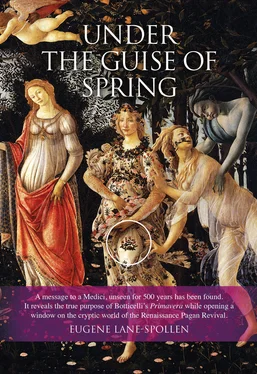

Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Under the Guise of Spring

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Under the Guise of Spring: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Under the Guise of Spring»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Under the Guise of Spring — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Under the Guise of Spring», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

7 Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods: Mythological Tradition in Renaissance .... 1972, p.137.

8 Godwin, op. cit., p.37.

9 François Rabelais (1495-1553), Gargantua and Pantagruel.

10 Dempsey, The Early Renaissance and Vernacular Culture, 2012, p.26.

11 Barbara Tuchman. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, 1978, p.xix. The great plague broke out in north-eastern China and killed two thirds of that country’s 8 million population in 1320. It spread to Genoa via the silk routes and by 1420 two thirds of Europe’s population, 80% in some cities, died of it. It took with it much of the artistic talent of the peninsula. (See also Kaborycha, A Short History of Renaisssance Italy, 2011, p.22.)

12 Valla’s skilful exposure was a triumph of Humanist research, argument and interpretation.

13 The Donation of Pippin and the document known as The Forged Decretals also contributed to the undermining of papal legitimacy. See Young, The Medici, p.259.

14 Sculpted images on the façades of buildings depicting devils devouring deviants had been commonplace since early medieval times. The façades of the cathedrals in Ferrara (1135) and Orvieto (1355) are examples.

15 Francesco Petrarca, Letters, 1372, Letter to Posterity.

16 Panofsky, Renaissance and Renaissances in Western Art, 1970, p.11.

17 Ancient Alexandria was the epicentre of the intellectual world with a manuscript collection in its library said to be in the order of 400,000 scrolls. Its accidental burning by Julius Caesar and its destruction in the sixth century by the Turks were among the greatest tragedies in the history of knowledge.

18 Stephen Kreis, ‘The Medieval Synthesis and the Discovery of Man’ (lecture), 2009.

19 Humanists generally favoured political neutrality as they had done in the era of Petrarch (1304-74) when the focus was on the discovery and translation of ancient manuscripts such as Plato’s Republic, which was translated from Greek into Latin by Francesco Filelfo (1398-1481).

20 Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 1990, p.121.

21 Seznec, op. cit., p.219.

22 Voss, Introduction to Marsilio Ficino, 2006.

23 Godwin, op. cit., pp.1-13.

24 This renewed urgency to reconcile differences was largely driven by the imminence of a Turkish invasion of Constantinople. Ferrara had been favoured with an influx of theologians, poets and philosophers, but an outbreak of plague there gave Cosimo an opportunity. Conscious of the prestige of hosting such an event, he offered Florence as an alternative venue. The change of location had a lasting effect on the intellectual development and consequent reputation of his city.

25 It would be two hundred years before the scientific discoveries of Copernicus and Kepler would fully validate much of what he maintained as true.

26 The Perennial Philosophy, also called Philosophia Perennis or Prisca Theologia. See Voss, Part 2, p.41 (Thesis, 1992), Gemistos and Cosimo.

27 Burckhardt, op. cit., p.145.

28 The transfer of the papal court to Avignon in 1309 had an immediate negative impact as Rome lost its most important employer. Rome, once an opulent city with a million people, packed with ambassadors and dignatories from all over the known world, had only 17,000 inhabitants by 1400 and was a wasteland, dangerous and lawless. Goats grazed among the ruins of the Forum as cardinals and their retinues picked their way through its toppled columns and fallen statues (see Godwin). Meanwhile, Florence had been rapidly transforming itself, growing in size and reputation as an artistic, commercial and intellectual powerhouse. With the return of the popes from Avignon, Papal authority was reasserted over a rising tide of heresies and Florentine artists were greatly in demand to promote the pope’s message. See Welch, Art in Renaissance Italy, p.241.

29 Seznec, op. cit., p.98.

30 Retractationes, 1, 13.3.

31 Snow-Smith, The Primavera of Sandro Botticelli: A Neoplatonic Interpretation, 1993, p.5.

32 Chastel, Art Ideas History, 1969, p.64.

33 Seznec, op. cit., p.99.

34 The concept of immortality was confirmed at the Lateran Council of 1513, fourteen years after the death of Ficino, presumably to counter the views of detractors such as Pomponazzi. See P.O. Kristeller, The Eight Philosophers of the Italian Renaissance, p.106.

