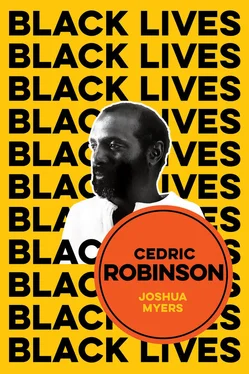

Cedric arrived onto the scene at perhaps one of the most critical junctures of western time: the mid-twentieth century. It was a moment where the hegemonic grip of western world order – the order that he would come to understand as constructed on a myth – was loosening thanks to the combined pressures of anticolonial and anti-imperialist movements across the globe. It was a freedom dream arrayed differently than the liberal model of political representation and economic ascendancy. And against an unsustainable market system underpinned by the violence of war and capitalist accumulation. In other words, it was a moment that saw revolution as a distinct possibility, even imperative to disrupting the time of western civilization permanently. In the wake of this moment in Black Marxism , Cedric wrote: “Everywhere one turns or cares to look, the signs of a collapsing world are evident; at the center, at its extremities, the systems of western power are fragmenting … the characteristic tendency of capitalist societies to amass violence for domination and exploitation [created] a diminishing return, a dialectic, in its use. ‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.’” 21

Cedric’s sojourn through the conceptual worlds of Black Study began in earnest in the early 1960s in the Bay Area, continued through the Midwestern and Northeastern United States, and into the United Kingdom, before finding settlement in Santa Barbara, California, where he served as the director of the Center of Black Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. It was here where he and his partner Elizabeth, and daughter Najda, made their home, where all five of his books were released, and where the communities of struggle that would significantly mark their lives – both on and off campus – were based.

It would be impossible, however, to understand this intellectual journey by solely focusing upon the academic contexts of the work. This is a journey that must also take into account what it meant to be raised by Black folks from Alabama. It has to think through the meaning of the organizing tradition of 1960s Oakland and the larger momentum of Black revolutionary work that spawned networks of activists, thinkers, and artists in places like Detroit and New York. It has to search for meaning in the African-diasporic connections that were forged in travels to Mexico, southern Africa, and the United Kingdom. Black Study occurred here as well. And Cedric saw in real, Black space and in communal time the ways in which structures of thought that sought to understand and make realizable certain outcomes for Black peoples were deeply, even fatally, flawed. It was a form of study that was with rather than simply of Black peoples, a way of realizing that managed to offer more than the scientific veneer of objectivity in favor of a sort of rigor and deep thinking that was grounded in solidarity. 22That mode of being with and for was necessarily a mode of being against the very structure of domination in even its most welcoming forms, and it inculcated a deep suspicion that Black people might be better off living, dying, and obtaining “freedom on their terms.” 23

This may indeed be a model for us in these ever dark times – this normal time of darkness. Thinking with Cedric and the contexts of his life then would reveal the particular sites of his epistemic rupture with western time and the premise of his quite prescient view that, at its heart, the Black Radical tradition was ultimately grounded in preserving the ontological totality of peoples whose lives were interdicted by the political and material requirements of the modern world and whose understanding of how to be free must now be our point of departure for thinking freedom. This is a text that exists to call attention to a life, and not merely narrate its details, in order that we do more than find in Cedric’s work a subject to study. For, in calling attention to a life, we call attention to ourselves. 24

Some believe now that western time is late, that capitalism is late. This idea of late capitalism is an attempt to name a moment where time had reached a moment of completion, a natural evolution toward an end – a teleological “end of history.” Yet what actually attended late capitalism was a further deepening, an entrenchment of a violent logic of othering and weaponized difference-making that has produced an assault on the commons, a sensibility that renders everyone and everything in and as a market relation, as the new common sense of how to be in the world. 25Cedric’s intellectual work appeared at perhaps a critical inflection point in the making of this neoliberal set of arrangements, as the 1980s saw the coming together of both the discursive and political logic that attempted to stabilize order through the twinned tactics described by Edwards as “incorporate and incarcerate; co-opt and incapacitate; represent and destroy.” 26

Those signs of the collapsing world that occasioned the words and vantage point in 1983 have been exacerbated, as the “racial regimes” that Cedric wrote of in 2007 are constantly updating themselves, as they must if they are to continue. 27Globally, the racist foundations of capitalism are evident; these “native racisms,” responsible for death on a massive scale, have produced a moment where simply saying “Black lives matter” becomes an attempt to stave off the disavowal of Black humanity. And even such declarations are met with further utterances of contempt. Underneath those utterances are affirmations of the modes of living and the temporal and spatial constructs that have generated a newly energized racial capitalism that is supported and reified by a white nationalist consciousness where everyone is vulnerable, every day. One could easily identify the election of the forty-fifth US president and the subsequent right-wing and fascist efflorescence, the turmoil in Europe, Africa, South and Central America around migration, permanent war, the global pandemic, and the increasing fears around human planetary existence as realities that make the current moment a prime one for an initial engagement or reassessment of Cedric’s work. And they would be correct. But western time has always produced the urgency we feel. It has never not been this late, this dark.

Black people, as Christina Sharpe has written, live in the wake of immanent and imminent death, which in the conception of western time is the erasure of life. We need Cedric Robinson’s work, then, for it reminds us that there are ways of inhabiting these conditions and finding ways not to be reduced to them; or, in Sharpe’s words, we need to find solace in “tracking the ways we resist, rupture, and disrupt that immanence and imminence.” 28We need Cedric Robinson’s work because what we need in this moment are better ways of seeing and marking the limits of a conceptual project that renders so many of those who have been marked for death as having no rhythms of human action to speak of, who have been prevented from offering what they know about (an)other time.

It was Cedric, again in 2013, who reminded us that Black modes of living in the forms of spirituals were often dismissed as “noise,” and that what was assumed as “noise” had evoked and invoked life. He told us to find that noise, to see the ways that this noise has been, at root, what we are. 29For beyond these ideas of death is the mode for the very reproduction of Life, which is, after all, a cycle.

1 1. This conversation about the Bakongo is based on the work of Tata Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, the Congolese intellectual who has contributed vastly to our understanding of Bakongo worldviews and their application to contemporary problems. See his African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Tying the Spiritual Knot: Principles of Life and Living (Athelia Henrietta Press, 2001), 35–8, for a discussion of the tuzingu and many of these other principles. For an anthropological perspective, see Wyatt MacGaffey, Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (University of Chicago Press, 1986).

Читать дальше