Oil, power and a Sign of Hope

Of corporations and the

human right to clean water

Klaus Stieglitzwith Sabine Pamperrien

Translated byTerry Swartzberg

This book is dedicated to the people in South Sudan whose great suffering is due to the activities of the oil industry, and, in the final analysis, to our hunger for energy.

First edition Spring 2016

All rights reserved

Copyright © 2016 by rüffer & rub Sachbuchverlag GmbH, Zürich

info@ruefferundrub.ch| www.ruefferundrub.ch

Printing and binding: CPI – Ebner & Spiegel, Ulm

Paper: Fly o5, special white, 90 g/m2, 1.2

E-Book: Clara Cendrós

ISBN 978-3-907625-96-5

ISBN e-book: 978-3-906304-02-1

Table of contents

Prologue — Powerless people

2008 — A suspicion

2009 — Questions for an oil consortium

2010 — Enter Daimler

2011 — Fact-checking

2012 — An elegant solution

2013 — The country recognizes the danger

2014 — Fighting for oil

2015 — The threat

Epilogue 2016 — Raising our voice

Appendix

Chronology of political events in Sudan

Abbreviations employed

Comments

Picture credits

Hoffnungszeichen | Sign of Hope e.V.

Our deepest thanks go to

Biographies

At the beginning of June 1994, Reimund Reubelt, staff member of Sign of Hope, traveled to Southern Sudan, which was being racked by a civil war in those days. He arrived in a small airplane. It was full of assistance supplies that Reimund had procured in Kenya. The airplane’s pilot was nervous. This was because he didn’t know — the rebels or the government’s forces — who controlled the airstrip at which they were going to land. He said: “If people start running at us, that’s a bad sign. We will have to immediately take off again.” The tall and haggard people waiting at the airfield approached the airplane in a slow and dignified pace.

The event, which took place more than 20 years ago, marked the beginning of Sign of Hope’s work in the country, in which more than 75 % of the people cannot read or write, and in which more than half live below the poverty level.

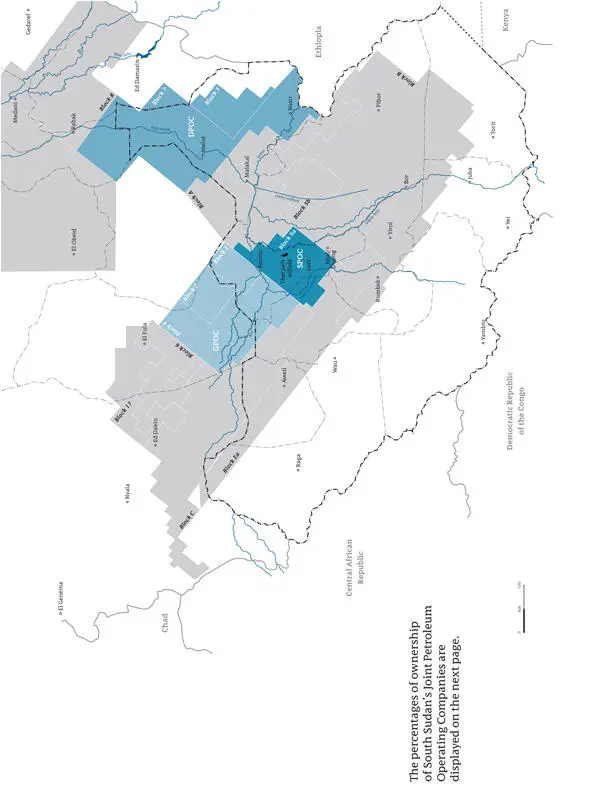

At the end of 2007, problems with drinking water were brought to the attention of Sign of Hope. The German organization was told of the contamination being found in the water available for drinking in certain regions of Southern Sudan. The initial tests made of the water confirmed the assumption that this contamination stemmed from the extraction of oil. Sign of Hope commissioned the conducting of a comprehensive, scientific study.

On March 5 th, the “AFP” publishes an article in English on the analyses of samples of hairs collected by Sign of Hope, and on their dramatic findings, and how they relate to South Sudan’s oil industry. This article is taken up and spread by international media.

And the story goes on.