2

Interpretations

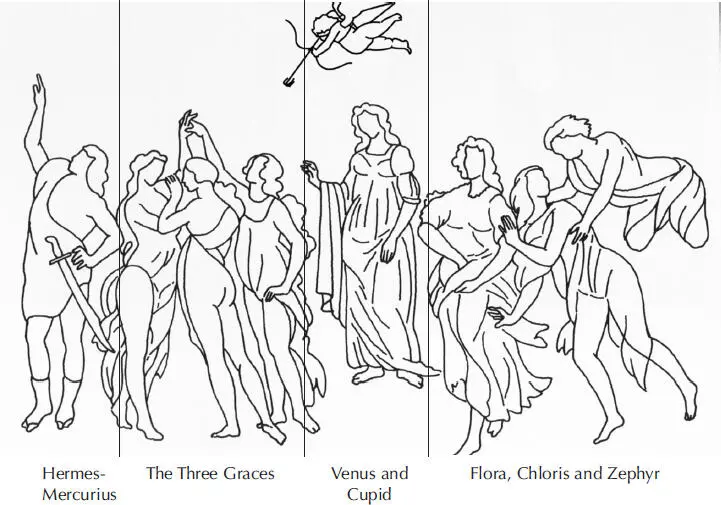

IT WILL BE SHOWN that the four distinctly different scenes above, each sufficiently complete to be separate paintings, appear to have little connection on a purely visual level. Unified by flowers, trees and a shared mystical ambiance, they have however an undeniable visual harmony. When the meaning of each emerges, we will see the four scenes unite seamlessly and unambiguously to show us what Lorenzo Minore would have seen and understood under his famous tutor’s guidance at the time of his marriage.

Adolph Gaspray in 1888 proposed a liaison between the poetry of Poliziano and La Primavera. Aby Warburg (1866-1929) developed this by drawing attention to the possible depiction of the courtly romance of the young Giuliano de’Medici and the beautiful Simonetta Cataneo. It has been suggested that the garden or meadow in La Primavera may represent the Elysian Fields or the afterworld where the murdered Giuliano and his beloved Simonetta are united in spirit.

In 1945 Sir Ernst Gombrich related the painting to a letter by Marsilio Ficino to Lorenzo Minore of the winter/spring of 1477/8.* He leans towards a Neoplatonic interpretation and cites the close consonance of the painting, primarily with the imagery of the Venus figure in Apuleius. Edgar Wind (1958) favoured a Neoplatonic interpretation. Frederick Hartt (1954) and Andre Chastel (1959) both favoured a Neoplatonic reading. Erwin Panofsky in 1960 gave a Neoplatonic interpretation which related La Primavera to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, based on their having been together at the Medici Villa Castello in 1515. He posited that they showed the two aspects of Venus, celestial and terrestrial. This thesis could not be sustained when John Shearman in 1975, analysing an inventory of 1498 taken on the death of Giovanni, Lorenzo Minore’s brother, discovered that La Primavera was in the old Medici town house in Florence, and not with the Birth of Venus at Castello.†

Ronald Lightbown in 1989 interpreted the Venus figure in the context of the marriage of Philology and Mercury (Martianus Capella) and casts Mercury as a guard over the garden dispelling intrusive clouds. Mirella Levi D’Ancona’s interpretation (NY, 1982) centres on the botanicals and proposes an allegory on a Medici marriage. Charles Dempsey, in The Portrayal of Love (1992), interpreted La Primavera in the context of the ten-month Roman agricultural calendar, Poliziano’s poetry, and the relationship between classical texts and Venus’ role in spring. Joanne Snow-Smith, in The Primavera of Sandro Botticelli (1993) proposed four levels of interpretation, one being the journey of the soul based on the Eleusinian Mysteries. Francis Ames-Lewis favours an interpretation rooted in the Laurentian culture of Florence – he holds it to be too sensual to carry a lofty interpretation. Charles Dempsey and Ronald Lightbown concur. Cristina Acidini Luchinat’s interpretation in Botticelli: Allegorie Mitologiche (Milan 2001) centres on the diplomatic triumph of Lorenzo the Magnificent at Naples and the consequent return to a spring of peace and renewed prosperity in Florence.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Under the Guise of Spring» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.