1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...35

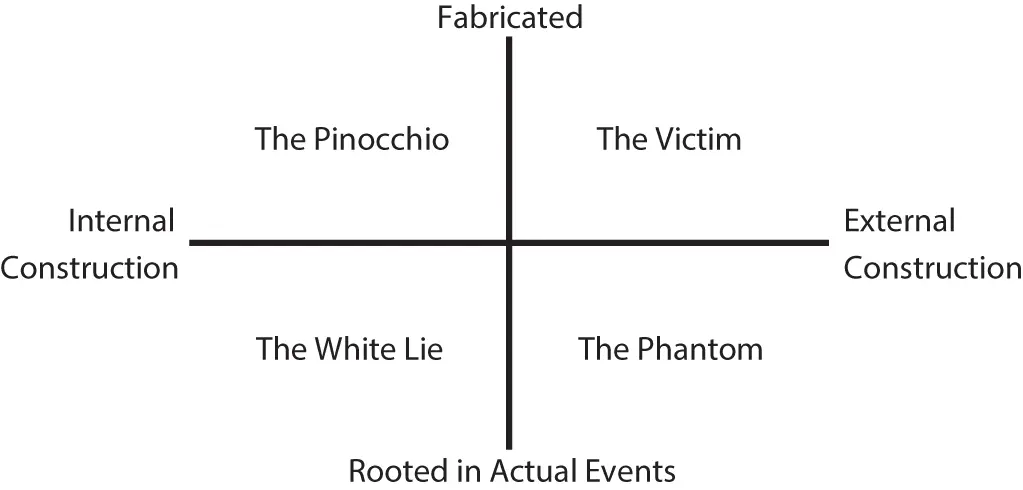

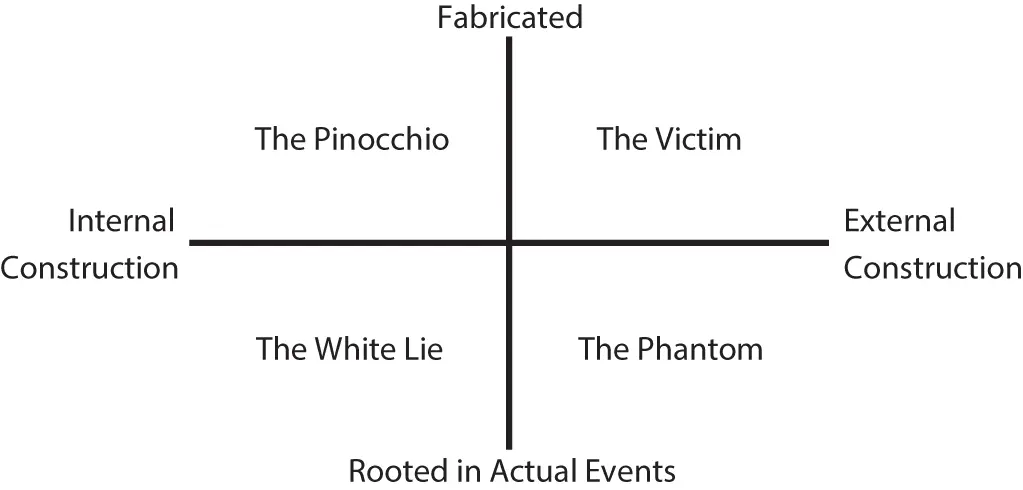

Figure 2.3 Quadrant typology of deception forms. Source : Ferreira et al. (2020). © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited.

Table 2.3 A typology of fake news definitions.

