The Morning Prayer (

XXI), a genre sculpture in which the religious theme is simply a pretext. Many considered the kneeling figure of the young woman in a nightdress to be a masterpiece due to its realism. However, a suspicion soon spread among critics that the sculptor had used plaster casts of the model and even of the fabric – which in fact he had – to make the piece, thus ignoring academic rules. Yet, with its incomparable naturalism that plays on pictorial values, the finely rendered physiognomy, and soft modelling – which, combined with the narrative element, evoke the figures in a waxworks – the piece melds tried and tested compositional models and early painting traditions with contemporary content. Thus, Vela’s work immediately met the taste of an influential elite, composed of liberal exponents of the Lombard nobility and the nascent upper middle class, whose common goal was to courageously resist the occupying power: the Austrian Monarchy that had governed since the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Vela’s art, whose vigorous style challenged the obligations and practices of the old school, soon became the cultural manifesto of the Milanese. The rising star was courted by men of letters and patrons, who had long awaited his arrival.

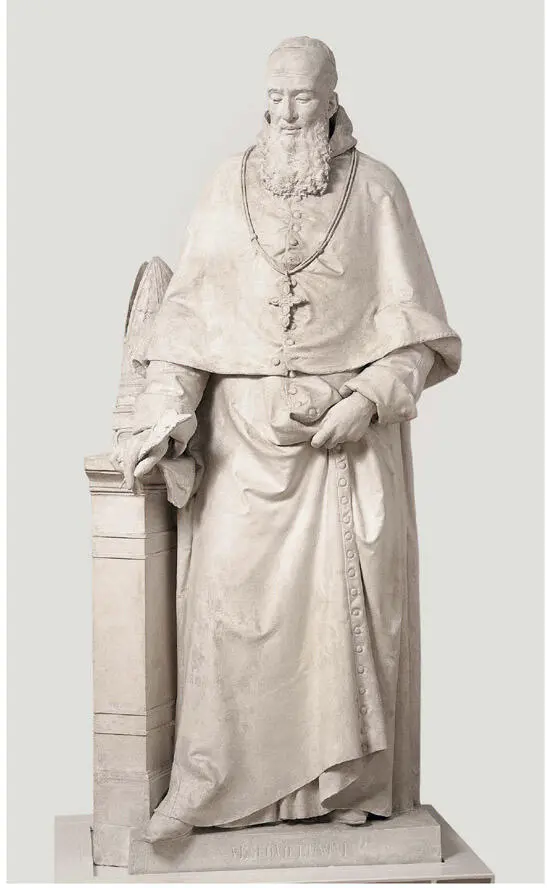

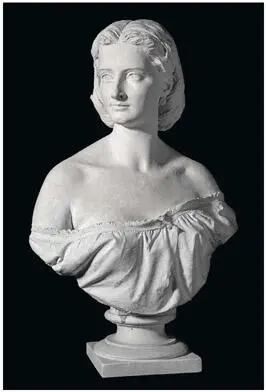

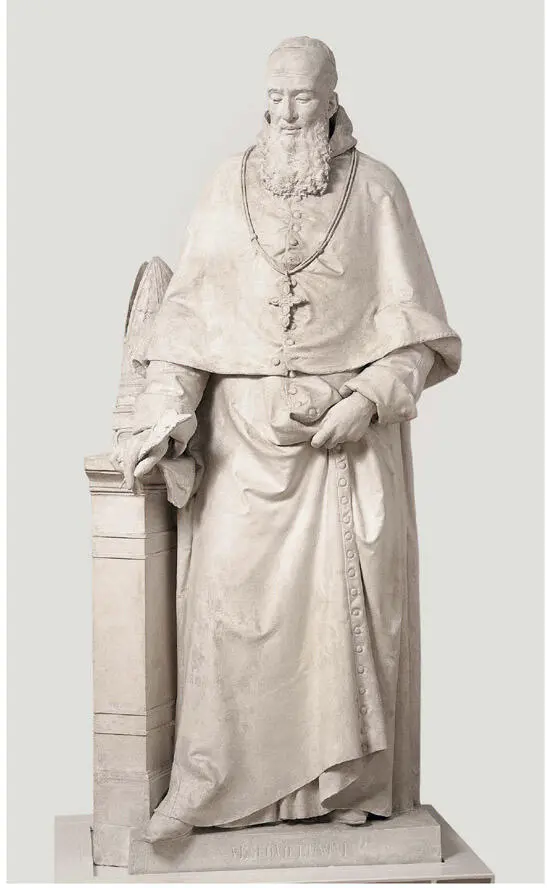

Vincenzo Vela, Monument to Giuseppe Maria Luvini, Bishop of Pesaro , 1844, plaster cast of Vincenzo Vela’s statue in Lugano 1895.

