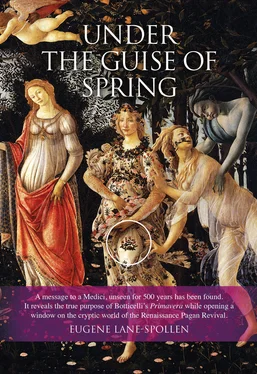

Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Under the Guise of Spring

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Under the Guise of Spring: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Under the Guise of Spring»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Under the Guise of Spring — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Under the Guise of Spring», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Academy and Ancient Truths

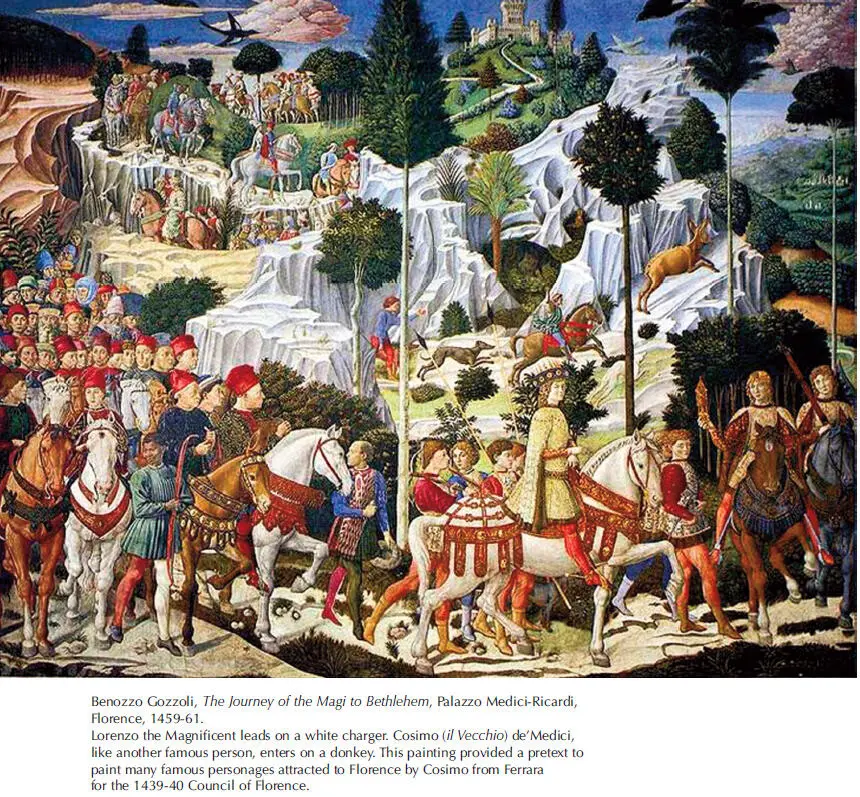

The coming together of a tightly knit group of intellectuals to form an ‘academy’ had its beginnings in discussions between Cosimo de’Medici the Elder, under whom Florence had become an artistic and intellectual powerhouse, and George Gemistos who arrived from Byzantium in 1437 as an emissary to the Council of Ferrara (1438-9). The Council sought to resolve the differences between the Eastern and Western churches. 24Gemistos was the foremost thinker of the last decades of Byzantium. In 1453 the city fell – but not before many precious documents were dispatched to Florence. His sea voyage was to prove fortuitous, because he travelled in the company of one of the most brilliant minds of the age, Cardinal Nicholas of Cues or Cusanus. 25On arrival in Florence, Gemistos expounded to Cosimo de’Medici the tenets of an ancient pre-Christian religion in which he perceived universal and ‘perennial truths’ known since the dawn of man’s capacity to wonder. 26These truths were compatible with Christianity because its Jewish founder held them inviolable. Cosimo was enthralled. Burckhardt acknowledged that ‘To Cosimo de’Medici belongs the special glory of recognising in the Platonic philosophy the fairest flower of the ancient world of thought.’ 27

The concepts were revolutionary. Central among them was the reconciliation of Judaism, Islam and Christianity, countering their evolution along parallel and opposing tracks. Twenty years later they were inspired by an antique document, the Corpus Hermeticum, believed to have been written by the Egyptian sage Hermes ‘Trismegistus’ (meaning the thrice greatest, god, priest and king) at the time of Moses. Its content was interpreted as confirming a single primal source of revelation and it became their basis for the pursuit of the reconciliation of which Gemistos had spoken. In 1463 Marsilio Ficino, who from that time led the Medici Platonic Academy, saw himself as the last in the line of sages and philosophers, starting with Hermes (known to the Egyptians as Thoth; Hermes-Mercurius to the Renaissance), followed over time by Zarathustra, Orpheus, Pythagoras and Plato, each of whom relayed the tenets of the ancient religion naturally inherent in the human species.