| Level of Facticity |

Author’s Immediate Intention to Deceive |

| High |

Low |

| High |

Native advertising Propaganda |

News satire |

| Low |

Fabrication |

News parody |

| Source : Adapted from Tandoc et al. (2017). |

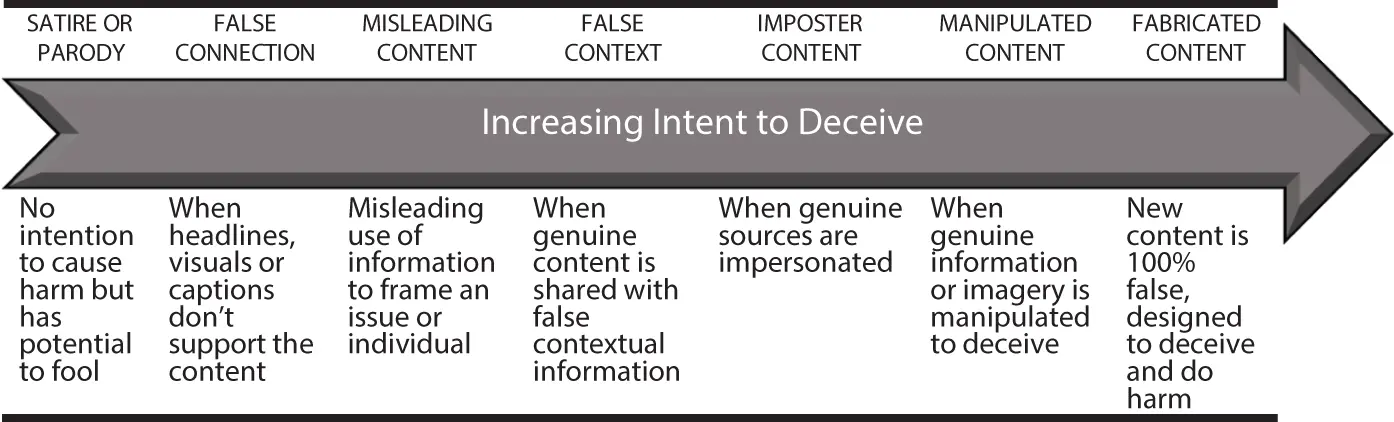

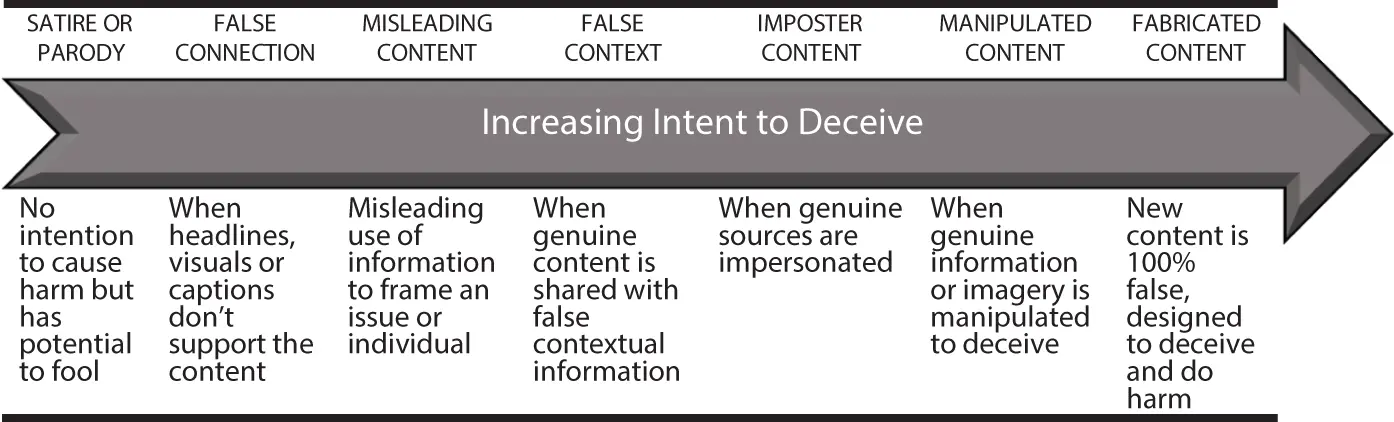

UNESCO (2018) adopted a unidimensional spectrum of intent to deceive in differentiating seven types of what they describe as information disorder (see Figure 2.4). This typology was intended to assist in ethical journalism education and practice. As such, it distinguishes both genres (e.g., satire or parody) and various degrees of falsification, largely arrayed by the quantity of fabricated content. UNESCO further differentiated the various dimensions along which information disorders vary ( Table 2.4). Some of these dimensions are particularly insightful, such as the recognition of the increasing role of AI and bots in generating false content.

Figure 2.4 Deceptive intention spectrum of information distortion. Source : Adapted from UNESCO (2018), attributed to firstdraftnews.org.

