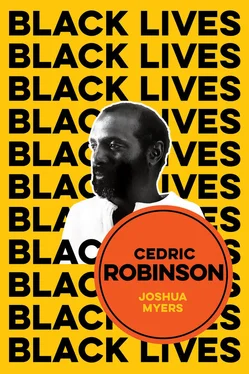

In a 1999 interview where he evoked Whiteside’s influence, Cedric also framed the question of genealogy and political struggle within the deeper registers of African cultural traditions. He reminded us of the importance that enslaved Africans gave to a “world view in which the reiteration of names (an African convention in which the name of a recently deceased loved one is given to the next child born) reflected the conservatism and responsibilities of a community.” As families grew, it was necessary to maintain “the resolve to value our historical and immediate interdependence.” 52The Whitesides had the ability to make Cedric Robinson, to inform his orientation, because he lived a life that tapped into an ongoing, living tradition of how to be in and beyond this anti-Black world – a tradition that would then be represented and made available to us. To reiterate their names within a project of and for Black Study is to remind ourselves that we too are interdependent. Our work is only possible when it is connected to communities of meaning that reside in spaces often held from view. It is an urgent and prescient meaning of intellectual genealogy.

1 1. In his biography accompanying a 1999 interview with Chuck Morse, Robinson placed Whiteside’s name, alongside C. L. R. James and the sociologist Terence Hopkins, as his “individuals or thinkers who had had the greatest influence upon his work.” Chuck Morse, “Capitalism, Marxism, and the Black Radical Tradition: An Interview with Cedric Robinson,” Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (Spring 1999): 6.

2 2. See, in particular, Greg Carr, “Toward an Intellectual History of Africana Studies: Genealogy and Normative Theory,” in Nathaniel Norment (ed.), The African American Studies Reader (Carolina Academic Press, 2006), 438–52.

3 3. See Kate Cote Gillin, Shrill Hurrahs: Women, Gender, and Racial Violence in South Carolina, 1865–1900 (University of South Carolina Press, 2013); Danielle McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance: A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (Vintage, 2010).

4 4. Cedric Robinson, Black Movements in America (Routledge, 1997), 116.

5 5. Robin D. G. Kelley, “Cedric J. Robinson: The Making of a Black Radical Intellectual,” Counterpunch, June 17, 2016, https://www.counterpunch.org/2016/06/17/cedric-j-robinson-the-making-of-a-black-radical-intellectual/

6 6. Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 170.

7 7. Robinson, Black Movements in America, 153.

8 8. Robinson, Black Marxism, xxx.

9 9. This section is based on the family research conducted by Robin D. G. Kelley in Robin D. G. Kelley, “Winston Whiteside and the Politics of the Possible,” in Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin (eds), Futures of Black Radicalism (Verso, 2017), 255–62.

10 10. Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery (University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

11 11. Michael W. Fitzgerald, Urban Emancipation: Popular Politics in Reconstruction Mobile, 1860–1890 (Louisiana University Press, 2002), 24.

12 12. Ibid., 152.

13 13. See ibid., 168–9, 233–8.

14 14. Ibid., 61.

15 15. Robert H. Woodrum, “‘The Past Has Taught Us a Lesson’: The International Longshoremen’s Association and Black Workers in Mobile, 1903–1913,” Alabama Review (April 2012): 113.

16 16. Woodrum, “The Past,” 7–11; Christopher MacGregor Scribner, “Progress versus Tradition in Mobile, 1900–1920,” in Michael Thomason (ed.), Mobile: A New History of Alabama’s First City (University of Alabama Press, 2001), 166–8.

17 17. Woodrum, “The Past.”

18 18. Scribner, “Progress versus Tradition.” See also David E. Alsobrook, “Alabama’s Port City: Mobile during the Progressive Era, 1896–1917” (PhD Diss., Auburn University, 1983), 152–91.

19 19. Delores Nason McBroome, Parallel Communities: African Americans in California’s East Bay, 1850–1963 (Garland, 1993), 55–90. See also Lawrence P. Crouchett, Lonnie G. Bunch III, and Martha Kendall Winnacker, Visions Toward Tomorrow: The History of the East Bay Afro-American Community, 1852–1977 (Northern California Center for Afro-American History and Life, 1989), 31–3.

20 20. Crouchett et al., Visions Toward Tomorrow, 9–10. For more on the significance of the porters in Oakland, see McBroome, Parallel Communities, 65–9.

21 21. Kelley, “Winston Whiteside,” 260.

22 22. Ibid., 261–2. On the foundations of Oakland’s religious community, see McBroome, Parallel Communities, 36–8.

23 23. Margot Dashiell, email communication, December 27, 2019.

24 24. “Helpful,” San Pedro News-Pilot, December 19, 1933.

25 25. Crouchett et al., Visions Toward Tomorrow, 35–41.

26 26. See Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton University Press, 2003), 53; and Crouchett et al., Visions Toward Tomorrow, 41. Oakland was not unique, as this period saw an increase in Black radical organizing that explicitly critiqued capitalism. See, among others, Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression (University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Minkah Makalani, In the Cause of Freedom: Radical Black Internationalism from Harlem to London, 1917–1939 (University of North Carolina Press, 2011); and Jonathan Scott Holloway, Confronting the Veil: Abram Harris, Jr, E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche (University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

27 27. Kelley, “Winston Whiteside,” 261.

28 28. Donna Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 26–7.

29 29. “25 Busy Years in Unemployment,” Oakland Tribune, May 16, 1965.

30 30. Kelley, “Winston Whiteside,” 256. The biographical details in the following paragraphs draw from this article, as well as Kelley, “Cedric J. Robinson.”

31 31. Kelley, “Winston Whiteside,” 262.

32 32. Margot Dashiell, email communication, December 27, 2019.

33 33. Elizabeth Robinson, personal communication, April 12, 2020.

34 34. Cedric Robinson, “Why Is There Black Radicalism?” Lecture presentation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, November 6, 2015, Youtube.com.

35 35. Robinson, Black Movements in America, 97.

36 36. Alain Locke, “The New Negro,” in Alain Locke (ed.), The New Negro (Albert and Charles Boni, 1925), 6.

37 37. Crouchett et al., Visions Toward Tomorrow, 45.

38 38. McBroome, Parallel Communities, 100–8.

39 39. “25 Busy Years.”

40 40. Self, American Babylon, 46–58; McBroome, Parallel Communities, 132–43.

41 41. Self, American Babylon, 45–6.

42 42. Ibid., 25–34, 58–60.

43 43. Chris Rhomberg, “White Nativism and Urban Politics: The 1920s Ku Klux Klan in Oakland, California,” Journal of American Ethnic History 17 (Winter 1998): 39–55.

44 44. Self, American Babylon, 96–100; Murch, Living for the City, 38–42.

45 45. Murch, Living for the City, 48–9.

46 46. Douglas Wachter, email communication, October 30, 2019; Margot Dashiell, personal communication, December 13, 2019; Joe Hibble to Cedric Robinson, November 16, 2010, CRP.

47 47. Kelley, “Cedric J. Robinson.” On tracking in Berkeley, see Berkeley Unified School District, De Facto Segregation Study Committee Report to the Board of Education (Berkeley Unified School District, 1963).

48 48. Cedric Robinson, “Joshua Fit De Battle …” English V Paper, January 8, 1957, CRP.

49 49. Elizabeth Robinson, personal communication, August 8, 2020.

Читать дальше