Then it was that the officers of the stage company sent for Bill. He promptly reported at St. Joseph for a council of war. Nobody knew what to do until he spoke up and, according to the record, delivered himself of the following brief but pointed speech:

“You have enough men here, if they are turned loose right, to clean out all the red devils along the route, and all the men now idle would consider it a frolic to go into Indian service for a short time.”

That settled it. Wild Bill was told to go ahead and see what he could do, and when he was getting ready for a fight he was an ardent party. He called the men together and told them what was wanted. Fifty men enlisted with a hearty good will, all promising implicit obedience with Bill as leader. This well-equipped band, under a commander just twenty-one years of age, started away from St. Joseph, Missouri, on the 29th of September, 1858. Arriving at Powder River, where they expected to find the Indians encamped, they found nothing but dead ashes and tracks that pointed westward. They followed and in three days came upon the Indians at Crazy Woman’s Fork. The original band had meanwhile doubled in number and all were painted up and ready to go anywhere they might cause trouble.

Discovering the extent of the camp, some of the band suggested that they return to St. Joseph. Bill told them that he would shoot the first man who turned his back on the enterprise. Here was a force of four to one against them, but that didn’t bother the young leader. He had with him a crowd of young dare-devils who, one picturesque chronicler remarked, could be depended upon to fight a ten-acre field full of grizzly bears with only a toothpick for a weapon.

At some little distance smoke in the tree-tops was discovered. That meant an Indian camp. Bill ordered his men to halt, to give him a chance to locate the game. Alone he made a broad circuit to reach high ground, in order to ascertain the extent of the camp and learn where the horses were tethered.

This was done and a plan of battle devised. Bill ordered his men to rest till nightfall and to light no fires that would serve to attract the foe. At ten p. m. Bill called his men to saddle and gave his instructions. Each man was ordered to follow him into the Indian camp and each to fight only with his pistol; to make for the stock which, being in a corral, would be easily stampeded and run out, and then collected and secured.

These commands, according to the best information, were strictly obeyed. A dash was made for the corral by a dozen of the men, while the other rode en masse into the Indian camp. The amazed savages dashed out of their tents in order to learn what the racket was about, and were shot down before they could lay hands on their arms.

One of the young scamps who followed Bill in this high emprise was young Will Cody, afterward known as Buffalo Bill. The party returned to St. Joseph with all the horses which had been stolen from the stage company, and with upward of one hundred more belonging to the Indians. Bill had taught the redskins a lesson they never forgot. An end was written to stagecoach massacres.

Next year, 1859, Bill left the employ of the Overland Stage Company, and engaged as driver with the famous freighters, Majors and Russell, for a long and hazardous trip between Independence, Missouri, and Sante Fe, New Mexico. It was at this time that he had his famous fight with a bear, to which so many references have been made by writers of frontier literature.

While passing through the Soccoro range with his team, travelling two miles ahead of his companion, Matt Farley, he encountered a big cinnamon bear in the road. Having two cubs with her, the bear betrayed not the slightest intention of getting out of the way; instead, she showed fight. Bill, provided with his brace of pistols and a good hunting knife, was not much concerned. Instead of staying on his wagon, which would have been the better part of valour, he sprang to the ground, imagining that it was an easy job to kill a bear.

But not this mother bear. When she had snarlingly approached within a short distance from him, Bill let fly with one of his pistols and caught the cinnamon between the eyes. It appears, as Bill subsequently discovered, that in the case of a bear of her size and family, the spot was ill-chosen. The bullet merely glanced off the skull and resulted only in making the animal more truculent.

She charged.

Bill was too far away from the wagon to gain its security, so nothing was left for him to do but fight. And when man or bear put it up to Wild Bill to have a fight, a good brand of tumult was generally provided.

His next shot injured the animal's left fore leg. The bear reared on her haunches and grappled with her foe. Bill resorted to his knife and thrust it into the animal’s body again and again, and into stomach and throat, but the infuriated beast fought on.

Bill had suffered several frightful lacerations. The ground was wet with blood, and still he was unable to escape the embrace of the infuriated bear. Finally the two antagonists slipped to the ground, Bill underneath with his left arm in the bear’s mouth. In this position he found that he could use his knife with greater effectiveness.

In the end, Bill literally disembowelled his antagonist. At the finish it was difficult to say which presented the more horrible spectacle, Bill or the bear. But Bill was alive and the bear dead. That is the way it always happened when Bill got into a fight. But this time he was badly wounded and when Farley drove up he took him to Santa Fe, where he was placed in the care of a capable surgeon. It was several months before he was able to do any active work.

It was two years prior to this time that Bill cut into the trail of Buffalo Bill Cody, and as a result of that meeting they remained fast friends throughout their lives. Wild Bill was then twenty and Will Cody but eleven years of age. In his various biographies, and in his oft-quoted reminiscences, Buffalo Bill made much of this incident. Having lost his father, young Cody had joined an expedition over the Salt Lake trail, and having been transferred to Lew Simpson's wagon train, he unexpectedly encountered Wild Bill. One day the men were treating the Cody youth rather roughly. Suddenly there came out from under a wagon a young giant.

“What are you fellows trying to do with that boy?” he asked.

One of the men told the interloper to attend to his own business.

“Well, if you fellows really want to fight, tackle me and let that boy alone,” Bill replied to this.

The man who came to young Cody’s assistance was Wild Bill.

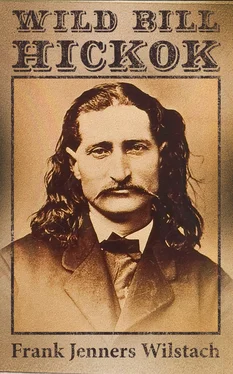

All along in this record, James Butler Hickok has been referred to as Wild Bill. How he gained this sobriquet is in doubt. Lifelong friends have expressed themselves as being in the dark in the matter. How the mistake was made of substituting William for James is open to conjecture. When Bill Cody first met him on the plains, he tells us, Wild Bill was called Jim Hickok.'

In an effort to supply a reason for the nickname, Buffalo Bill said his friend acquired it through a misunderstanding or mistaken identity. He said that young Jim Hickok at the time above referred to had an elder brother named Bill Hickok, who for several years had been a celebrated plainsman, and famed as being one of the best wagon-masters in charge of the great government trains, with all their responsibilities. He became famous for his courage, ability to command men, to defend the interests of his employees, to stand off the Indians and bandits that preyed on the wagon trains, and for his control of the dare-devil spirits who drove the teams. His younger brother, James, according to this account, rose so rapidly that rumour soon identified him with his elder brother, William—the result being that he was known throughout the West as Wild Bill Hickok.

Читать дальше