4 Chapter 4Figure 4.1. Actress Gloria Swanson in a publicity shot for the...Figure 4.2. Motion picture poster for the film Cabiria (1914)..

5 Chapter 5Figure 5.1. The Seven-headed animal from Metropolis (1927).Figure 5.2. The underground world of The Mole People (1956)...

6 Chapter 6Figure 6.1. Gate of Ishtar reconstructed at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. Figure 6.2. The Babylonian court of Intolerance (1916). Public domain.Figure 6.3. Poster for Noah’s Ark (1928). Public domain.

7 Chapter 7Figure 7.1. Le Festin de Balthazar, a film by Louis Feuillade..Figure 7.2. Assyrian banquet relief.Figure 7.3. David W. Griffith near Ishtar’s statue.

8 Chapter 8Figure 8.1. Blanche Sweet as Judith in Judith of Bethulia...Figure 8.2. Yvonne Furneaux as the Assyrian queen in Io Semiramide (1963).Figure 8.3. Scene from Intolerance (1916). Public domain.

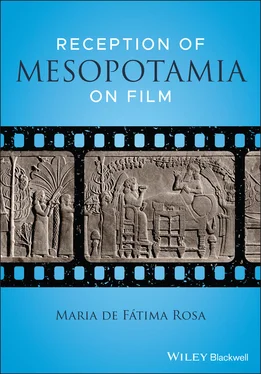

1 Cover

2 Title page Reception of Mesopotamia on Film Maria de Fátima Rosa NOVA University LisbonLisbon, Portugal

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Table of Contents

6 List of Abbreviations

7 Acknowledgements

8 Begin Reading

9 Bibliography

10 Index

11 End User License Agreement

1 i

2 ii

3 iii

4 iv

5 v

6 vi

7 vii

8 viii

9 ix

10 x

11 1

12 2

13 3

14 4

15 5

16 6

17 7

18 8

19 9

20 10

21 11

22 12

23 13

24 14

25 15

26 16

27 17

28 18

29 19

30 20

31 21

32 22

33 23

34 24

35 25

36 26

37 27

38 28

39 29

40 30

41 31

42 32

43 33

44 34

45 35

46 36

47 37

48 38

49 39

50 40

51 41

52 42

53 43

54 44

55 45

56 46

57 47

58 48

59 49

60 50

61 51

62 52

63 53

64 54

65 55

66 56

67 57

68 58

69 59

70 60

71 61

72 62

73 63

74 64

75 65

76 66

77 67

78 68

79 69

80 70

81 71

82 72

83 73

84 74

85 75

86 76

87 77

88 78

89 79

90 80

91 81

92 82

93 83

94 84

95 85

96 86

97 87

98 88

99 89

100 90

101 91

102 92

103 93

104 94

105 95

106 96

107 97

108 98

109 99

110 100

111 101

112 102

113 103

114 104

115 105

116 106

117 107

118 108

119 109

120 110

121 111

122 112

123 113

124 114

125 115

126 116

127 117

128 118

129 119

130 120

131 121

132 122

133 123

134 124

135 125

136 126

137 127

138 128

139 129

140 130

141 131

142 132

143 133

144 134

145 135

146 136

147 137

148 138

149 139

150 140

151 141

152 142

153 143

154 144

155 145

156 146

157 147

158 148

159 149

160 150

161 151

162 152

163 153

164 154

165 155

166 156

167 157

168 158

169 159

170 160

171 161

172 162

173 163

174 164

175 165

176 166

177 167

178 168

179 169

180 170

181 171

182 172

183 173

184 174

185 175

186 176

187 177

188 178

189 179

190 180

191 181

192 182

193 183

194 184

195 185

196 186

197 187

198 188

199 189

200 190

201 191

202 192

203 193

204 194

205 195

206 196

207 197

208 198

209 199

210 200

211 201

212 202

213 203

214 204

215 205

216 206

217 207

218 208

219 209

220 210

221 211

222 212

223 213

224 214

225 215

226 216

227 217

228 218

229 219

230 220

231 221

232 222

233 223

234 224

235 225

236 226

237 227

238 228

239 229

240 230

This book was carried out during 2020 and took shape while developing my postdoctoral project on Reception of Mesopotamian Antiquity at CHAM – Centre for the Humanities of NOVA School of Social Sciences and Humanities where I was awarded a grant (FCSH/CHAM/HIS/04666/1 BPD) through the strategic project sponsored by FCT (UID/HIS/04666/2013 and UID/HIS/04666/2019).

