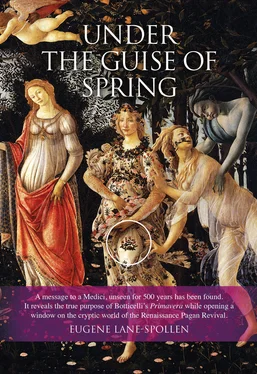

Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Under the Guise of Spring

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Under the Guise of Spring: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Under the Guise of Spring»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Under the Guise of Spring — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Under the Guise of Spring», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

* Ernst Gombrich, Gombrich on the Renaissance, 1985, p.41.

† John Shearman, ‘The Collections of the Younger Branch of the Medici’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 117, No. 862, 1975, pp.12 and 14-27.

The painting’s visual language, its great age and a Renaissance manner of thought foreign to our times, conceal its programme, and for many the total experience is as a consequence diminished.

Many different interpretations have battled for supremacy since the 1800s. In creating a painting of an apparently secular nature and on such a scale, Botticelli was breaking new ground. With an intuitive acuity Gombrich writes that ‘in their size and their seriousness, [the mythological paintings] vied with the religious art of the period.’ 1

The interpretations which have dominated the debate have fallen into three broad categories: the Neoplatonic; public parades and festivals (including the famous jousts and the romances of Lorenzo the Magnificent and his murdered brother); and ‘spring’ and the seasons (due in part to Vasari’s use of the words ‘Venus denoting spring’). This last connection prompted the suggestion of themes based on the classical figure of Venus and her role in springtime, with its associated customs, themes, colourful festivals and pageantry, which celebrate love and a new beginning in the season when all species reproduce themselves. 2Further theories are based on the Last Judgement, an astrological scheme, the judgement of Paris, a musical allegory, the enlightened age of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Pythagorean divine mathematics, the Medici and the return of the classical golden age, a Medicean political spring, an allegory of courtly love, and Venus and her entourage. One interpretation associates the months of spring and autumn with the eight adult figures in the painting. These figures have also been associated with the politics of the Italian states. It has also been proposed that the painting is an illustration of a mythological ballet popular at the time in Florence.

In 1940 Jean Seznec wrote of La Primavera: ‘ the ultimate secret has not yet been penetrated’. Speaking of Botticelli’s mythologies, he continued:

they conceal illusions of a personal and private nature ... with their air of remoteness and unreality of their setting. They transport us to another world ... to the Elysian fields among the Shades ... the great enigmas of Nature, Death and Resurrection seem to hover about these dreamlike forms of youth, love and beauty ... phantoms from an ideal Olympus. 3

La Primavera presents classical figures against the background of a verdant meadow carpeted with delicate and brightly coloured flowers, while oranges hang between the dark green foliage of the trees. Mercury, detached in mind and on the periphery, looks to the clouds just above his head. The Three Graces dance their circular dance with joined hands. One gazes at Mercury as Cupid is loosing his flaming arrow at her. On the right side, the wind god Zephyr bursts through the bay laurels in hot pursuit of the colourless wood nymph Chloris, from whose mouth issues a broken stem of flowers, 4while Flora strides forth, joyous and composed, onto a bed of some five hundred species of plants. Cornflowers, marigolds, violets and roses give voice, like everything in La Primavera, to a carefully composed message. What lies behind the look of Venus, who pointedly engages the young Medici ‘prince’ in whose private apartments the painting was placed for his private viewing? 5

The hidden meaning of La Primavera has been controversial ever since Botticelli found renewed appreciation in the late 1800s. Initially I was struck by its mood, and also by its very different rendering of spring, unlike any other in fifteenth-century Italian art. A serious, mystic and dignified tranquillity permeates its atmosphere, with each actor playing a role in a mise en scène to which admission is granted to those who speak the language, while at the same time, and unknown to them, excluding those not so privileged.

Primavera or spring is how the painting has been known. The absence of all the accepted symbols of spring other than flowers, which themselves had several alternative meanings in those times, is striking. Absent are the playful rabbits, swooping birds, manly shepherds and coy maidens accompanying ornate processions and floats, all heralding the joyful season of renewal, wooing, love, regeneration and the promise of plenty. In their stead, words like ‘sombre’ and ‘abstracted’ come to mind, capturing a mood which melds seamlessly with the undeniable sensuality of the classical figures, their poses and expressions. All is part of the painting’s intriguing contradiction, 6making it clever and challenging, as was expected of the artist. Certain elements observed, elements not at first obvious, hint at the patron’s intent.

1 Gombrich, Symbolic Images, 1985, p.32.

2 See Dempsey, The Portrayal of Love, 1992, p.88

3 Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods, 1961, p.113.

4 In classical mythology, Zephyr is the husband of Chloris whom he abducted and later married.

5 La Primavera was originally displayed with two other paintings (Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur and a large and very costly tondo of the Virgin and Child by an unidentified painter) in the ante-room (anticamera) to Lorenzo Minore’s main room. Following his death it was moved, together with The Birth of Venus, to the country house at Castello. See Appendix 1.

6 See Dempsey, op. cit., p.131.

3

A Very Private Location

THE LOCATION and occasion for commissions such as La Primavera tells us much. If it was a marriage painting (I will seek to show that it was), then a Medici wedding was an occasion of the greatest importance and one which would command a theme relevant to the parties to the marriage and reflective of the gravitas of the occasion. As one explores the enigma which is La Primavera, it is good to recall that nothing in Renaissance painting is ever present by chance.

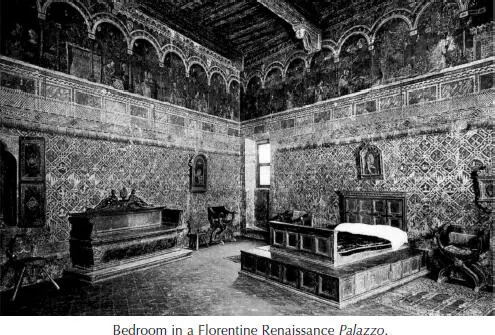

La Primavera was set above the backboard or spalliera of a day-bed which was placed against a wall in an ante-room to Lorenzo’s room or camera in his private apartments on the ground floor of the old town house or Casa Vecchia. 1 Members of the wider Medici clan, as was normal at the time, lived in close proximity to the principal palace. What Vasari saw seventy years later at the Medici Villa Castello in the Florentine foothills, like today’s viewer at the Uffizi, was a work of art removed from its original and intended context where it had a role to play and a relevance for the owner. Once removed to Castello, its function was purely decorative.

Personal apartments, whether for religious or lay people, could accommodate images considered inappropriate for public viewing. In anticipation of a landmark event such as a wedding, the master’s apartments in a patrician household were elaborately refurbished. This involved the introduction of paintings and painted furniture, the latter a fashion current in the hundred years prior to the 1480s. As we look at La Primavera we should remember that in a painting celebrating a marriage, traditional themes were presented to guide each party. Ancient stories were often adapted and made suitable for the whole household to see. 2While such panels often featured classical architecture and pagan figures, they were given a Christian gloss. They generally celebrated the families involved in the marriage through symbolism. Many included family crests and coats of arms, reminding the couple of the political importance of the union. 3The presence of such symbolism in La Primavera will be examined in Chapter 8.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Under the Guise of Spring» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.