Vincenzo Vela, Morning Prayer , 1846, plaster original, three perspectives.

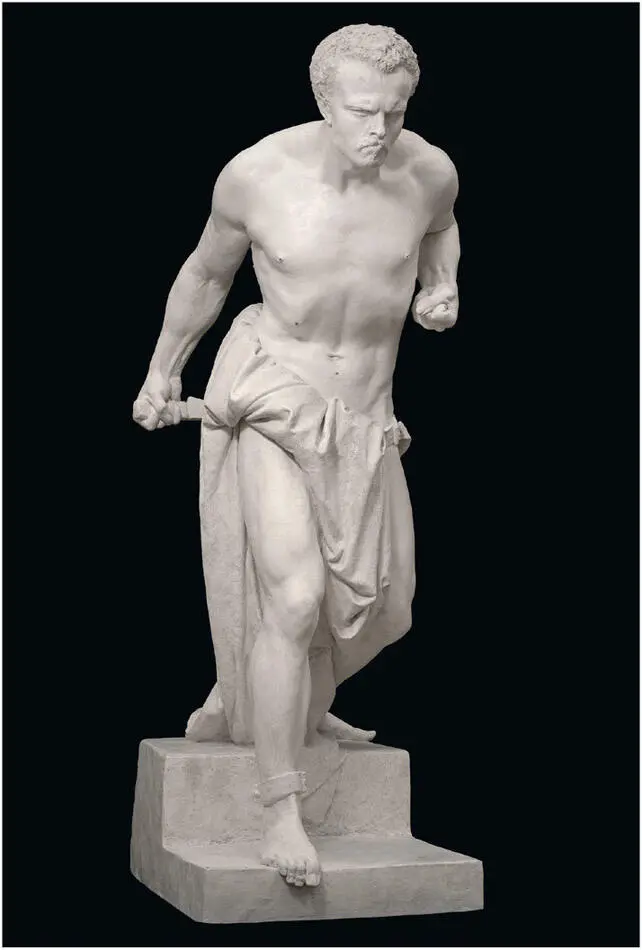

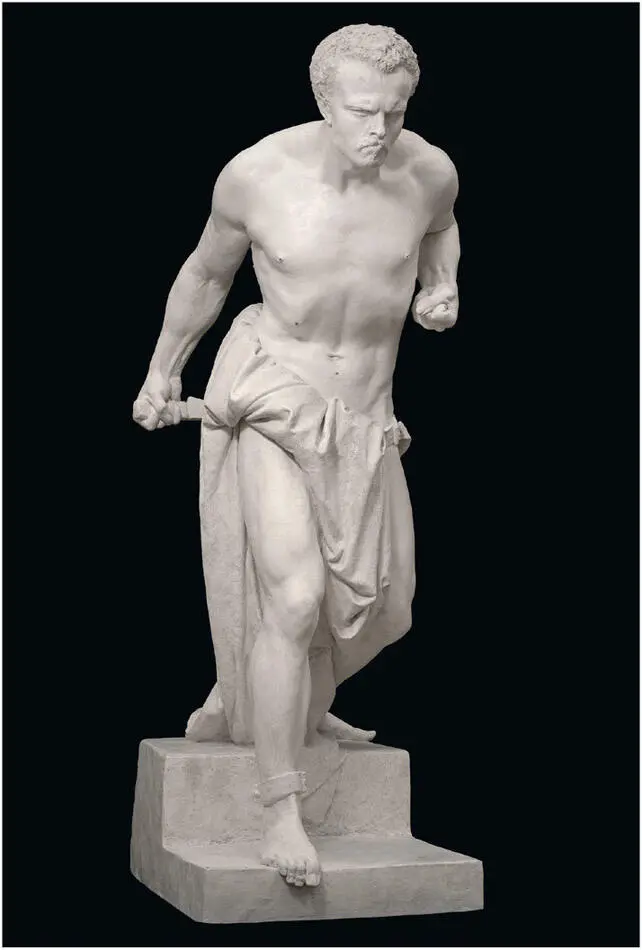

Spartacus , hero of the oppressed

Thanks to a colossal sculpture commissioned by the collector Duke Antonio Litta, in 1847 Vela received a grant that enabled him to work in Rome. He had just begun to design the model for this figure, Spartacus , when he decided to fight in the Sonderbund War, siding with General Guillaume-Henri Dufour (portrayed in 1849, II), and in March 1848, participated as a volunteer in the War of Independence fought by the Lombards against Austria, which ended with much blood spilled. On this occasion, the staunch republican earned the friendship and respect of the Milanese as well as the reputation of being a politically engaged artist and patriot.

His marble colossus, sculpted in winter 1849–1850, arrived on cue to mark the definitive demise of the formal canons of classicism ( VII, see ill. p. 8). The heroic slave who breaks his chains to die a free man became the symbol of the national uprising. Thus, Vela’s ‘verism‘ championed Italian unification and roused the people – as did the operas of Giuseppe Verdi.