I am grateful for the support I received from colleagues who contributed with helpful ideas, providing advice, and above all by reviewing drafts of paragraphs or entire chapters. In particular, my gratitude goes to Isabel Gomes de Almeida for reading and commenting on the manuscript and to Carla Alferes Pinto for reviewing parts of the book. My thanks also go to Wiley’s editors Todd Green for the enthusiasm with which he welcomed the idea and Andrew Milton for his help and patience in answering all my questions. I would also like to thank Inês Pinto Coelho, Cristina Brito, Professors João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, Helena Trindade Lopes and specially Professor Francisco Caramelo, who encouraged the writing of this book from the start and conveyed me the fascination for ancient Mesopotamia.

For all the information and the stills provided, thanks are also due to several institutions: Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema, Deutsche Kinemathek - Museum für Film und Fernsehen, Gaumont-Pathé Archives, The Museum of Modern Art, The Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, WSM Art Metropolis in the person of Bertina Schulze-Mittendorff.

To my family, above all, I owe a debt of gratitude for all the support and encouragement. My last words go to my dearest niece, Mafalda, who has given me the motivation when I needed the most.

Introduction: Reception of Mesopotamia and the Cinema Lens

0.1 Reception Studies and Cinema

Studies on Reception of antiquity are relatively recent. Charles Martindale first included Reception Theory in the field of Classical Studies in 1993 with Redeeming the Text: Latin poetry and the hermeneutics of reception . The Professor of Latin from the University of Bristol was inspired by the research line inaugurated by the Constance School, with scholars such as Wolfgang Iser and especially Hans Robert Jauss, who, in the 1960s, boosted the field named Aesthetic of Reception. Jauss postulated that the observer of a work of art should be given an active role. In broad terms, he considered that the work of art was not a static or timeless phenomenon. 1In his own words, “A literary work is not an object that stands by itself and that offers the same view to each reader in each period. It is not a monument that monologically reveals its timeless essence. It is much more like an orchestration that strikes ever new resonances among its readers and that frees the text from the material of the words and brings it to a contemporary existence.” 2Martindale thus resorted to this seminal work to introduce new conceptions in the study of the Classics, claiming, like Jauss before him, that an author has no control over his work since it does not have an immutable meaning, always depending on the interpretations made about it and hence subjected to the cognitive role of the observer/reader, the “ active principle.” 3

To Martindale, the fact that reception presupposes the active participation of the reader, being himself an essential part in the relationship between present and the past and its prolific dialogue, 4differentiates it from other sorts of analyses. Indeed, reception contrasts with other concepts that can also be applied to the study of the past, although with different meanings and uses, that is: “tradition” and “appropriation.” If, in the first case, we speak of an almost passive acceptance of a legacy from the past, in the second we are perhaps faced with a rupture of dialogue, an apprehension that makes it almost impossible to shape and modify the reader’s sensitivity. Considering the involvement of the reader, reception therefore presents itself as a basis for the study and interpretation of the reason to why there is not a single reading for history. 5In fact, we must remind ourselves that neither the culture produced by past civilizations is dead nor its influence on the present is linear. 6One should not, therefore, succumb to the illusion of considering antiquity as stationary, since as an object of analysis it changes throughout time, from one generation to the other, and from researcher to researcher. 7In other words, Martindale assumes that the same historical vehicle, the same text , 8can be interpreted in different ways depending on the agent and on the time of that interpretation. Naturally, history, as much as it wants to find unique and stagnant readings, depends, in large part, on its observer, on its reader, and on the way his present contemplates that past . Jauss inclusively reminded us in his opus of the words of R.G. Collingwood, who “postulate, posed in his critique of the prevailing ideology of objectivity in history – History is nothing but the reenactment of past thought in the historian’s mind.” 9

Читать дальше