The high-risk group is primarily associated with a low socioeconomic status that leads to less sufficient oral hygiene, fluoride exposure, and often more frequent sugar intake. 2, 5

In the primary dentition and especially for early childhood caries, the situation is far from satisfactory in many countries. 6In spite of a less pronounced caries decline in the primary dentition, caries patterns and distribution are equivalent to the situation in adolescents. 7This is also true for caries in adults. 2Most likely a further caries decline will also increase the polarization in adults.

Due to the caries distribution after a major caries decline, primary caries prevention needs a dual strategy of maintaining the high levels of oral health in the majority of the population and trying to find intensified measures to improve the situation in the risk group mostly characterized by a low socioeconomic status. 3

There is a realistic perspective that caries levels even in risk groups can be significantly reduced in the future, as the caries decline in this group was proportional to the reductions in the whole population, at least in German adolescents. 4

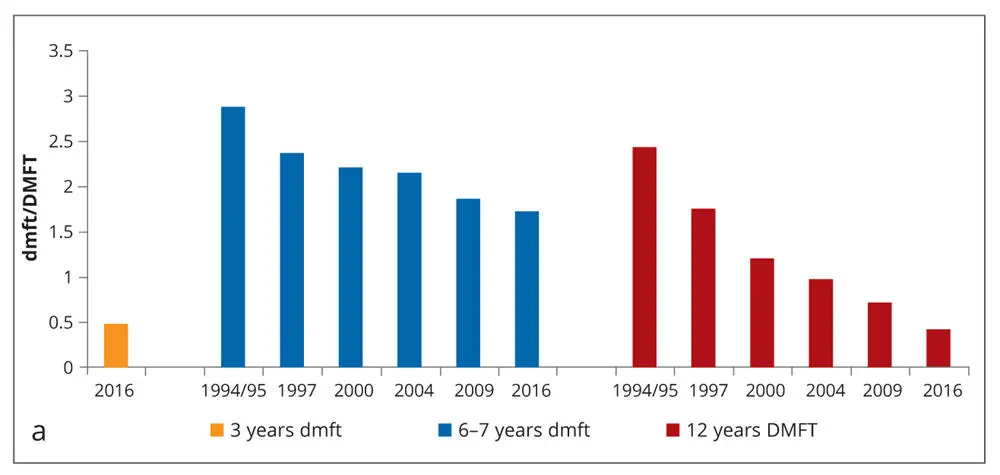

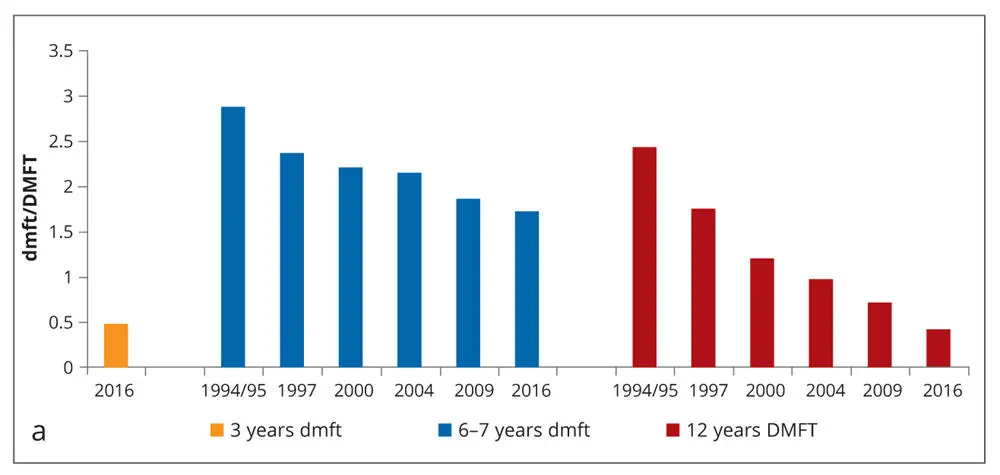

Figs 1-2a and bDecayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft/DMFT) in Germany in (a) schoolchildren, 3,7adolescents, 3,4and (b) adults. In many industrialized countries such as Germany, a remarkable caries decline has been recorded for the permanent dentition in adolescents, as well as in adults, and to a lesser extent for the primary dentition in schoolchildren.

