Zaher Al Taqi, BDS, MDSPrivate practice Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Antonis Chaniotis, DDS, MDSPrivate practice limited to Microscopic Endodontics Athens, Greece

Gergely Benyőcs, DDS, MDSPrivate practice limited to Microscopic Endodontics Budapest, Hungary

Eugen Buga, DDS, MDSPrivate practice limited to Microscopic Endodontics Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

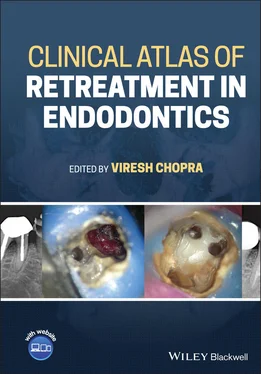

Viresh Chopra, BDS, MDSSenior Lecturer, Adult Restorative Dentistry, Course Leader, Endodontology Oman Dental College Muscat, Oman

Fugen Dagli Comert, DDS, PhDProfessor, Adult Restorative Dentistry, and Specialist Endodontist Oman Dental College Muscat, Oman

Mohammad Hammo, BDS, DESEChairman of British Academy of Implants and Restorative Dentistry Private practice limited to Endodontics Jordan and Bahrain

Padmanabh Jha, BDS, MDSProfessor, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics Subharti Dental College, Swami Vivekanand Subharti University Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India

Bekir Karabucak, DMD, MSChair and Professor of Endodontics, Director of Postgraduate Endodontic Program, and Director of Advanced Dental Education School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA, USA

Meetu Ralli Kohli, BDS, DMDClinical Associate Professor of Endodontics, Department of Endodontics School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA, USA

Jojo Kottoor, BDS, MDSPrivate practice limited at Root Canal Point Kerala, India

Sanjay Miglani, MDS, FISDRProfessor, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia Millia Islamia University New Delhi, India

Swadheena Patro, BDS, MDSProfessor, Department of Endodontics Kalinga Institue of Dental Sciences Patia, Bhubaneswar, India

Garima Poddar, BDSSenior Consultant, Dental Department Shanti Memorial Hospital Pvt. Ltd. Cuttack, Odisha, India Faculty Diploma in endodontic program, Universitat Jaume I (UJI), Castelló, Spain

MTA – Mineral Trioxide Aggregate

PDL – Periodontal ligament

IOPAR – Intraoral periapical radiograph

IANB – Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block

NaOCl – Sodium Hypochlorite

EDTA – Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

GP – Gutta Percha

CBCT – Cone beam computed tomography

PUI – Passive ultrasonic irrigation

About the Companion Website

This book is accompanied by a companion website:

https://www.wiley.com/go/chopra/retreatment

The website include:

Videos

Introduction to endodontic retreatment

Sanjay Miglani, Fugen Dagli Comert, Swadheena Patro, and Viresh Chopra

There has been massive growth in endodontic treatment in recent years. The main aim of root canal treatment is to disinfect and shape the root canal system and seal it in three dimensions to prevent reinfection of the tooth [1, 2]. Although initial root canal therapy is known to be a predictable procedure with a high degree of success [3–6], failures can occur after treatment.

Literature has reported failure rates of 14–16% for initial root canal treatment [3, 7]. Lack of healing is due to persistent intraradicular infection residing in previously uninstrumented canals, dentinal tubules or in the complex irregularities of the root canal system [8–11]. The extraradicular causes of endodontic failures include periapical actinomycosis [12], a foreign body reaction due to extruded endodontic materials [13, 14], an accumulation of endogenous cholesterol crystals in the apical tissues [15] and an unresolved cystic lesion [16, 17].

The term ‘retreatment’ is widely used in endodontics to denote a new intervention aimed at retaining the tooth in the oral cavity [18]. Previously treated teeth with persistent periapical lesion(s) might be preserved with non‐surgical retreatment or endodontic surgery, assuming the tooth is restorable and periodontally sound, and the patient wants to retain the tooth. When a decision is made to preserve the tooth, the clinician and patient face the challenge of selecting the treatment with the most beneficial long‐term outcome.

Evidence‐based dentistry recommends selection of alternative treatment options based on the best available evidence [19]. Intuitively, a considered medical procedure is regarded as meaningful only if it is thought to bring about some benefit to the patient. Accordingly, the consequences of treating or not treating the disease in question must be at the core of the clinical decision‐making process.

According to the Glossary of Endodontic Terms of the American Association of Endodontists, retreatment [20] is defined as:

A procedure to remove root canal filling materials from the tooth, followed by cleaning, shaping and obturation of the root canals.

The indications for ‘root canal retreatment’ given by the European Society of Endodontology [21] are:

teeth with inadequate root canal filling with radiological findings of developing persisting apical periodontitis (apical lesion)

teeth with inadequate root canal filling when the coronal restoration requires replacement or the coronal dental tissue is to be bleached.

The above definitions, though correct, describe only one clinical situation of reintervention – when there is need to remove the previous root canal filling material.

Carr [22] proposed an updated and comprehensive definition of reintervention:

Endodontic retreatment is a procedure performed on a tooth that underwent a previous attempt at definitive treatment resulting in a condition that requires further endodontic intervention to achieve a successful outcome.

I.2 Rationale for retreatment

Root canal system anatomy plays a significant role in endodontic success and failure [23–25]. It contains branches that communicate with the periodontal attachment apparatus furcally and laterally, and often terminate apically into multiple portals of exit [26]. Therefore, any opening from the root canal system (RCS) to the periodontal ligament space should be thought of as a portal of exit (POE) through which potential endodontic breakdown products may pass [27, 28].

There can be various causes for endodontic failures such as:

missed canals

pathological or iatrogenic perforations

inadequate obturations

inadequacies in shaping, cleaning and obturation, iatrogenic events, or reinfection of the RCS when the coronal seal is lost after completion of root canal treatment [29–32].

Regardless of all the causative factors, the final cause for failure is leakage and bacterial contamination due to inadequate debridement, disinfection or sealing of the RCS.

Success can be achieved in previously failed endodontic cases by confirming the restorability of the tooth in question, careful treatment planning and proper execution of the treatment plan. In addition, it depends upon the skill of the individual operator performing the procedure.

I.3 Aim of endodontic retreatment

The aim of retreatment is to perform an endodontic treatment that can render the treated tooth functional and comfortable again, allowing complete repair of the supporting structures. Before starting the retreatment, it is profoundly important to consider all interdisciplinary treatment options in terms of time, cost, prognosis and potential for patient satisfaction.

Читать дальше