Differences between Cognitive and Emotional Biases

In this book, behavioral biases are classified as either cognitive or emotional biases, not only because the distinction is straightforward but also because the cognitive-emotional breakdown provides a useful framework for understanding how to effectively deal with them in practice. I recommend thinking about investment decision making as occurring along a (somewhat unrealistic) spectrum from the completely rational decision making of traditional finance to purely emotional decision making. In that context, cognitive biases are basic statistical, information processing, or memory errors that cause the decision to deviate from rationality. Emotional biases are those that arise spontaneously as a result of attitudes and feelings and that cause the decision to deviate from the rational decisions of traditional finance.

Cognitive errors, which stem from basic statistical, information processing, or memory errors, are more easily corrected for than are emotional biases. Why? Investors are better able to adapt their behaviors or modify their processes if the source of the bias is illogical reasoning, even if the investor does not fully understand the investment issues under consideration. For example, an individual may not understand the complex mathematical process used to create a correlation table of asset classes, but he can understand that the process he is using to create a portfolio of uncorrelated investments is best. In other situations, cognitive biases can be thought of as “blind spots” or distortions in the human mind. Cognitive biases do not result from emotional or intellectual predispositions toward certain judgments, but rather from subconscious mental procedures for processing information. In general, because cognitive errors stem from faulty reasoning, better information, education, and advice can often correct for them.

Difference among Cognitive Biases

In this book, we review 13 cognitive biases, their implications for financial decision making, and suggestions for correcting for the biases. As previously mentioned, cognitive errors are statistical, information processing, or memory errors—a somewhat broad description. An individual may be attempting to follow a rational decision-making process but fails to do so because of cognitive errors. For example, they may fail to update probabilities correctly, to properly weigh and consider information, or to gather information. If corrected by supplemental or educational information, an individual attempting to follow a rational decision-making process may be receptive to correcting the errors.

