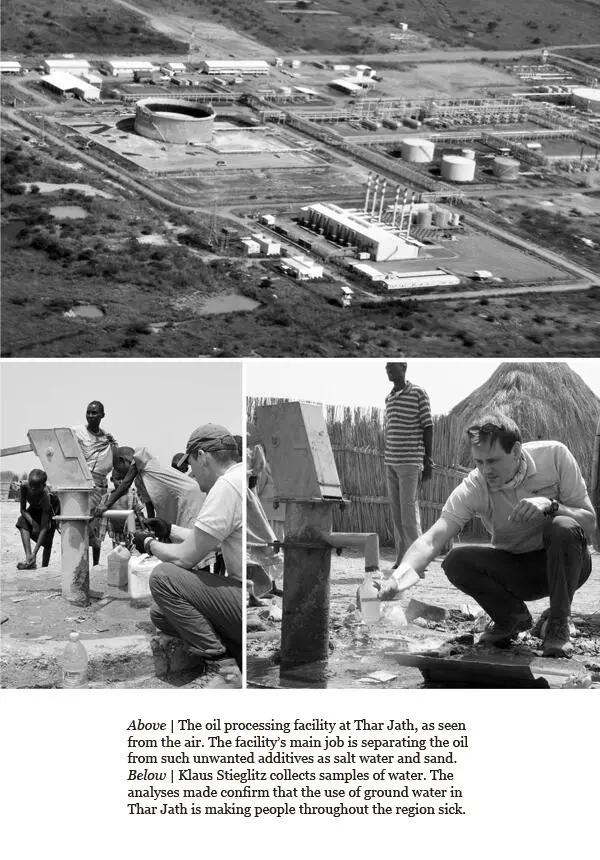

The first evidence of the change takes the form of the rusted signs placed on the side of the road. They indicate the presence of oil fields. The next sight is—fully unexpectedly—the appearance of high voltage lines. We pass every more frequently oil pumps protected by rings of barbed wire. We are now in the middle of the Thar Jath oil fields. And suddenly, from out of nowhere, six smokestacks appear in front of us. Each has a pattern of red and white rings. They form part of the refinery whose construction has been completed a couple of months previously. The refinery has been commissioned a few weeks earlier. Issuing from two of the stacks are dark clouds of pollutants. The unpainted metal expanses found on pipes, tanks and buildings reflect the blinding sunlight. The facility is fenced in. The watchtowers placed on the corners are scary.

We drive past the facility. Six and a half kilometers down the road is Rier, where we meet with lots of the local residents, and takes notes of these discussions. This Rier is new. The old village was destroyed to make room for a facility for the pumping of oil. The town’s 3,500 residents were forced in 2005 by the Khartoum regime to immediately leave. The residents say that North Sudan was in control of their region until the beginning of the year. They received neither indemnification nor assistance in the construction of their new homes.

The new Rier feels like a refugee camp. It has hardly anything of a time-crafted homeland. In contrast to other communities, the first step in the building of this one was not the construction of the tukuls—the abode huts—and then the laying out of the paths connecting the clumps of houses. In the “new” Rier, the streets were first laid out in a strict grid. Hutches for the residents were then constructed along these roads. The expelling of these people from their town is yet another alarming breach of basic human rights.

One special source of concern is the quality of the water available for drinking. A hand-operated pump is supposed to transport the water out of the ground. But the residents of Rier do not use this water any more. They assume that the water has been contaminated by the chemicals released by the oil companies. A young girl reports: “The water is bitter. We don’t even wash our clothes with it, because the water attacks the colors and destroys the fabric.” She thus confirms many accounts of the matter. It was these that caused our contact in the region to voice his growing concerns to us.

We take in Rier our first sample of water on February 13th. It is of the water brought up by this hand pump. We then travel to Koch, which is 23 kilometers away from the refinery. Many of the people we talk to report that their livestock have died and that the water is bad. They are afraid of being called to account for such statements. For that reason, they refuse to tell us their names. “They made all sorts of promises to us: schools, road, supplies. And what have they delivered? Do you see any schools here? What we need is healthful land and clean water, so that we can let our herds graze,” says a young man.

We subsequently have a meeting with Colonel Peter Bol Ruot, the Commissioner of the county of Koch. He is holding court in a nicely-furnished and extended tukul. His “court” is strangely old-fashioned. The hut is very clean and neat. An acacia occupies the center of the yard, providing shade. We are offered places to sit—on plastic chairs bleached by the sun. The chair of the lord of the manor has been placed behind a small table. A satellite telephone lies on it. This is the status symbol in this remote region. We feel like we are being received by royalty.

The Commissioner answers our questions in a friendly way. His answers are alarming. In 2006, he states, 27 adults and 3 children died from drinking water contaminated with chemicals. At this moment, up to 1,000 persons have fallen sick due to the water, which has also killed large numbers of livestock. The Commissioner reports having gathered the local residents’ complaints and having relayed them to the oil consortium which is the licensee for Block 5A—the local oil field. In three cases, indemnification was paid—“without recognition of culpability on the part of the operator”, in the words of another official representative when speaking to the “AFP”. No other amends were made, the large number of cases notwithstanding.

Shortly after the meeting with the Commissioner, we encounter a man39 who works for one of the oil companies. He speaks openly about staff members’ wearing of gloves and face masks while they go about tossing chemical wastes into pits that have been dug for that purpose. As the man says, it’s now the dry season. In the rainy one to follow, these pits will be flooded. We take samples of the water in the wells in Koch and in that of the marshes along the road from Koch to Thar Jath, which goes around the refinery. We also do the same in the wells found in the town of Mirmir and in the swamp there. The least distance between the places of sampling and the suspected source of the contamination—the refinery—is 600 meters; the greatest, 32.7 kilometers.

Читать дальше