Two days later Napoleon, still at Albenga, reports that he has found Royalist traitors in the army, and complains that the Treasury had not sent the promised pay for the men, "but in spite of all, we shall advance." Massena, eleven years older than his new commander-in-chief, had received him coldly, but soon became his right-hand man, always genial, and full of good ideas. Massena's men are ill with too much salt meat, they have hardly any shoes, but, as in 1800, 42he has never a doubt that Bonaparte will make a good campaign, and determines to loyally support him. Poor Laharpe, so soon to die, is a man of a different stamp—one of those, doubtless, of whom Bonaparte thinks when he writes to Josephine, "Men worry me." The Swiss, in fact, was a chronic grumbler, but a first-rate fighting man, even when his men were using their last cartridges.

" The lovers of nineteen. "—The allusion is lost. Aubenas, who reproduces two or three of these letters, makes a comment to this sentence, "Nous n'avons pu trouver un nom à mettre sous cette fantasque imagination" (vol. i. 317).

" My brother ," viz. Joseph.—He and Junot reached Paris in five days, and had a great ovation. Carnot, at a dinner-party, showed Napoleon's portrait next to his heart, because "I foresee he will be the saviour of France, and I wish him to know that he has at the Directory only admirers and friends."

No. 6.

Unalterably good. —"C'est Joseph peint d'un seul trait."—Aubenas (vol. i. 320).

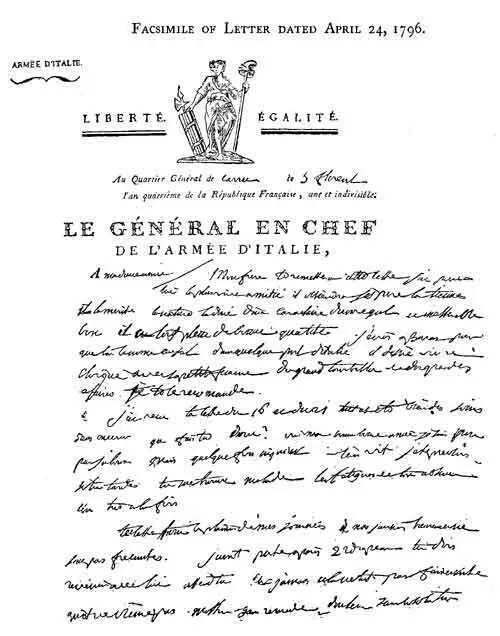

" If you want a place for any one, you can send him here. I will give him one. "—Bonaparte was beginning to feel firm in the saddle, while at Paris Josephine was treated like a princess. Under date April 25th, Letourneur, as one of the Directory, writes him, "A vast career opens itself before you; the Directory has measured the whole extent of it." They little knew! The letter concludes by expressing confidence that their general will never be reproached with the shameful repose of Capua. In a further letter, bearing the same date, Letourneur insists on a full and accurate account of the battles being sent, as they will be necessary "for the history of the triumphs of the Republic." In a private letter to the Directory (No. 220, vol. i. of the Correspondence , 1858), dated Carru, April 24th, Bonaparte tells them that when he returns to camp, worn-out, he has to work all night to put matters straight, and repress pillage. "Soldiery without bread work themselves into an excess of frenzy which makes one blush to be a man." 43... "I intend to make terrible examples. I shall restore order, or cease to command these brigands. The campaign is not yet decided. The enemy is desperate, numerous, and fights well. He knows I am in want of everything, and trusts entirely to time; but I trust entirely to the good genius of the Republic, to the bravery of the soldiers, to the harmony of the officers, and even to the confidence they repose in me."

No. 7.

Aubenas goes into ecstasies over this letter, "the longest, most eloquent, and most impassioned of the whole series" (vol. i. 322).

Facsimile of Letter dated April 24, 1796.

