4.2.3 Identifying and Screening Potentially Eligible Trials

Identification of eligible trials should be based on a systematic and comprehensive search of a number of sources, to ensure that all relevant trials are identified, using the same or similar methods to those employed in a conventional systematic review of existing aggregate data. 92However, IPD meta‐analysis projects often have a greater emphasis on searching grey literature sources, such as conference proceedings, as well as trial registers to identify unpublished trials, and any ongoing trials that may complete in time for inclusion in the IPD meta‐analysis. 7,9,43For example, in an IPD meta‐analysis project examining the effects of chemoradiation for cervical cancer, 93about 25% of the included trials were unpublished or published only as an abstract. Although there may be initial concerns about the quality of unpublished trials, this can be formally evaluated ( Sections 4.5and 4.6), and having the accompanying protocol, case report forms and trial IPD enables more detailed quality checking than when relying on aggregate data reported in publications. Indeed, a high standard of reporting does not necessarily correspond to high‐quality trial design and conduct, and similarly, some good‐quality trials can be quite badly reported.

Trial investigators should be asked whether they can supplement the provisional list of eligible trials, and additional appeals might also be made via project websites, social media or conference presentations. A summary of the sources searched for an IPD meta‐analysis of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 for spinal fusion is given in Box 4.2.

Box 4.2Summary of the sources searched for an IPD meta‐analysis of randomised trials examining recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 for spinal fusion.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

MEDLINE 1948 to present

EMBASE 1974 to present

Science Citation Index 1899 to present

Automated “current awareness” searches to June 2012

ClinicalTrials.gov (to identify ongoing or unpublished randomised trials)

Published a call for evidence

Source: Lesley Stewart, listing the sources used by Simmonds et al., 65with permission.

The screening process for deciding which trials are relevant for inclusion is very similar to that for standard systematic reviews. 92However, with IPD meta‐analysis projects, because there is usually greater contact with trial investigators, any doubt as to the eligibility of a particular trial (e.g. in relation to whether particular variables or outcomes are recorded in the trial’s IPD) can be clarified through discussion. This process should be well documented, so that it can be used to help populate a PRISMA‐IPD flow diagram ( Chapter 10). 60