Florence had become a hothouse of intellectual pursuits and the fall of Athens, five years after Constantinople, added to the intake of learned men and Greek culture. Those arriving from Byzantium brought with them cortèges of huge black slaves, exotic costumes and extraordinary animals, and also the religious inheritance of the antique world. With the Turks at their backs, they were drawn to Medicean Florence, a community which welcomed them with alacrity.

Following the return of the papacy from Avignon, fifteenth-century Rome had to re-establish itself as an important centre for artists and intellectuals. 28Papal claims to temporal power however, and the employing of mercenary armies to expand the Papal States, fed the impatience of the Humanists for a return to a more christian Christianity. Seznec writes: ‘In the light of Neoplatonism, the Humanists discovered in mythology something other than and much greater than a concealed morality: they discovered religious teaching – the Christian doctrine itself.’ 29

The thing itself, res ipsa, which is now called the Christian religion, was with the ancients [erat apud antiques] and it was with the human race from the beginning to the time when Christ appeared in the flesh: from then on the true religion, which already existed, began to be called the Christian. (Augustine, 354-430 AD) 30

With the door thus ajar, the light of a pagan sun warmed the cold grey flagstones when they knelt. The ancient sources were accepted by the Church Fathers as presaging the coming of the new religion and were welcomed as its historical justification. 31In the Renaissance, pagan mythology became a vehicle for the expression of ancient concepts which were progressively Christianised. André Chastel, on the subject of using one subject to symbolise another, wrote, ‘The use of double meanings became a common practice, as natural in the handling of images as the devising of iconographic programmes’ 32Thus in the Renaissance a visual language expressive of a new manner of thinking served to span concepts and epochs. Fuelled by confirming interpretations of fable and mythology, the line between the two became indistinct to the point that ‘Christian dogma no longer seemed acceptable in anything but an allegorical sense.’ 33Christian and Platonic sources became interchangeable. When we come to decipher the figures in La Primavera, in particular the central figure who dominates it, this point will emerge as central.

Some progress in understanding La Primavera has been made, though we have no commissioning document or confirmed patron (see Appendix 2, page 173). One has to rely on a multitude of sources including the private correspondence of the scions of the Medici family, speeches, tax records, marriage documents, commercial contracts, the visual language of the time, religious symbolism, marriage culture, and the everyday metaphors in the writings of the Medici circle.

This inquiry will endeavour to show that La Primavera emerged from the circle around the owner and painter at a time charged with a mission for the fusion of the three Abrahamic religions validated by revelations in the rediscovered works of Hermes-Mercurius (Hermes/Mercury). The personages of Venus, Hermes and the esoteric Graces, and theories of love and immortality, were being eagerly absorbed and had become subjects for intense and spontaneous everyday interchange. 34

La Primavera was painted at a time when leadership in learning, art patronage, education and most aspects of society were already long in transition. Power continued to shift from the Church to an educated laity whose prosperity and consequent erudition and enlightenment were eclipsing the old heirarchy.

During the early 1480s, the time of La Primavera, the atmosphere in Florence was still largely undisturbed by religious extremism. Le fin de siècle would change all that. Centuries of tragic experience forged in the flames of intolerance continued to validate the need for prudence.

This long-established tradition of veiling the esoteric against intolerance stood protectively between La Primavera, which was intended only for the eyes of a young Medici and his close associates, and a general audience they termed profane.

The allegorical visual language in La Primavera arose from this prudent tradition. In the closing decade of the fifteenth century, apocalyptic sermons culminated in the purifying bonfires of the Dominican friar Savonarola. These purgings of vanities are said to have consumed works by great masters. After more than five hundred years, during which time works of art have drawn the attention of zealots of all stripes, this extraordinary and beautiful painting has preserved its mystical treasure under the guise of spring.

1 A respectful address in the absence of an official title.

2 James Hankins, From the New Athens to the New Jerusalem. (Botticelli’s Witness, Isabel Stewart Gardner Museum.)

3 Petrarch (1304-74) was the primary initiator of the recovery of Greek texts in his lifetime.

4 Godwin, The Pagan Dream of the Renaissance, 2002, p.3.

5 Panofsky, Studies in Iconology, 1965, p.187.

6 Cassirer et al., The Renaissance Philosophy of Man, 1967, p.3. See also P.O. Kristeller, Renaissance Thought and the Arts: Collected Essays, 1990, pp.1-15; refer also to Chapter 5.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Under the Guise of Spring» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.