June 15. —Here occurs the first gap in the correspondence, but his letters to the Directory between this date and the last letter to Josephine extant (April 24) are full of interest, including his conscientious disobedience at Cherasco, and the aura of his destiny to "ride the whirlwind and direct the storm" which first inspired him after Lodi. On April 28th was signed the armistice of Cherasco, by which his rear was secured by three strong fortresses. 44He writes the Directory that Piedmont is at their mercy, and that in making the armistice into a definite peace he trusts they will not forget the little island of Saint-Pierre, which will be more useful in the future than Corsica and Sardinia combined. He looks upon northern Italy as practically conquered, and speaks of invading Bavaria through the Tyrol. "Prodigious" is practically the verdict of the Directory, and later of Jomini. "My columns are marching; Beaulieu flees. I hope to catch him. I shall impose a contribution of some millions on the Duke of Parma: he will sue for peace: don't be in a hurry, so that I may have time to make him also contribute to the cost of the campaign, by replenishing our stores and rehorsing our waggons at his expense." Bonaparte suggests that Genoa should pay fifteen millions indemnity for the frigates and vessels taken in the port. Certain risks had to be run in invading Lombardy, owing to want of horse artillery, but at Cherasco he secured artillery and horses. When writing to the Directory for a dozen companies, he tells them not to entrust the execution of this measure "to the men of the bureaus, for it takes them ten days to forward an order." Writing to Carnot on the same day he states he is marching against Beaulieu, who has 26,000 foot out of 38,000 at commencement of campaign. Napoleon's force is 28,000, but he has less cavalry. On May 1st, in a letter dated Acqui to Citizen Faipoult, he asks for particulars of the pictures, statues, &c., of Milan, Parma, Placentia, Modena, and Bologna. On the same day Massena writes that his men are needing shoes. On May 6th Bonaparte announces the capture of Tortona, "a very fine fortress, which cost the King of Sardinia over fifteen millions," while Cherasco has furnished him with twenty-eight guns. Meanwhile Massena has taken possession of Alessandria, with all its stores. On May 9th Napoleon writes to Carnot, "We have at last crossed the Po. The second campaign is begun; Beaulieu ... has fool-hardiness but no genius. One more victory, and Italy is ours." A clever commissary-general is all he needs, and his men are growing fat—with good meat and good wine. He sends to Paris twenty old masters, with fine examples of Correggio and Michael-Angelo. It is pleasant to find Napoleon's confidence in Carnot, in view of Barras' insinuations that the latter had cared only for Moreau—his type of Xenophon. In this very letter Napoleon writes Carnot, "I owe you my special thanks for the care that you have kindly given to my wife; I recommend her to you, she is a sincere patriot, and I love her to distraction." He is sending "a dozen millions" to France, and hopes that some of it will be useful to the army of the Rhine. Meanwhile, and two days before Napoleon's letter to Carnot just mentioned, the latter, on behalf of the Directory, suggests the division of his command with the old Alsatian General Kellermann. The Directory's idea of a gilded pill seems to be a prodigiously long letter. It is one of those heart-breaking effusions that, even to this day, emanate from board-rooms, to the dismay and disgust of their recipients. After plastering him with sickening sophistries as to his "sweetest recompense," it gives the utterly unnecessary monition, "March! no fatal repose, there are still laurels to gather"! Nevertheless, his plan of ending the war by an advance through the Tyrol strikes them as too risky. He is to conquer the Milanais, and then divide his army with Kellermann, who is to guard the conquered province, while he goes south to Naples and Rome. As an implied excuse for not sending adequate reinforcements, Carnot adds, "The exaggerated rumours that you have skilfully disseminated as to the numbers of the French troops in Italy, will augment the fear of our enemies and almost double your means of action." The Milanais is to be heavily mulcted, but he is to be prudent. If Rome makes advances, his first demand should be that the Pope may order immediate public prayers for the prosperity and success of the French Republic! The sending of old masters to France to adorn her National Galleries seems to have been entirely a conception of Napoleon's. He has given sufficiently good reasons, from a patriotic point of view; for money is soon spent, but a masterpiece may encourage Art among his countrymen a generation later. The plunderers of the Parthenon of 1800 could not henceforward throw stones at him in this respect. But his real object was to win the people of Paris by thus sending them Glory personified in unique works of genius.

Читать дальше