Table 2.4 Dimensions of information disorder. Source: Based on UNESCO (2018).

|

Dimension |

Exemplars |

| Agent |

Actor type: Level of organization: Type of motivation: Level of automation: Intended audience: Intent to harm: Intent to mislead: |

Official/Unofficial None/Loose/Tight/Networked Financial/Political/Social/Psychological Human/Cyborg/Bot Members/Social Groups/Entire Societies Yes/No Yes/No |

| Message |

Duration: Accuracy: Legality: Imposter type: Message target: |

Long-term/Short-term/Event-based Misleading/Manipulated/Fabricated Legal/Illegal No/Brand/Individual Individual/Organization/Social Group/Entire Society |

| Interpreter |

Message reading: Action taken: |

Hegemonic/Oppositional/Negotiated Ignored/Shared in support/Shared in opposition |

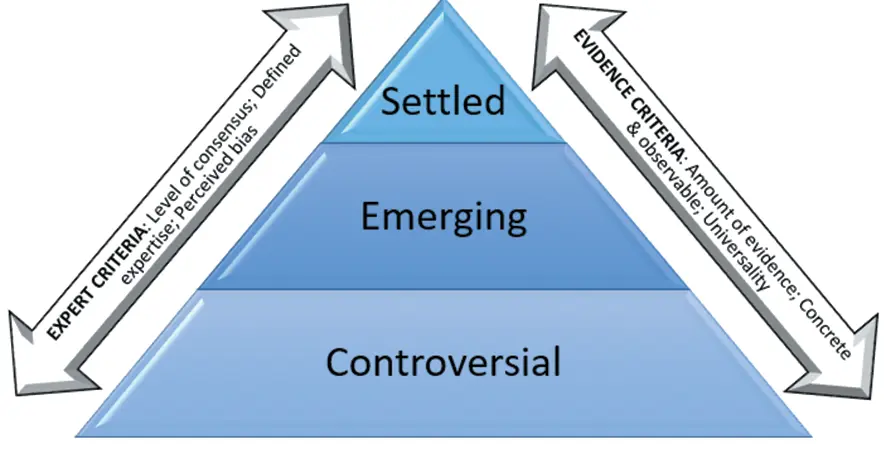

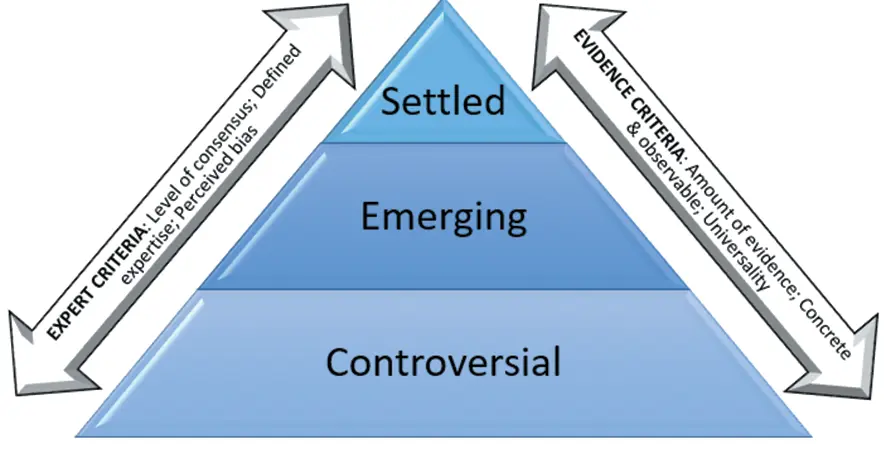

Vraga and Bode (2020) sought to frame misinformation in a context that recognizes the normative nature of truth or reality. Given the philosophical and epistemological challenges of determining a ground state of truth, Vraga and Bode suggested a continuum of how settled and warranted the reality is in its discrepancy from the information provided (see Figure 2.5). They thereby recommend three relative states through which information can progress or shift: from controversial to a more emergent reality to more settled truth status. This typology seems well-suited to discussions of the particular forms of dismisinformation of pseudoscience and conspiracy theories.

Figure 2.5 Contextual typology of misinformation. Source : Adapted from Vraga and Bode (2020).

