However, more than these studies, the awareness of the media, the public and decision-makers has probably taken place through the epiphenomenon of the rare earth crisis (used in many offshore wind turbines). The soaring price of lanthanides quickly triggered deep concerns among industrialists and the general public. And what if, beyond the geopolitical crisis, our world was to enter a mining impasse, sending the boom in renewable energies halfway into limbo for lack of metals?

Moreover, the many reports and photos of workers in artisanal cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in rare earth mines in China remind us that environmental sustainability in industrialized countries is meaningless if it is not also part of a socially just and economically secure support for all citizens of the world.

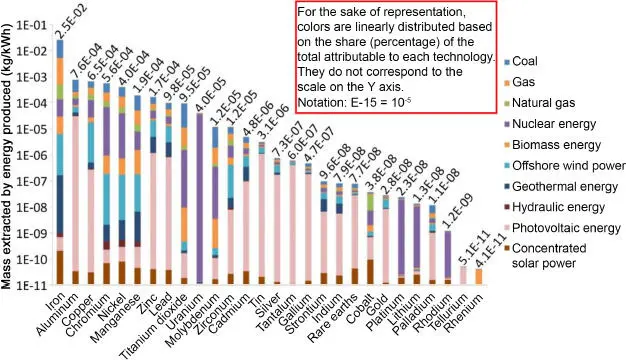

Figure I.1. Material footprint of various power generation production systems (source: data from Boubault (2018)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/fizaine/mineral1.zip

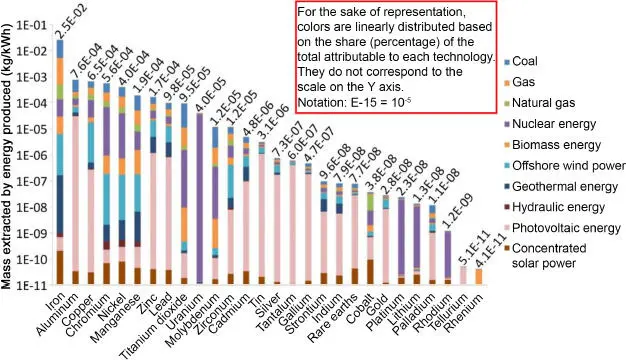

Figure I.2. Metal footprint per kWh by type of power generation system (source: data from Boubault (2018))

Figure I.3. Share of metal footprint of the electricity sector by power generation system (source: data from Boubault (2018)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/fizaine/mineral1.zip

Although a number of technological impasses have been identified and many points of tension on particular resources must be thwarted with these insights, the realization has nevertheless opened up a lot of thinking on all fronts.

I.1. Systemic mechanics associated with multiple corollaries: insights provided by interdisciplinarity

This book aims to explore, identify and explain the possible bottlenecks associated with the use of mineral resources. The question of the use of mineral resources does not only arise in terms of the quantities available. An open, prospective and interdisciplinary reflection is, thus, necessary to accomplish this task . We have, therefore, mobilized a large team of researchers and thinkers on various issues associated with mineral resources. There are economists, of course, and also physicists, engineers, geologists, lawyers and geographers. This book also helps to bring together specialists working on this theme, often still too isolated and without any real lasting connections. Of course, there are many initiatives, such as the Association française des économistes de l’environnement et des ressources (FAERE, French Association of Environment and Resource Economists), the team around the “Cyclope” report or the contributions to the mineral-info.frsite, but these are still too fragmented or monodisciplinary compared to other much more unified fields like energy. It is also because energy is already entitled to large interdisciplinary teams that we have chosen to focus on mineral resources and exclude energy minerals from our scope of analysis.

To initiate this reflection, we have decided to adopt a structured approach based on three axes: context, issues and leverages of action, spread over two separate volumes. In Volume 1 of this work, the first axis – context – retraces a few elements that allow for a better understanding of the situation of mineral resources.

First of all, while mineral resources are at the heart of the most advanced technologies, a detailed knowledge of their flows is required in order to assess their demand. This is what Raphaël Danino-Perraud, Maïté Legleuher and Dominique Guyonnet ( Chapter 1) focus on in relation to the cobalt market. For example, extraction and refining are highly concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo and China, respectively. The assessment of its demand in Europe uses the so-called “material flow analysis” (MFA) approach, which traces these flows and takes into account the multiple forms and uses of cobalt and its recycling possibilities, all the way to the “urban mine”. This MFA of cobalt, coupled with a value chain analysis based on European data, makes it possible to question the strategies of European groups that, anxious to position themselves in high value-added segments, end up dependent on operators working upstream (extraction and refining).

Some mineral resources are financialized while others are not and this has important consequences on the transparency and price dynamics prevailing in these markets. With this in mind, Yves Jégourel ( Chapter 2) describes the role of the financialization of ore and metals. More specifically, the author reviews the organization and mechanisms of futures and their alternatives. The author also discusses the effect of financialization on the dynamics of mineral prices and also on the transformation of the sectors using them.

Beyond the financial aspects, the supply of mining resources is also part of institutions – in the first place, state policy. As such, not all countries seem to follow the same rules. While many have established a doctrine for the management of energy resources, this is not the case for mineral resources. Didier Julienne ( Chapter 3) attempts to deconstruct the myth that countries are genuinely opposed to each other in order to get their hands on metals. In reality, countries such as China, which has a real resources doctrine, are advancing their pawns to secure their future supplies without encountering any real resistance from industrialized countries. The author calls for the reconstruction of a genuine resource strategy in Western countries and for stopping the over-reaction to often truncated economic information.

To assess the amount of mineral resources available to our economies, we use indicators that we rarely question. This is what Michel Jébrak ( Chapter 4) does do. In particular, he demonstrates that mineral endowment is a complex concept that can be measured using different parameters: the annual production of a specific mineral and its reserves and their ratio, which can vary in terms of upward or downward trends for different minerals. This endowment can be generalized by the notion of basic reserves, which attempts to assess the overall geological potential of a given metal. If mineral resources are unevenly distributed geographically, their exploitation moves from one country to another according to the movement of industrialization, as in the case of the main copper and tin mines. Ultimately, mineral endowment is a historical construct, dependent on geological data, mineral extraction and processing technologies, and on the economics of mining, which is a capital-intensive industry.

The second part of this book reports on the challenges that mineral resources face. They concern the multiple factors that can affect the supply of mineral resources.

In a chapter focusing on the struggle between technical progress and the geological depletion of metal deposits, Olivier Vidal ( Chapter 5) shows how two antagonistic approaches (optimistic and pessimistic) can be pooled into a formal approach of dilution–energy and energy–price relationships. Using formal theoretical tools, as well as empirical calibration on past data, he questions the perpetuation of observable price declines for most metals. This downward trend in prices should be reversed by the end of the century if the rate of technical improvement remains the same and if we continue to exploit increasingly less concentrated deposits.

Читать дальше