The neo-liberal commitment to free trade was premised on the belief that market-based trade relations would promote growth much more effectively than controls introduced by governments on trade with other countries. This commitment to free trade and ‘open borders’ was complemented by the withdrawal of government support for ‘Industrial Policy’ (a term loosely used to describe policies directed at all activities in the productive sector). Government support for industry – ‘picking winners’ (promoting particular sectors and ‘national champion’ firms) – and financial support for innovation and other determinants of long-term growth were seen as raising the tax burden and reducing the efficiency of resource allocation, and thus being harmful to economic growth.

The consequence of this dual neo-liberal policy agenda was a hollowing-out of manufacturing in those high-income countries pursuing the neo-liberal agenda most vigorously, particularly the US and the UK. It resulted in the growth of high levels of unemployment in the rust-belt regions which had formerly been centres of industrial activity, for example in cities such as Michigan in the US Midwest, and Birmingham and Sunderland in the Midlands and the North-East in the UK. (I will discuss the social and political consequences of this deindustrialization in the next chapter.) It also led to a shift in the geography of investment by many of the major global corporations. There was a massive outflow of investment from the home economy and other high-income economies to economies in the developing world, particularly China. Much of this investment was directed to shifting supply chains to low-wage developing economies. The share of global direct foreign investment directed to developing economies rose from 17 per cent in 1990 to 44 per cent in 2019. 1

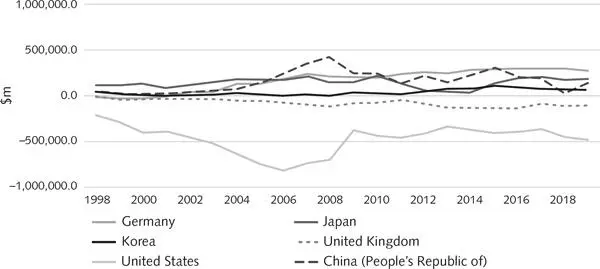

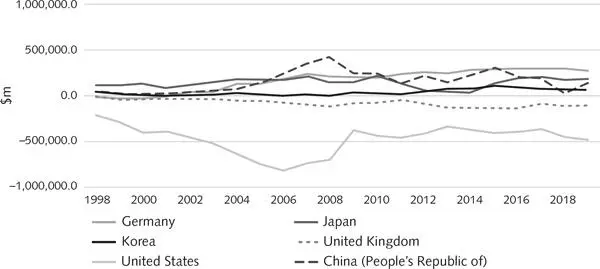

These developments resulted in the growth of trade imbalances between economies. That is, they consistently imported more from other countries than they exported. The level of this deficit was particularly high for the world’s largest economy, the US, and for the UK ( Figure 2.4). By contrast, countries such as China, Korea and Germany, which had pursued dirigiste policies to support industry, had growing trade surpluses, accompanied by relatively high rates of economic growth.

Figure 2.4 Balance of payments: largest debtor and surplus economies, 1998–2019 ($m)

Source : data from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

This toxic combination of deindustrialization and free trade undermined the incentive to invest and reduced the rate of productivity and economic growth in the economies pursuing neo-liberal policy agendas. But, as we will see in the following chapter, it also contributed to growing inequality, the precarity of livelihoods and the rise of populist political leaders.

The crisis in macroeconomic policy – matching demand with supply

Building factories and infrastructure requires a variety of inputs, including labour, material supplies and services. The production of these inputs generates incomes. Workers earn wages and salaries, and this cascades along the supply chain as suppliers require their own suppliers. But does this economic activity add up to the balancing of supply and demand? Are the incomes generated in all of the supply chains sufficient to consume what is being produced in the economy?

‘Say’s Law’ in economic theory posits that supply (investment and production) creates an equivalent level of demand (incomes and consumption). In other words, the making of things produces the incomes required to consume what is made. Thus, it is believed, one problem which should not concern policy makers is the need to help consumers to mop up all the goods and services which the economy can produce. However, history shows that this key tenet in economic theory is fallacious. At its core, capitalism has consistently experienced periods in which demand is unable to keep up with productive capacity. This is not surprising. New technologies produce more products with less labour. Thus, unless wage growth or consumption by the owners of productive capital outstrip productivity growth, it stands to reason that the incomes generated in production will not be sufficient to consume the products churned out by new, more efficient production lines. Moreover, in periods when consumer confidence is low, consumers may prefer to hold back, to save their incomes for a rainy day.

Both of these factors were at play during the Great Depression in the 1930s. The Great Crash in the stock markets in 1929 plunged many consumers into debt. Unemployment grew rapidly, partly – as we will see in Chapter 5– as a result of the introduction of labour-saving mass production technologies. And consumer confidence plummeted. Moreover, income inequality had grown rapidly during the 1920s and there were limits to how many luxury yachts, gold-plated watches and designer clothes an individual could consume. The combination of these developments resulted in a downward spiral in the major economies. As consumption fell, firms reduced their output or went out of business. This led to a reduction in the incomes required to consume what was being produced. Consumer confidence fell, further dampening the demand for the goods. And thus, the economy spiralled downwards.

These problems, and the resultant policy responses, were addressed by Keynes during the 1930s. He argued that, since there was a periodic tendency in capitalism towards under-consumption, public policy had to intervene to support demand. Tackling the crisis in confidence during his inauguration in 1932, President Roosevelt famously declared, ‘The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.’ He then rolled out his New Deal Program which increased government expenditure and helped to grow the US economy out of its deep depression. The New Deal provided relief to the unemployed. It created 250,000 jobs for young men to work in projects in rural areas, and promoted very large investments in infrastructure, skills development, schools and other public facilities. Although in itself the New Deal did not solve the problem of economic stagnation (it was the ‘boom’ created by the mass production of arms during World War 2 which proved to be the decisive stimulant to growth), these government-led investment programmes played an important role in economic revival.

The challenge of managing consumption to balance production remained a critically important component of public and economic policy throughout the twentieth century, and has endured during the first two decades of the twenty-first century. As we will see in subsequent chapters, after World War 2, government expenditure played an important role in sustaining consumer demand. In the US, and then in Europe, there were massive investments in housing and in the infrastructure required to promote the growth of automobilization and suburbanization. In Europe, welfare programmes played a complementary role in sustaining consumption. Although these post-war welfare programmes were not rationalized in terms of their contribution to economic stability and growth, both directly (though benefit payments) and indirectly (as jobs were created in the public sector delivering welfare benefits) they played a critical role in bolstering consumption.

But from the beginning of the 1980s, these well-tried structures for matching demand and supply in the economy were undermined by the introduction of neo-liberal economic policies. These were pioneered in the UK and the US – the Thatcher–Reagan revolution – and then replicated across the globe, sometimes as a result of national choice and, in other cases (notably in the developing world), as a result of pressure exerted by the US, the UK and the EU. Neo-liberalism sought to reduce the role of government and to reduce the ‘tax burden’. It promoted lower tax rates on higher incomes in order to ‘remove the disincentive to entrepreneurship and investment’. Simultaneously, the neo-liberal agenda attacked welfare payments on the basis that social security promoted the growth of a ‘work-shy’ labour force living off welfare. (The irony in this agenda was that, whilst it was argued that welfare support reduced the incentive of the poor to work, it was simultaneously argued that tax reduction would increase the incentive of the rich to work even harder!)

Читать дальше