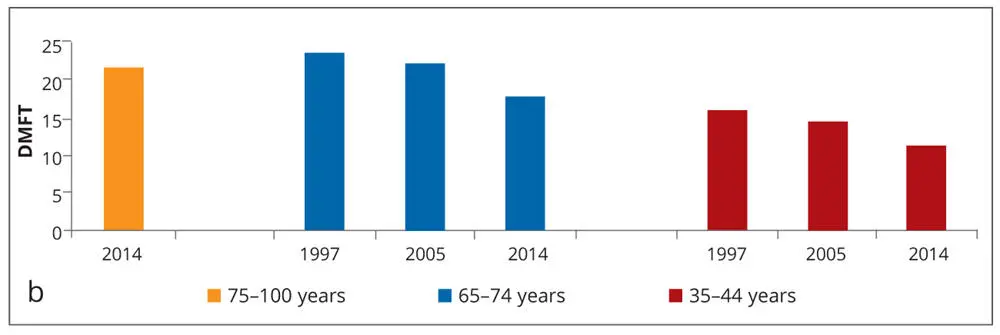

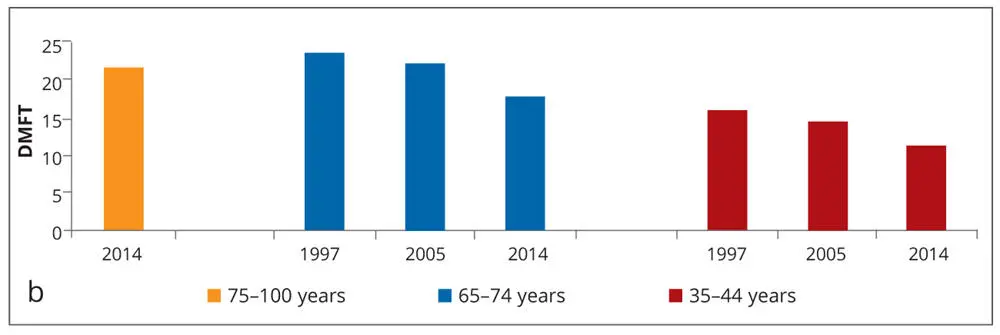

Figs 1-3a to dA large percentage of children are caries-free (80%) (a and b), while a small group of children (20%) (c and d) present with high caries rates (80%). The polarization of the caries distribution especially in children leads to two different preventive approaches: Maintaining the high degree of oral health in the majority group of the population and intensifying measures for the high caries risk group.

In contrast to the general caries decline in many industrialized countries, caries levels in the emerging market economies are still at a high level for most of the population, or even on the rise due to increased wealth and sugar consumption. 8This imposes a great challenge to these countries; in spite of choosing the restorative approach as was done by many Western countries, strengthening primary prevention would be a better choice.

The current epidemiologic situation of a polarized caries distribution calls for two distinctly different approaches to primary caries prevention: For the majority of the population, individual and professional prevention can reduce 90% of the caries burden and keep it at a tolerable very low level.

The so-called caries risk group that accumulates about 80% of the caries defects and the according treatment needs is characterized by a low socioeconomic status. It seems that outreach programs and tailored health regulations are necessary to achieve further health gains in the groups with often low self-efficacy or (oral) health literacy. A common risk factor approach and cooperation with other professionals are useful for risk grouptargeted prevention to strengthen health and probably also educational competencies in these individuals and their families.