PROLOGUE

Powerless people

July, 2012. Sarnico, a town in northern Italy. Throngs of paparazzi. George Clooney is shooting a commercial for a luxury version of Mercedes-Benz’s E-class of cars. The commercial covers the star’s determined attempts to get a close-up on the car. This entails him initially grabbing an aquaplane, which then follows a silver-colored model of the car as it winds its way down the spectacular road hugging the banks of the Lago d’Iseo. Clooney’s next step is to grab a speedboat, which flies him up close to the object of his desire. Great chase scene. The commercial’s message: the new model of Mercedes causes this womanizer to mobilize all of the well-known determination and charm that he normally displays when wooing an exquisitely attractive woman.

Clooney relaxes during the breaks between shooting by enjoying a bit of joshing with his fans, and by bringing food to the members of the crew. He lets himself be photographed while doing such. The world’s media snap up the photos.

Clooney makes an announcement during the day of shooting. He is going to auction off his 2008 Tesla Signature 100 Roadster, which has only 1,700 miles on its clock. And he is going to donate the proceeds to a project of assistance in Sudan.

August, 2012: $US 99,000. That’s the amount raised by the auctioning of Clooney’s four years old car. The funds go to the Satellite Sentinel Project, which Clooney helped found and which operates in Sudan.

*

It was sometime around 60 A.D. that the Emperor Nero decided to split off two of his centurions and their centuries (companies) from his legions stationed in Rome’s province of Egypt, and to send them south. The mission’s purpose was to scout the unknown lands stretching down to the sources of the White Nile, and to claim them for Rome, which would thus gain new, sub-Saharan lands. Nero was greedy for the gold supposed to be lying around for the picking in these lands, which comprised the ancient kingdom of Meroe. It was located in what is today’s Sudan. In the interests of maximizing his cost-benefits ratio, Nero gave his scouting party a clearly-defined mission: find out whether or not these unknown lands had any resources at all worthy of exploitation.