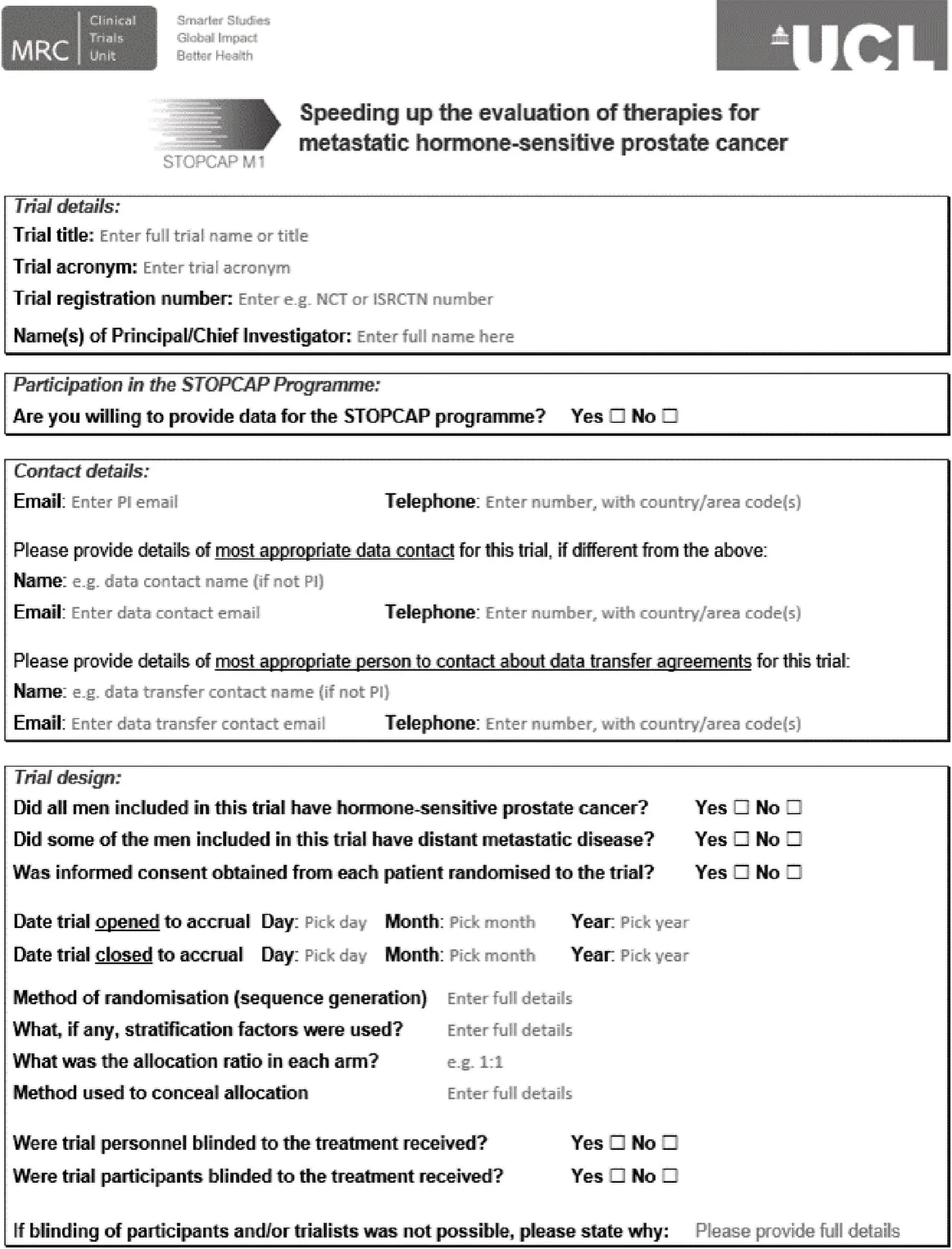

4.2.4 Deciding Which Information Is Needed to Summarise Trial Characteristics

After relevant trials are identified, it is important to obtain a good understanding of the attributes and characteristics of these trials, for descriptive purposes. This may include contacting trial investigators to request extra information about the trial population and treatment and control interventions. In addition, gathering structured trial‐level information about the methods of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, planned and actual recruitment, and any stopping rules that were applied can be valuable when assessing risk of bias ( Section 4.6), particularly if these aspects are not clearly reported in trial publications. 48This may be particularly pertinent for older trials with limited documentation.