Early childhood caries

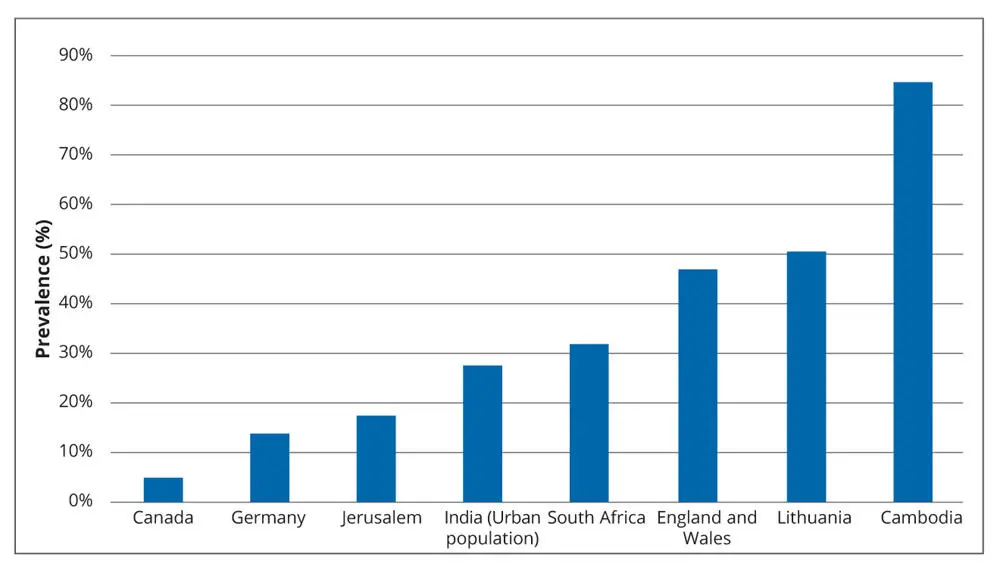

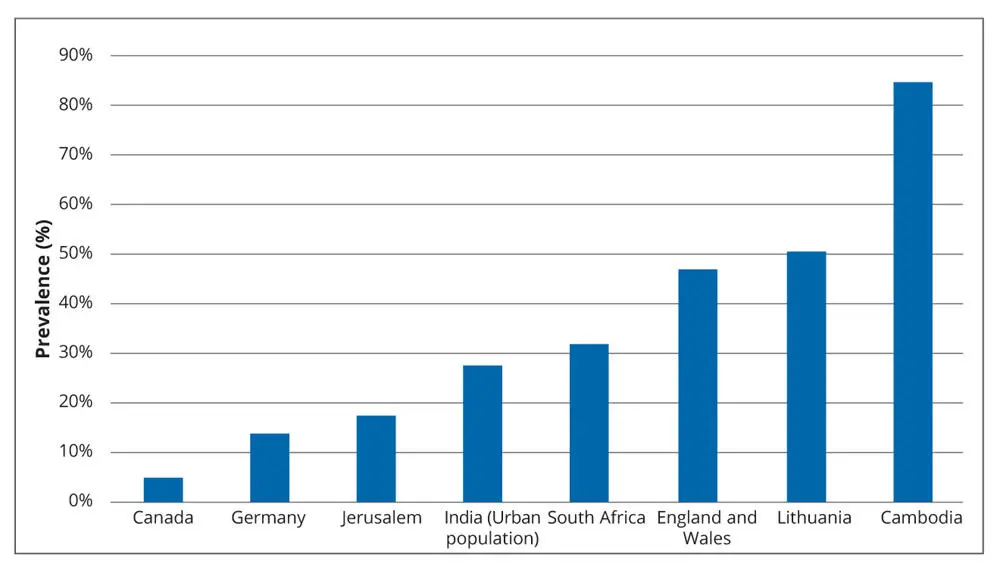

Early childhood caries (ECC) appears to be a persistent and neglected topic with rather high levels in many countries (Fig 1-4), low treatment rates, and, therefore, severe consequences in many small children that clearly affects their well-being and quality of life. 9

Fig 1-4Global epidemiology of early childhood caries (ECC). ECC or caries in the primary dentition seem to be a persistent problem, with severe consequences for the affected children. Preventive approaches in almost all countries have to be intensified to mirror the success often achieved in the permanent dentition. 3,10-16

Only in recent years has research in caries epidemiology focused on early childhood, followed by representative surveys on the prevalence of ECC. Thus, ECC deserves special attention in order to draw conclusions that might deviate from the situation in the permanent dentition.