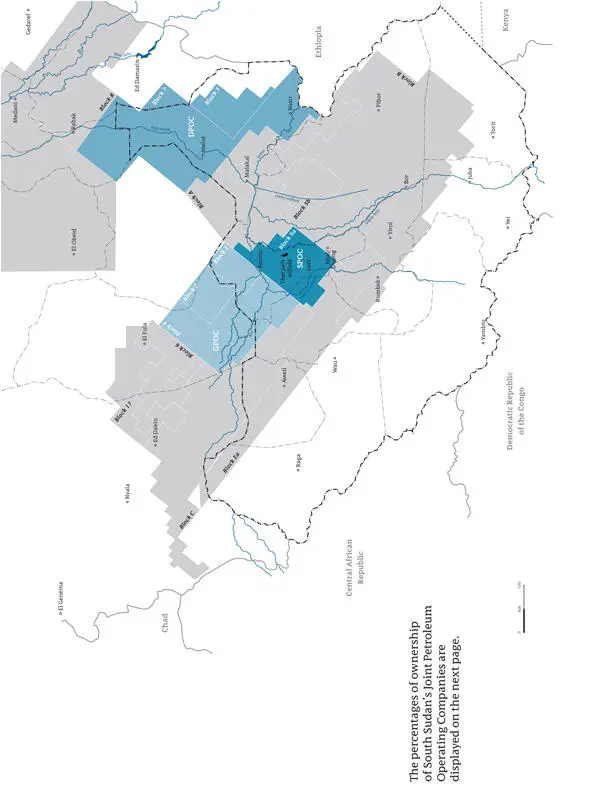

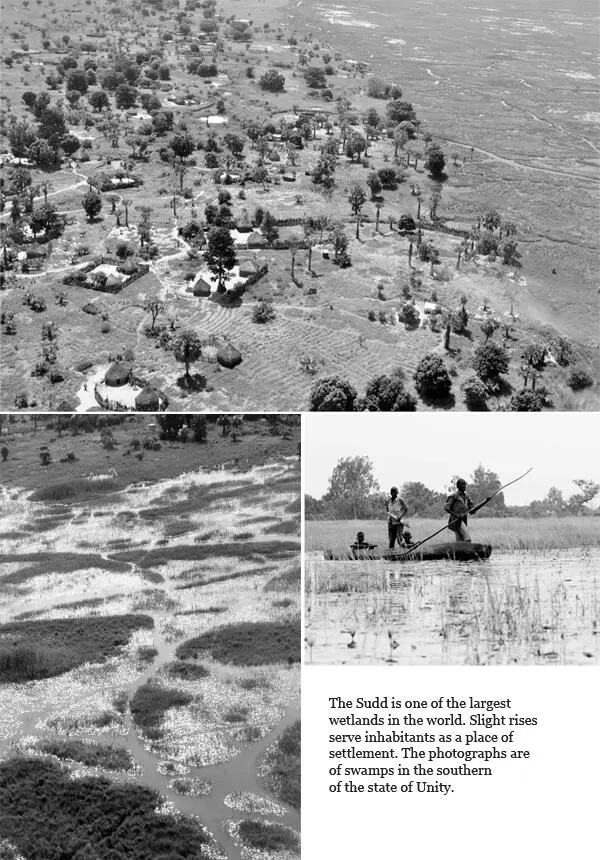

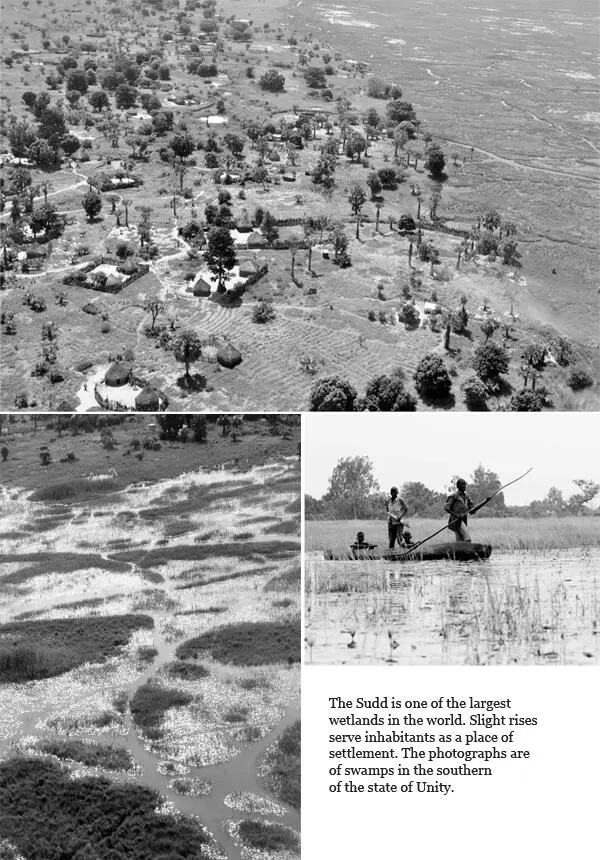

Overcoming and surviving unimaginably-challenging obstacles, the Roman legionnaires managed to reach Lake Victoria, the source of the White Nile. One of these obstacles was so challenging that it put an end to any visions of lasting conquest of the region: the “Sudd”. This gigantic, contiguous expanse of wetlands—nearly 6 million hectares in size—is located in Southern Sudan, and is one of the largest of its kind in the world. The Sudd is comprised of the White Nile’s countless arms and of the land between them. These streams are too shallow to be navigated by ships. The rest of the region is covered by such aquatic plants as papyrus and other reeds. These preclude any attempts at wading through it.

Seneca, the Roman historian, bequeathed us a telling description of the Sudd wetlands. It constitutes the first firmly documented mentioning of the region. “Sudd” stems from the Arabic “Sadet”, which means “barrier” or “dam”.

*

In May, 1847, Johannes von Müller, a researching botanist from southwestern Germany, embarked upon an expedition in Africa. He was accompanied by his secretary and trusty helper Alfred Brehm, who was the son of an ornithologist. The expedition started in Egypt. Its plan was to traverse the entire continent of Africa, and to research its fauna in the process. In January, 1848, von Müller and Brehm arrived in Sudan, which was under the control of the Ottoman Empire in those days. The Ottoman had expanded their sway over the Sudan from their base in Egypt ten years previously. Brehm made a copious amount of notes about and sketches of the people encountered in his travels. Brehm was especially moved and distressed by the slave trade, which was widespread in the Sudan of those days. Especially distressing to him was the exacting and unscrupulous treatment of the slaves by the Europeans living in the Sudan. During Brehm’s sojourn in the Sudan, he was witness to the arrival of slaves from a march that had started in the south of the region. The state of the dark-skinned humans, who were member of the Dinka ethnic group, especially bothered Brehm: “It was a ghastly sight, one that no words suffice to describe. It remained in my soul for weeks—as the epitome of horror. It took place on January 12, 1848.” 1As Brehm noted: “This fate of being regarded as objects of sale applies to all the ethnic groups of Abyssinia, including the Galla, Shewa, Makate, Amhara, […], the Shilluk, Dinka, Takhallaui, Darfuri, Sheibuni, Kik and Nuer.”2

Читать дальше