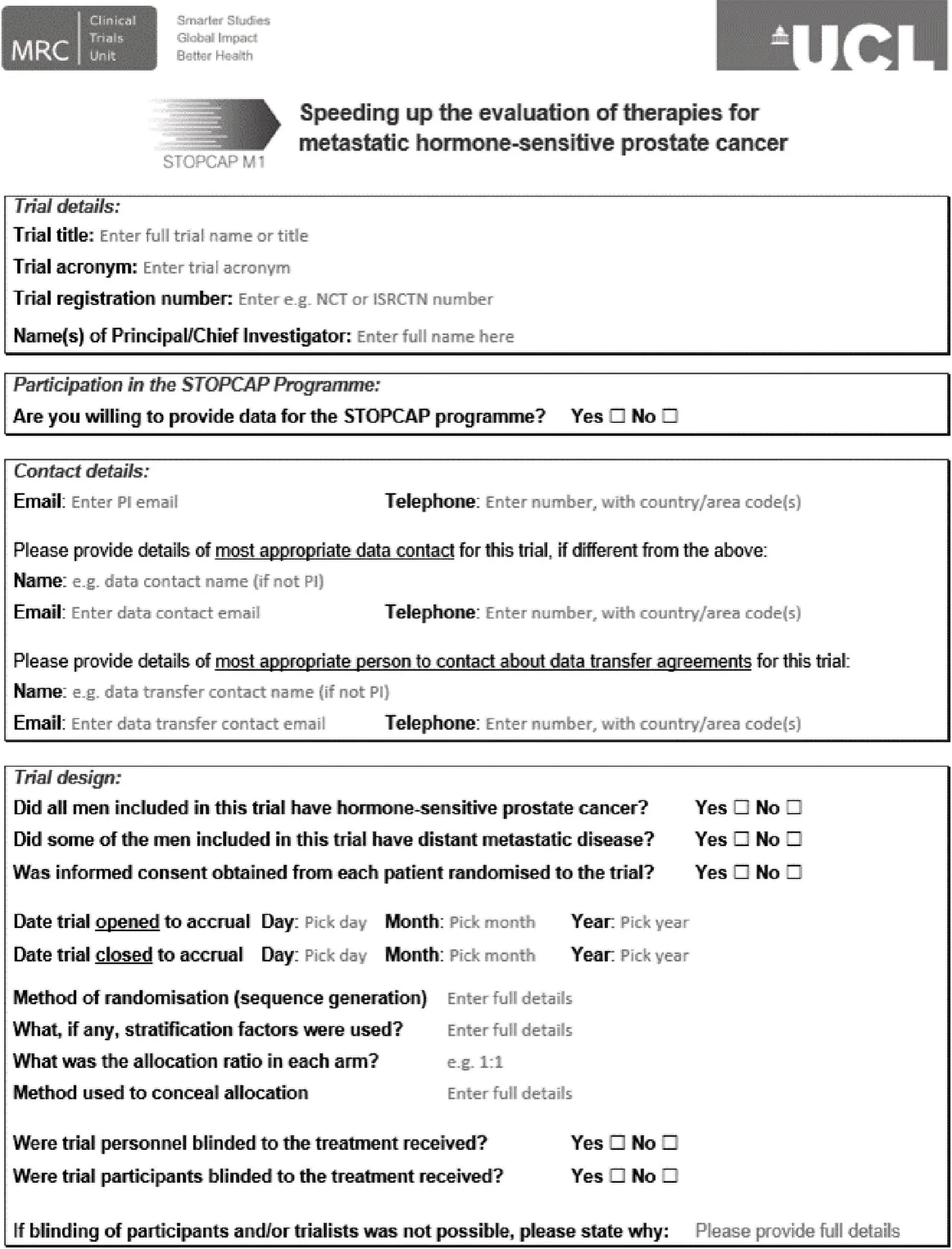

As there may be a considerable amount of information to collect, it is helpful to use a pre‐prepared paper or online data collection form, which may be included as an appendix in the project protocol and accompany the invitation to collaborate. An example is shown in Figure 4.3.

This form is also useful for seeking administrative details for each trial, such as the trial identifier and/or acronym, the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) number (if relevant), trial title and up‐to‐date trial publication information. Also, it is worth including a question about whether the principal trial investigator will be the key contact for the IPD meta‐analysis project, or whether another individual, such as the trial statistician or data manager, will be responsible (providing space for their contact details). This would also be the place to ask trial investigators if they are aware of any potentially eligible trials not currently included in the draft protocol.

4.2.5 Deciding How Much IPD Are Needed

The searching and screening process will have produced a set of potentially eligible trials. This may have been refined by seeking early clarifications about trial characteristics, and possibly also by setting an information size threshold (e.g. based on contribution toward power; see Chapter 12), or a quality threshold (e.g. based on an initial risk of bias examination based on published information; see Section 4.2.1), which trials must pass in order to be included. Further clarification and consideration of these issues may be required when more detailed engagement with trial investigators begins, and the likely shape and size of the available IPD emerges.

Figure 4.3Excerpt from a trial‐level data collection form for the STOPCAP M1 programme of IPD meta‐analyses of therapies for metastatic prostate cancer. 94

Source: Based on Tierney JF, Vale CL, Parelukar WR, et al. Evidence Synthesis to Accelerate and Improve the Evaluation of Therapies for Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Focus 2019;5(2):137–43.

Given this set of eligible trials, how much IPD should be sought from them? As a general rule, the aim should be to maximise the quantity and quality of IPD available, in order to fulfil the project objectives and complete the planned analyses reliably. For conventional reviews, aggregate data would ordinarily be sought for all studies relevant to the question of interest. Similarly, and ideally, IPD should be sought from all the eligible trials, for all participants recruited to those trials, and for all relevant outcomes, even if they were not published or included in the original analyses. This will help circumvent the risk of publication bias, outcome reporting bias, attrition bias, and other data availability biases ( Chapter 9). 46.58,95For example, in trials of the effectiveness of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 for spinal fusion, the adverse event data were not reported sufficiently to allow a rigorous evaluation of safety, 96whereas the collection of IPD allowed a complete, detailed, and in‐depth analysis. 65If it is not feasible or practical to seek IPD from all trials, the potential impact of these ‘missing’ trials should be taken into account ( Chapter 9).

4.2.6 Deciding Which Variables Are Needed in the IPD

As for all systematic reviews, the pre‐specified outcomes for the IPD meta‐analysis project should be those judged to be most important and relevant to the objectives, even if ultimately there are insufficient data available to analyse all of them. While consideration of the participant‐level variables required begins when the IPD meta‐analysis questions are formulated, this should be re‐visited before requesting IPD from trial investigators, so that they can be specified more precisely and ensure that the planned analyses can be completed satisfactorily. Trial publications can provide an initial guide as to which data might be available, but more variables may have been collected in a trial than is evident from a trial report. Often the trial protocol and the associated case report forms can provide a more reliable indication of which data have been recorded. Irrespective of whether these documents are available or not, it is useful to supply trial investigators with a provisional list of desired variables via a paper or online form, or as a detailed data dictionary ( Section 4.2.7), so that trial teams can clarify precisely which data items they can provide. An example of the typical types of data requested from trial investigators is shown in Box 4.3.

Читать дальше