and in part rule-based (geometry, orientation, local climatic factors), aimed at creating comfort and

reducing energy demand. Passive design had become marginalised in the 1970s and 1980s when the

ubiquitous skyscraper, sheathed in airtight skin and projecting an appearance of modernity, could be built

in any city, any climate. It was getting harder to make a case for permeable façades that would let in the

wind and light. Yeang's bioclimatic skyscraper attempted this and, in the process, offered a counterpoint

to the International Style. Spatially, the plan had passive- and climate-controlled spaces side by side;

in some spaces, occupants could toggle between the two. Parts of the building were surrendered to

semi-outdoor sky courts that formed an edge condition; service cores became thermal buffers to the

East–West sun; the plan and section were intersected with pathways for natural air movement; and the

facade was an arrangement of recesses and protuberances that mediated between indoor and outdoor.

These factors and features became emblems in Yeang's work in the 1980s and 1990s.

Yeang's current approach to the ecology of buildings came later and brought to this vocabulary

several emerging strands of science: ecosystem services (mimicry of nature's processes), ecosystem

habitats (greenery as pathway and patch), design metabolism (waste management and recycling), and

x FOREWORD

FOREWORD xi

biophilic design (human well-being). The edge was no longer indoor vs outdoor; it was human-built

systems interfacing with natural ecosystems. He argued for a synthesis of organic with the inorganic,

what he calls ‘biointegration’. Ecology, once confined to the ground, would be drawn up into built systems

to becoming part of the fabric of architecture.

In both his bioclimatic and ecological models, Yeang makes a case for ‘aesthetic exploration’, the

expression of elements and processes that he says are necessary to fulfil the aesthetic and biophilic

needs of users. The design vocabulary would articulate what elements do and how they connect with

each other. Form would shape performance and offer a perspective on beauty.

In his earlier book, Constructed Ecosystems, Yeang explains biointegration as the union of space,

technology, and surface, seeking new form-patterns. An eco-cell, for instance, cleans water and draws

air and light vertically through a building; the linked green wall is a planted facade, made continuous, to

enhance habitat formation and species movement. In one of his built examples, the Solaris (2011), a

17-storey office building in Singapore, a diagonal light-shaft cuts through the building's mass; multiple-

stepped landscape decks are connected to a 1.5 km spiral garden, through an eco-cell. No biodiversity

audit has been carried out, but there are anecdotal sightings of squirrels, snakes, and hornbills .

Yeang's goal is to restore the broken link between human and natural systems. Biointegration

makes architecture a ‘prosthetic’ to nature. This aligns Yeang with the eco-modernists who speak of the

hybridisation of the natural and human-made. His projects, even where they do not reach full potential,

are prototypes, he says, to refine ideas that ‘for the potency of what they promise’ challenge the design

profession at a time when the restoration of natural systems has a newly found urgency.

Nirmal Kishnani (Dr.)

Associate Professor, School of Design and Environment,

National University of Singapore

Excerpt from ‘Ecopuncture, Transforming Architecture and Urbanism in Asia’, a 2019 book by Nirmal Kishnani, published by BCI Asia

Construction Information Pte Ltd.

xii INTRODUCTION

Introduction

The publication of this book on ecological architecture comes at an unprecedented

time, as humanity’s impact on the environment has never been so significant. We sit

at a crossroads in our relationship with climate change. The UN Secretary-General

warned in 2018 that life on Earth faced a ‘direct existential threat’ if global warming

is not kept under 1.5°C, whilst the Members of Parliament in the United Kingdom

have declared an ‘Environment and Climate Emergency’ amidst an ongoing series

of protests by the group calling itself Extinction Rebellion. It is increasingly apparent

that the air we breathe, the water we drink, the earth we plant in, the food we eat,

and − crucially − the overall integration of our natural and built environments have all

been compromised. This can arguably be largely attributed to decades of governments

marginalising environmental policies and societies undervaluing ecological designs.

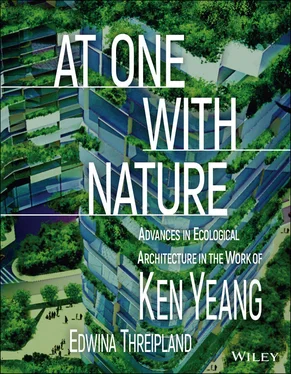

In this context, Ken Yeang’s prescience as an architect is impressive and highly

judicious; his doctorate in the early 1970s was titled, ‘Theoretical Framework for

the Ecological Design and Planning of the Built Environment’. This topic drove his

dissertation (which was agreed with John Meunier, then Head of Graduate Studies at

Cambridge University) and became his life‘s agenda when he started a practice. We

share some academic lineage, both of us having been students at the Department of

Architecture there, influenced by many of the same minds from the faculty, such as

Professor Marcial Echenique (who became head of the Department), Dr. Dean Hawkes

(who left to become Professor at the School of Architecture at Cardiff University), and

Peter Carl.

After university, Ken continued to further pursue and develop his work on ecological

design on both theoretical and practical levels. He developed a model framework through

the biological integration of sets of ecoinfrastructures, namely natural, technological,

water management, hydrology systems, and societal factors. In practice, he was able

to interpret this abstract theory into physical forms through his architecture and his

masterplans, and his built projects from over 40 years ago and was already looking at

ways to integrate designed systems more benignly with nature. Through both passive

and controlled methods of reducing energy demands, he has for decades looked at

making buildings and communities run as complete ecosystems, with minimal external

energy supply. It is evident that developing those theoretical subsystems is integral to

making his architectural designs fully credible.

INTRODUCTION xiii

xiv INTRODUCTION

His most recent work – which is explored in this book – has honed that rigorous

research towards architecture specifically mimicking nature’s processes. He now

integrates the human-made with the landscape completely, because his current theoretical

work is on ‘ecomimesis’ – the idea of designing by emulating and replicating by design

the attributes in nature’s ecosystems. He is among the few architects whose built work

Читать дальше