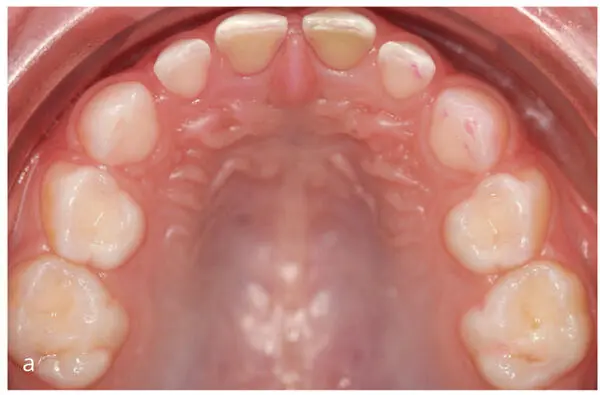

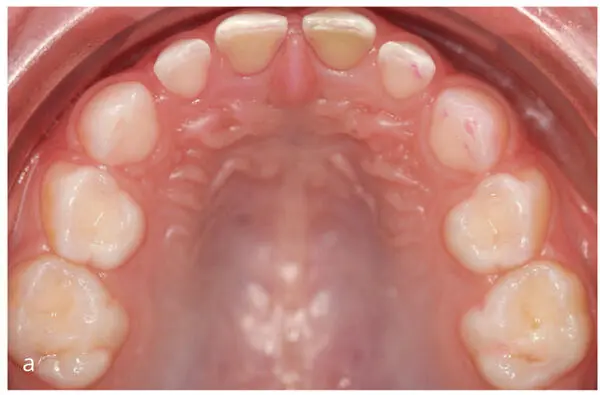

ORCA and IADR define ECC as “the early onset of caries in young children with often fast progression which can finally result in complete destruction of the primary dentition [Fig 1-1a]. An epidemiologic definition of ECC is the presence of one or more decayed (noncavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled surfaces, in any primary tooth of a child under [the] age of six.” They also state that the appearance of ECC deviates from the common caries distribution where pits, fissures, and proximal surface dominate. 1

“Due to the frequent consumption of carbohydrates, especially sugars, and inadequate to absent oral hygiene in small children, ECC demonstrates an atypical pattern of caries attack, particularly on smooth surfaces of upper anterior teeth.” 1This implies that typical ECC is a type of child neglect, as even minimal and easy preventive oral health measures are omitted for a considerable time. It is amazing that this can be found in so many children in developed and emerging countries. 6It also calls for clearly intensified primary caries-preventive measures from the first tooth on.

The National German Oral Health Survey in Children and Adolescents revealed 14% of 3-year-olds had caries on a dmft level in Germany, 3which is at the lower end of an international comparison. The mean value in the affected children (the newly introduced Specific affected Caries Index [SaC] 17) was 3.6 dmft, making pulpal involvement, subsequent toothache, and probably a treatment under general anesthesia (GA) due to the high number of carious teeth as well as the low compliance in these small children likely – or a painful, and potentially traumatic experience when extraction in uncooperative children is performed if GA is not available. 3

A closer look reveals that in spite of a very low mean caries prevalence of 0.3 dmft in 2-year-olds, a small risk group of children develops “real” ECC from the first tooth onwards ( Table 1-1). Here ECC is caused by infant feeding that provides a high sugar content and/or erosive drinks in combination with insufficient or a complete lack of oral hygiene. 18Regarding the “epidemiologic” definition of ECC, in Germany the prevalence increases to almost 35% at a defect level until school age. 3,7The care index of less than 50% is not satisfactory, and clearly lower than in the permanent dentition. 3The young age of the children and the high burden of the disease in many countries make a primary preventive approach to manage the problem of ECC (see Chapters 5and 9) more logical than the secondary or tertiary prevention (see Chapters 12to 14) via, for example, restorations or even extractions.

Читать дальше