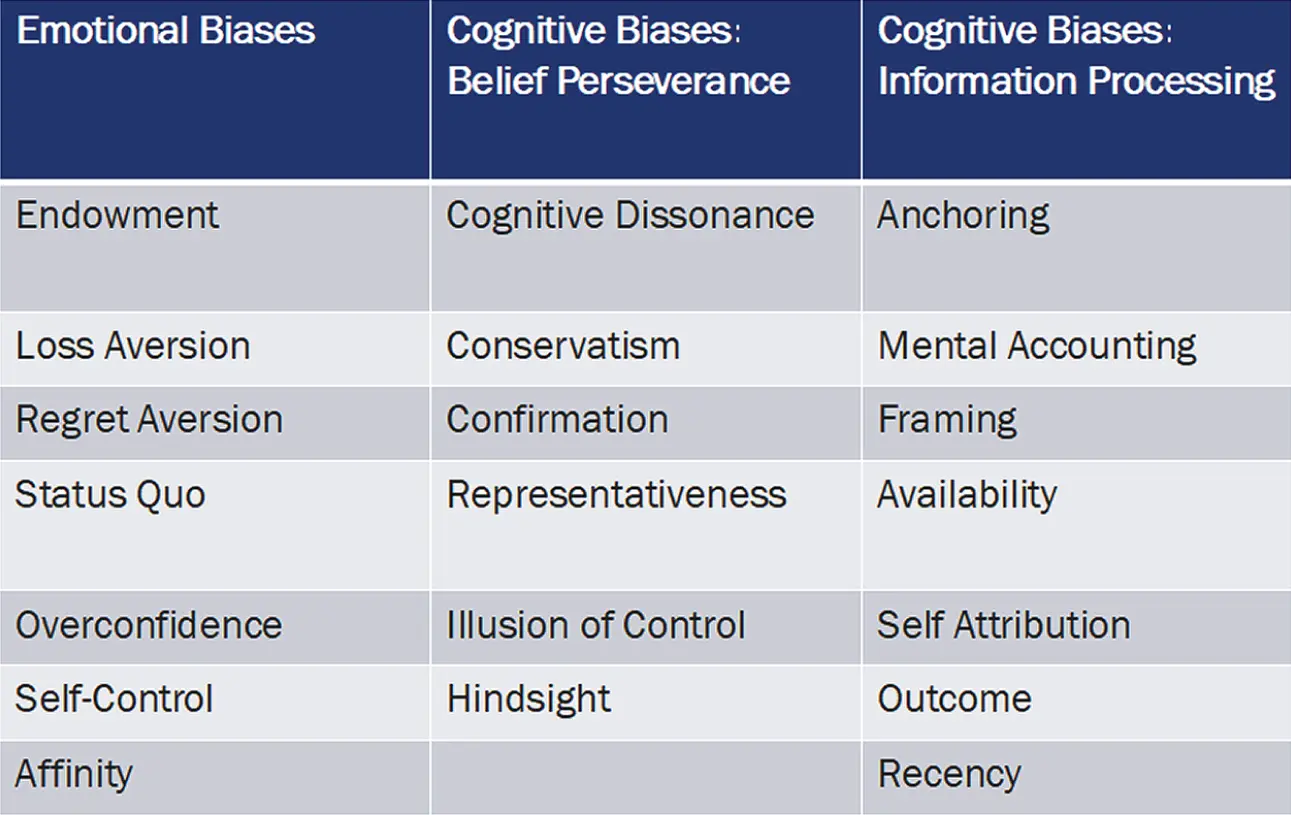

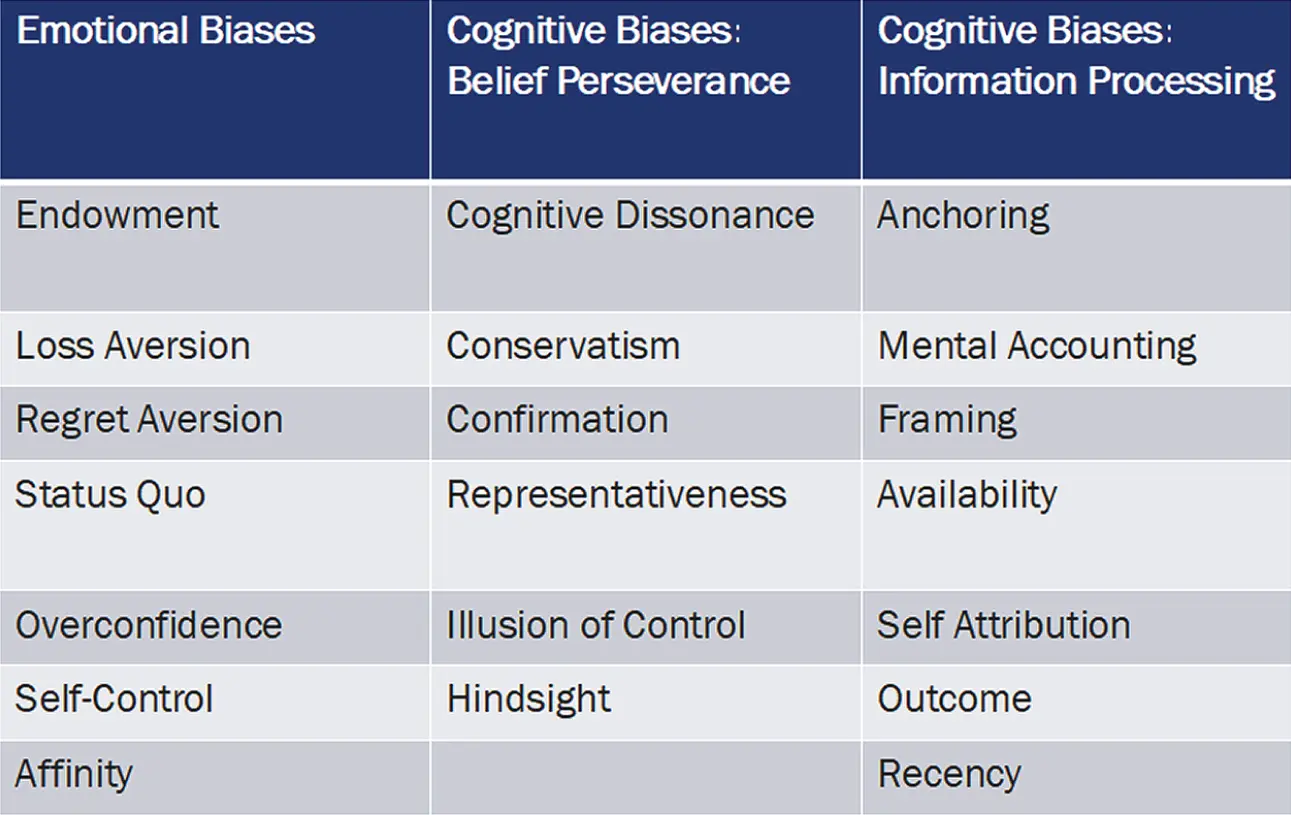

To make things simpler, I have identified and classified cognitive biases into two categories. The first category contains “belief perseverance” biases. In general, belief perseverance may be thought of as the tendency to cling to one's previously held beliefs irrationally or illogically. The belief continues to be held and justified by committing statistical, information processing, or memory errors.

Belief Perseverance Biases

Belief perseverance biases are closely related to the psychological concept of cognitive dissonance, a bias I will review in the next chapter. Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort that one feels when new information conflicts with previously held beliefs or cognitions. To resolve this discomfort, people tend to notice only information of interest to them (called selective exposure), ignore or modify information that conflicts with existing beliefs (called selective perception), and/or remember and consider only information that confirms existing beliefs (called selective retention). Aspects of these behaviors are contained in the biases categorized as belief perseverance. The six belief perseverance biases covered in this book are: cognitive dissonance, conservatism, confirmation, representativeness, illusion of control, and hindsight.

Information-Processing Biases

The second category of cognitive biases has to do with “processing errors,” and describes how information may be processed and used illogically or irrationally in financial decision making. As opposed to belief perseverance biases, these are less related to errors of memory or in assigning and updating probabilities and instead have more to do with how information is processed. The seven processing errors discussed are: anchoring and adjustment, mental accounting, framing, availability, self-attribution bias, outcome bias, and recency bias.

Individuals are less likely to make cognitive errors if they remain vigilant to the possibility that they may occur. A systematic process to describe problems and objectives; to gather, record, and synthesize information; to document decisions and the reasoning behind them; and to compare the actual outcomes with expected results will help reduce cognitive errors.

