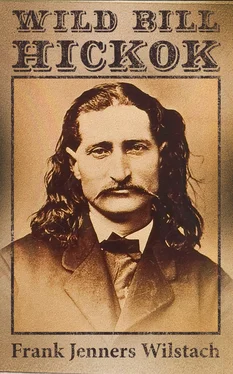

Wild Bill’s first employment was as tow-path driver on the Illinois and Michigan canal. It appears that he did not long remain away from home, and the reason for this was that he had had a difference with a man named Hudson. The two engaged in a fist fight which lasted more than an hour. The battle began on the tow-path, the fighters finally rolling into the water. Then followed efforts on the part of each to drown the other. Young Bill, despite the fact that Hudson was a powerful fellow, overcame this advantage by his extraordinary agility and finally won a decided victory. Hudson was taken from the water in an almost lifeless state, and it was only by the greatest exertion that he was resuscitated. This is the first exploit of his career which illustrates the truth of the saying long current along the border: “Wild Bill is a bad man to fool with.”

In 1855, when camped on the sunshine side of twenty, he decided that the time had arrived for him to venture forth into the world. From what he had read and heard, he knew that the territory west of Missouri was the habitation of Indian tribes; a vast area destined to become the states of Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, etc. The Indians in that immense stretch of country comprised the Shawnese, Delawares, Kickapoos, Osages, and other tribes; but Kansas was wild enough in those days to satisfy all his longings. It was, however, neither freedom nor Indians that had attracted his attention, but rather the struggles between more or less law-abiding factions in Missouri and Kansas. Here was a theatre of action that must have had a strong appeal to so venturesome a spirit. Wild Bill was an ardent Unionist and he probably sensed, as has been said, that the great need of that section was heroes. Somehow, during all his life he always headed for that point where the largest amount of trouble existed; and it was his ardent purpose, backed by his flaming hardware, to put it down and restore the peace.

So, gathering his pistol, hunting-knife, and rifle, he bade adieu to his mother, brothers, and sisters, and headed on foot for St. Louis. He reached his destination after a weary march of many days. To him the city was a marvel, but it was not altogether to his liking. After a few days of sightseeing he longed to tread the road of adventure, and so engaged passage on a steamer bound for Leavenworth. Arriving at that haven he discovered to his dismay that the town was in a tumult and that for political reasons no passengers were permitted to land from the boat.

That didn’t bother him any; he had started for Leavenworth and that was where he was going to stop, mob or no mob. He resorted to the expedient of disguising himself as a roustabout and began to unload freight. In this manner he succeeded in frustrating the angry and suspicious citizenry. He then learned that Jim Lane, the recognized leader of the Red Legs, an anti-slavery organization in Kansas, had recently arrived in Leavenworth from Indiana with a contingent of two to three hundred men.

Within a few days he had joined the forces of Lane, but to become a Red Leg it was necessary that the recruit demonstrate his proficiency as a marksman—which he did in the spectacular fashion already recounted.

For several months he was identified with the Red Legs and came to be recognized by Lane, according to the fable, as “the most effective man in his command.”

The records show that in 1857 he filed a claim for one hundred and sixty acres in Monticello Township, Johnson County, Kansas. Although he was not yet of age, his reputation as a fighter and dead shot had been heralded far and wide, with the result that he was elected constable. This was Wild Bill’s first post as peace officer. He buckled on his pistols and announced that he proposed that peace and order should reign in his bailiwick, and it did.

We now come upon a piece of information which has not found its way into the records. During this period Wild Bill married a young squaw after the Indian fashion, which was not regarded as binding. This knowledge I have from William E. Connelley, the present secretary of the Kansas State Historical Society,of Topeka, Kansas. Mr. Connelley says on the subject:

“There is no record of Wild Bill’s life among the Shawnee Indians. The old settlers of Johnson County, Kansas, whom I interviewed a good many years ago, and who are all now on the other side, gave me what information I have.”

This alleged Indian marriage was never mentioned, so far as I can discover, by Wild Bill in after years; but there are other beautiful Indian maidens who will be heard of later on, and of whom there is ample evidence.

But, squaw or no squaw, Bill was not allowed to live in peace on his Kansas homestead. As a member of Jim Lane’s Red Legs, he had administered a severe chastisement to the Border Ruffians of Missouri. They bore him a particular grudge, and this they set about to pay back inkind. In one of their predatory incursions on Kansas soil they burned his cabin. Wild Bill was absent at the time. What might have been written on the ample pages of history, had Bill been on hand, it is unnecessary to cogitate. A new cabin was built and this one also, while Constable Hickok was away from home, was laid in ashes.

Wild Bill now decided that he had had enough of Johnson County, Kansas. A new field of operations was opened to him by the offer of a position as driver for the Overland Stage Company. In this capacity he crossed the plains several times, operating from Missouri and Colorado and points in Kansas, Colorado, and Nebraska, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Salt Lake City. That was a lively life for a youth who only a short time before was killing wolves in La Salle County, Illinois, or fishing in Vermilion Creek at Troy Grove.

While he was apparently reckless, his friend J. W. Buel tells us that no man ever covered his routes with fewer accidents than Bill. And we are likewise informed that when nearing his destination it was his habit to treat the passengers “to a shaking up,” as he styled it, in “order to jolt the cricks out of their backs.” The particular stretch of road that interested him was that entering Santa Fe, New Mexico. There was a slight decline, and so Wild Bill invariably turned the horses loose and gave them the lash. So it was that the big coach bounded along “lurching the passengers from side to side, dishing up dyspeptics, phlegmatics, and rollicking dispositions indiscriminately, and bowling into the town finally the centre of a dust bank and the object of excited interest to everyone in the ancient Mexican city.”

Driving a stagecoach in those days was nothing like a cross-country motor journey of to-day. To get away with the job called for a steady nerve and an ability at all times to defend one’s self either with fists or pistols. Every station was located near a saloon and every stage employee was practically an animated skinful of fighting whisky. Desperate rows were as common as waxweed flowers on the prairie in springtime, and the man that had failed to snuff out a life was as a bashful fellow at a country dance—woefully out of place.

Such a condition of affairs did not daunt Wild Bill. It suited him to a dot. And that he was left pretty much alone is ample proof that even then, although a youth under age, he was a dangerous individual to meddle with. But this happy state of peace was arrived at only after several rough encounters in all of which he came off best; and, furthermore, at this time he was considered the best pistol shot on the plains.

But something far more menacing than the ruffians along the stage route now hove into view: the Indians of the Sweetwater broke out of their reservation and started on a rampage. They took to massacring settlers, killing Pony Express riders and, to bring matters to a handsome head, began to attack the stagecoaches. Having succeeded in this adventure—killing the driver and two passengers—they took to running off the stock of the company. That put an end to the stagecoach business in those parts for the time being.

Читать дальше