While most of these typologies of dismisinformation have been deductive in nature, other approaches have been more inductive in development. Kalyanam et al. (2015) used coder annotation and machine learning to automatically classify “credible” and “speculative” tweets regarding the Ebola outbreak. Sell et al. (2020) examined a 1% sample of all tweets between September 30 and October 30 during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, focusing on a random subsample of the 72,775 tweets in English mentioning “Ebola.” They coded this tweets subset (N = 3,113) for their veracity (true, false, and partially false) and if their intent was a joke, opinion, or discord. Of the non-joking tweets, 5% contained false information and another 5% contained partially false/misinterpreted information, often consisting of debunked rumors. Importantly, the misinformation tweets were more likely than the true tweets to be discord-inducing (45% vs. 26%), or tweets designed to evoke conflict from other Twitter users. Similarly, Oyeyemi et al. (2014) distinguished “medically correct information,” “medical misinformation,” and “other” (e.g., spiritual) tweets about Ebola in three countries in west Africa and found that most (55.5%) tweets and retweets contained misinformation, with a potential reach of over 15 million potential readers. Jin et al. (2014) examined 10 common rumors in tweets related to the Ebola outbreak in September through late October 2014 and found that although rumors were common, “they were a small fraction of information propagated on Twitter” (p. 91) and were “more localized, distributed and comparatively smaller in permeation than news stories” (p. 92). Brennen et al. (2020) analyzed 225 pieces of misinformation about COVID-19 from a news fact-checking service, 88% of which were from social media platforms. They distinguished what they referred to as reconfiguration (i.e., “where existing and often true information is spun, twisted, recontextualized, or reworked,” which constituted 59% of the instances) from completely fabricated instances, which represented 38% of the information (p. 1). They further distinguished reconfigured information as misleading content (29%), false context (24%), or manipulated content (6%), whereas fabricated content was divided between imposter or impersonation content (8%) and fabricated content (30%). A remaining 3% of the messages represented satire or parody.

Based on over 20 million tweets across over 4 million users commenting on the 2018 state of the union address and 2016 presidential election, Bradshaw et al. (2020) developed an inductively generated typology of fake news based on five a priori criteria: professionalism (i.e., “purposefully refrain from providing clear information about real authors, editors, publishers, and owners, and they do not publish corrections of debunked information,” p. 176); counterfeit (i.e., “sources mimic established news reporting by using certain fonts, having branding, and employing content strategies,” p. 176); style (i.e., “propaganda techniques to persuade users at an emotional, rather than cognitive, level,” p. 177); bias (i.e., “highly biased, ideologically skewed” publishing “opinion pieces as news,” p. 177); and credibility (i.e., “report on unsubstantiated claims and rely on conspiratorial and dubious sources,” p. 178). The result was a five-category typology of political news (professional news outlets, professional political sources, divisive and conspiracy sources, other political news and information, and “other”), allowing a direct dichotomous comparison between “professional” news outlets and “divisive and conspiracy sources.”

Fake news takes numerous potential forms of misinformation in the transmedia environment (e.g., Tandoc et al., 2017), including “false connection (subtitles that do not correspond to the content), false context, context manipulation, satire or parody (without explicit intentionality), misleading content (misuse of data), deceiving content (use of false sources), and made-up content (with the intention of manipulating public opinion and harming)” (Alzamora & Andrade, 2019, p. 110). Just as importantly, however, are the distinctions between fake news and some of its conceptual cousins that would be excluded from such definitions or operationalizations of fake news. For example, fake news is distinct from (i) unintentional informational mistakes, (ii) rumors that do not derive from news, (iii) conspiracy theories, which are likely to be believed as true by their propagators, (iv) satire not intended to be factual, (v) false statements made by politicians, and (vi) messages intended and framed as opinion pieces or editorials (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). Others have attempted to distinguish “serious fabrications,” “large scale hoaxes,” and “humorous fakes” such as stories in The Onion (Bondielli & Marcelloni, 2019). There are, however, gray areas among these. For example, a politician’s false statements that are reported without any critical concern for their veracity (i.e., reported as a priori factual or potentially factual), or conspiracy theories that contain or rely upon verifiably false claims, may well overlap fake news, especially when news reporting itself gets duped by such false forms of information. Alternatively, conspiracy theories have been typologized by the extent to which they reflect (i) general versus specific content and structure, (ii) scientific versus non-scientific topics, (iii) ideological versus neutral valence, (iv) official versus anti-institutional agendas, and (v) alternative explanations versus denials (Huneman & Vorms, 2018).

Читать дальше