Although emotion has no single universally accepted definition, it is generally agreed upon that an emotion is a mental state that arises spontaneously rather than through conscious effort. Emotions are related to feelings, perceptions, or beliefs about elements, objects, or relations between them; these can be a function of reality or the imagination. Emotions may result in physical manifestations, often involuntary. Emotions can cause investors to make suboptimal decisions. Emotions may be unwanted by the individuals feeling them, and while they may wish to control the emotion and their response to it, they often cannot.

Emotional biases are harder to correct for than cognitive errors because they originate from impulse or intuition rather than conscious calculations. In other words, a bias that is an inclination of temperament or outlook, especially a personal and sometimes unreasonable judgment, is harder to correct. When investors adapt to a bias, they accept it and make decisions that recognize and adjust for it rather than making an attempt to reduce it. To moderate the impact of a bias is to recognize it and to attempt to reduce or even eliminate it within the individual rather than to accept the bias. In the case of emotional biases, it may be possible to only recognize the bias and adapt to it rather than correct for it.

Emotional biases stem from impulse, intuition, and feelings and may result in personal and unreasoned decisions. When possible, focusing on cognitive aspects of the biases may be more effective than trying to alter an emotional response. Also, educating the investors about the investment decision-making process and portfolio theory can be helpful in moving the decision making from an emotional basis to a cognitive basis. When biases are emotional in nature, drawing them to the attention of the individual making the decision is unlikely to lead to positive outcomes. The individual is likely to become defensive rather than receptive to considering alternatives. Thinking of the appropriate questions to ask and to focus on as well as potentially altering the decision-making process are likely to be the most effective options.

Emotional biases can cause investors to make suboptimal decisions. The emotional biases are rarely identified and recorded in the decision-making process because they have to do with how people feel rather than what and how they think. The six emotional biases discussed are: loss aversion, overconfidence, self-control, status quo, endowment, and regret aversion. In the discussion of each of these biases, some related biases may be discussed.

Figure 2.2 Categorization of Twenty Behavioral Biases

Читать дальше