Vela the revolutionary soon became a thorn in the side of the occupying power. When, in 1852, he refused the offer of an academic chair, which was intended to keep sympathizers of the opposition in their place, he had to take refuge in his own country, where he established friendships with many refugees. A few months later he emigrated to the free and liberal city of Turin, the hub of the Risorgimento. There he was able to count on new commissions and his influence began to be felt abroad.

Success soon followed: he made his name not only through numerous public and private sculpture commissions, but also his work as a professor at the Accademia Albertina, a position conferred on him in 1856 by King Vittorio Emanuele II. In the course of the next fourteen years he had the rare opportunity to spread his style, and in a relatively minor artistic milieu his art became an undisputed model. Based in the city that had the most political clout in the Italian peninsula, Vela had a profound and lasting influence on monumental sculpture throughout the country. In a short space of time verism came to be seen as the quintessence of Italian style, at home and abroad. The first works Vela executed in Turin were portraits, interpreted with psychological finesse, and numerous funerary monuments, mainly in the form of personifications in modern dress ( Hope , Desolation , Doleful Harmony , Our Lady of Sorrows ). Drawing inspiration from historic models, he came up with solutions that were as modern as they were astonishing, the archetype being the family chapel of the Counts d’Adda at Arcore, in which are represented Maria Isimbardi d’Adda on her deathbed (1851–1852) and Our Lady of Sorrows with Christ’s crown of thorns (1851–1853, XX).

1856 saw the solemn inauguration of the Monument commemorating Cesare Balbo , the first ever executed for a citizen of Turin. The statesman of noble birth is portrayed seated, in a pose that is not at all aristocratic: Vela has ‘fixed‘ the moment photographically, precisely at a time when photography was becoming an established medium, capturing the sitter in a typical position. Not only was this the first of an important group of works, it also gave rise to an actual cult of monuments, which began in France (where it was known as statuomanie ) and spread to the whole of Europe in the name of democratization. Squares and public spaces were no longer to be embellished solely with statues honouring princes and saints, but also with those dedicated to the contemporary heroes striving for Italian unification. Politicians and generals, but also philosophers, scientists and benefactors, physicians, industrialists, teachers, artists, poets and adventurers were immortalized in marble and placed on a pedestal as models of modern society. By establishing a dialogue with the new commissioners – mainly committees for monuments that had sprung up, which administered a fund created through subscriptions – Vela and his statues actively and symbolically illustrated the idea of a liberal, middle-class national state, which was still a vague, abstract notion for many.

Vincenzo Vela, Spartacus , 1847–1849, plaster original.

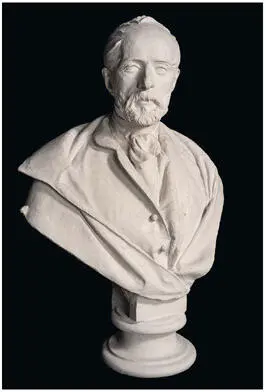

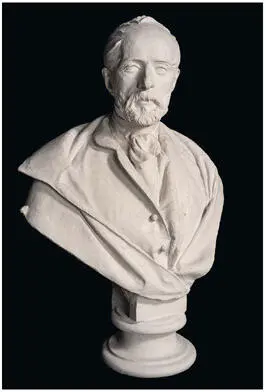

Vincenzo Vela, Portrait of Giovanni d’Adda , 1859, plaster original.

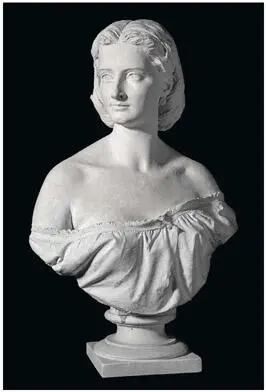

Vincenzo Vela, Portrait of Ballerina Amina Boschetti of Milan , c. 1853, plaster original.

Works by the master were soon followed by those of his pupils and his competitors. In the second half of the century, as many as fifty monuments were erected in Turin alone. It was a unique period, a golden era for sculptors, during which art and politics entered into strict symbiosis. This is exemplified by Vela’s Flag-Bearer (1857–1859, I, ill. p. 11, plinth relief see ill. p. 48) located in Piazza Castello, opposite Palazzo Madama, which actually functions as a manifesto. Donated by Milanese exiles to express their thanks to the Sardinian army for their assistance in 1848 during the first campaign against Austria, in 1859 the newly-inaugurated monument spurred the army that was once again marching against the enemy to unite Italy. Meanwhile, in Lombardy, the adversaries swore that the Flag-Bearer would be the first statue to be knocked off its pedestal when they entered the Piedmont capital.

Читать дальше