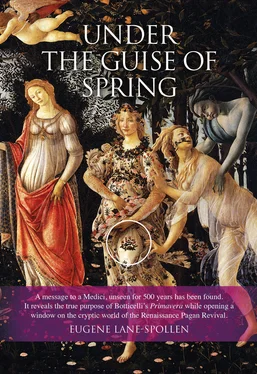

Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eugene - Lane Spollen - Under the Guise of Spring» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Under the Guise of Spring

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Under the Guise of Spring: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Under the Guise of Spring»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Under the Guise of Spring — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Under the Guise of Spring», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In similar vein, a Franciscan monk, whose words ‘shake with the laughter of the human soul’, wrote:

there ought to be no clock summoning the individual to their duties, no monks or nuns, nothing but fair women and handsome men are to be allowed into the abbey of Thelme. All should marry and all should be rich and live at liberty. 9

The sense of empowerment which took root is well represented by Leonardo da Vinci, a younger contemporary of Botticelli, who was the embodiment of the universal or Renaissance Man, free as a human god who acknowledged no bounds. In this atmosphere Marsilio Ficino championed a new Humanism empowering the individual: his ‘god within’ vision proved deeply attractive to the erudite in late medieval Florence, from where it rapidly spread to engage and uplift. All these elements, when combined with a renewed cultivation of the Tuscan vernacular and revival of the visual arts, represented their world in a new and uplifting light. 10

The feudal system and role of the old nobility, already long in decline prior to the Black Death (1348), were further weakened by the rise of banking, international trade and a developing urban competence in manufacture. The hold of the Church on society had remained largely unchallenged through medieval times, determining the rhythm of life through a pervasive involvement in all matters public and private. 11It lost some of its authority after its failure to protect the population from God’s wrath – perceived as the only possible explanation for the great plague. Further discredit came with the ostentation and worldliness of the Avignon papacy. An inability to fully convince the educated classes that the Church represented moral authority was compounded by its undisguised temporal ambitions, the misdeeds of corrupt and worldly members of the clergy, and the exposure of forgeries such as the Donation of Constantine which granted rights over Europe to the papacy. 12Ultimately these developments repelled and dispirited many, paving the road to the Reformation and the emergence of Protestant movements. 13

Art had served patrons and priests by presenting their message succinctly and memorably, impressing upon the faithful the rewards and penalties of the afterlife and teachings from the New Testament. Painted and sculpted images reinforced the status of the papacy as the single institution blessed by God to be his representative on earth. 14

Humanism

Petrarch (1304-74), a devout Christian, lent impetus to a growing sentiment when he described his age as dark and antiquity as enlightened: ‘Among the many subjects which interest me, I dwelt especially upon antiquity, for our own age has always repelled me.’ 15He felt that he was born too late among Christians who walked like a meandering herd in darkness. For him, the age after Roman emperors embraced Christianity was an age of decay and obscuration, and the pagan era, one of glory and light. 16

The classical era which so inspired him had been an age of inquiry and research, the pre-Christian centuries having produced great minds, inventions, and insights into science, astronomy, philosophy and much besides which shaped ancient society. Archimedes, Euclid, Aristotle, Plato, Pythagoras and Thales were just a few of those who had thrived in an atmosphere charged with inquiry. 17Under Petrarch’s influence and that of his successors, Florence had become captivated by the classical cultures of the Mediterranean basin, in particular those of Greece, Egypt and Rome. The Greeks, disillusioned with the unlikely stories surrounding their own gods, had sought more satisfying answers, and philosophy as a discipline was born. They put the physical, spiritual and intellectual abilities of the individual above all other considerations. Truth became their quest, and understanding ‘The Good’ and what it required of them, their goal. Individual responsibility was valued, as were individuals who could free themselves from the shackles of superstition and the ambitions of those who would control by fear. Classical architecture reflected this dignified Being, and artists celebrated his divine nature, recognised by philosophers since Plato. Erasmus (1469-1536) would suggest that the epithet ‘Saint’ should be attributed to Socrates and Cicero. 18Such ideas flourished among enlightened Florentines, for the ancient perceptions appealed, addressing unspoken concerns.

Cosimo de’Medici’s palace on Via Larga became a magnet for the Humanists. 19Under his influence, Humanism, which took man to be the measure of all things and had heretofore concerned itself with the individual’s responsibility to his society, altered course to emphasise the reconciliation of the Christian faith with the Hermetic religion of pre-Christian times. In seeking to make Italy’s classical past both relevant and enlightening, they embraced new concepts of religion, culture and society derived from the pre-Christian age. For the Medici circle, the two most influential figures were Hermes-Mercurius, who represented the divine word, and Plato, the last in a line of sages to pass on the torch of ancient wisdom. The members of this erudite group were nonetheless devout Christians who did not contemplate a challenge to the established religion. On the contrary, they sought to strengthen it, rendering it less vulnerable to a rising chorus of detractors.

Images and ideas spread rapidly, encompassing all fields of cultural activity. By the 1400s, and most notably its second half which is our focus, the infectious, empowering message had spread far beyond Florence’s refined salons. ‘From Italy it quickly advanced and became the breath of life for all the most instructed minds in Europe.’ 20Of this spreading interest, Seznec wrote: ‘The ancient poets were by this time in every hand. The Humanists drew their nourishment from Virgil and Ovid, profane bibles which they knew by heart.’ 21They sought to infuse their society with the perennial wisdom of the ancients, and through art seed its essence. 22

An Inspiring Horizon

Renaissance scholars looked to the horizon with an optimism born of their own liberation of mind and to a world of renewed possibilities with man at the helm. The ancient Pantheon, whose gods were like men, with strengths and very human passions, descended once again into a Christian society to inspire artists, expand horizons and grace the city’s palaces and gardens.

A stranger unfamiliar with the city might have been misled into believing that the citizenry had abandoned their faith in favour of the ancient deities, given the profusion of ancient and all’antica art. However, many Florentines saw no conflict between their own essential beliefs and philosophical traditions, which were widely accepted as pointing to the Christian ideal that they perceived as an evolution from a much more ancient tradition.

The educated elite embraced this patrimony with pride and passion. Ancient gods, heroes and muses appeared in pageants and plays, and artists were commissioned to embellish domestic surroundings, fountains, statues or pieces of furniture with representations of pagan subject matter. Expressions of the classical past presented themselves in many forms. It had long been the fashion for rulers and leading citizens to be buried in re-used ancient sarcophagi or in wall tombs that used a combination of ancient and Christian motifs.

In 1464 a group of painters including Mantegna explored Roman ruins at Lake Garda. So intoxicated were they by the classical mood that they called each other by classical names and Roman titles, wore laurel wreaths on their heads and rowed on the lake singing to the accompaniment of lutes. 23This acceptance of the classical within a Christian society is not difficult to understand given the pride which citizens felt in their ancient heritage. For the more erudite, little seemed to separate them from the famous men of classical antiquity. Petrarch wrote a letter to Cicero as if the Roman statesman had been living in a different city rather than a different era. Classical manuscripts were regarded as friends: Machiavelli dressed in his finest clothes to read them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Under the Guise of Spring» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Under the Guise of Spring» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.