THE WORD “GOATS” ENDED IN A SQUEAK

THE WORD “GOATS” ENDED IN A SQUEAK

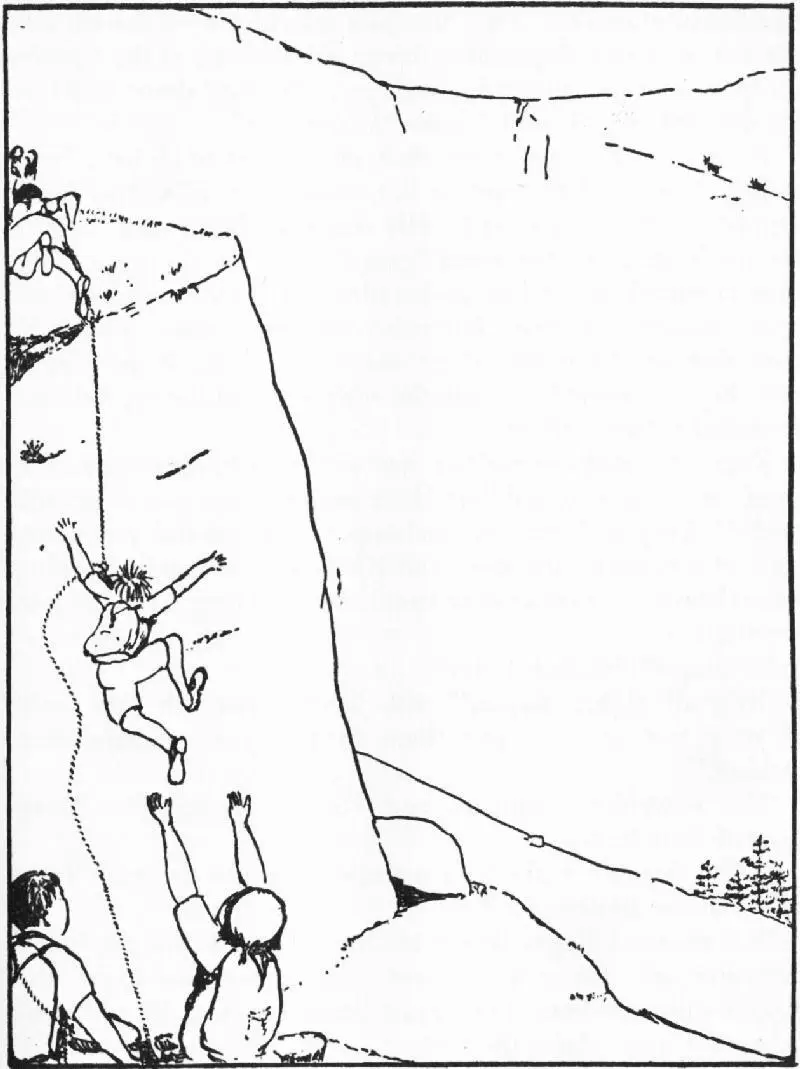

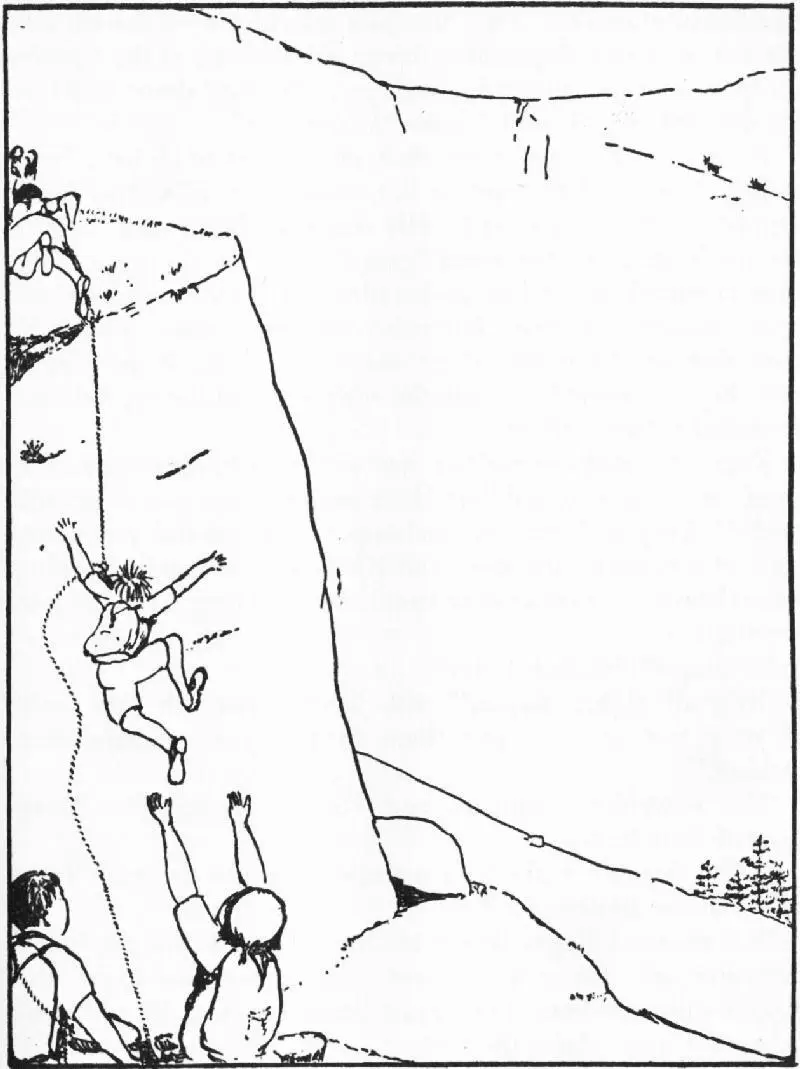

If he had done no more than shout all would have been well, but he tried to point at the same time. His other hand slipped. He swung round. His feet lost their places on the narrow ledges, and the word “goats” ended in a squeak. The rope tautened with a jerk and pulled Titty back half over the edge. Susan and even Nancy herself were almost jerked off their feet on the grassy slope above the rock. It was lucky that they had moved on from the edge and had the rope almost stretched between them.

Roger dangled against the face of the rock, about four feet from the bottom, scrabbling like a spider at the end of his silk thread. Titty had grabbed a clump of heather and was being held where she was by Susan and Nancy who were now hanging on to the rope as hard as they could, and had dug their feet into the slope.

“Pull, pull!” called Titty.

“It’s all right, Roger,” said John. “Let me have hold of your feet and I’ll put them in the good places. Stop kicking.”

The scrabbling stopped, and Roger felt his feet being planted from below.

“Now then, start climbing again, or you’ll be bringing Titty down on the top of you.”

The moment Roger began to climb, he took his weight off the rope and Nancy and Susan pulling together found the weight suddenly less. Titty came head first over the edge and up on the grass above the rock.

“Keep on pulling,” she panted, “or he may go flop again. But don’t pull too hard.” She crawled on as well as she could. She had had much the worst of it, and had scratched her elbows and knees slipping back over the edge of the rock.

Roger’s voice came cheerfully from below.

“Did you see the goats?”

“Never mind goats,” called Susan from above. “Is he hurt?”

“Only another scrape,” said Roger. “But did you see the goats? There they are again.”

“Don’t point!” shouted John, just in time.

“I must,” said Roger. But he didn’t. “There! There! You’ll see them again in a minute. There they go. Right up by the top.”

The topmost peak of Kanchenjunga was directly above the explorers. But to the right of it, as they looked up, the huge shoulders of the mountain, lower than the peak itself but high in the sky above them, swept round to the north, and it was up there, almost behind the explorers, that Roger, looking over his shoulder as he climbed, had seen things moving on the grey stone slopes under the top of the crags. Up and up they were going, now close under the skyline. Just as John and Peggy caught sight of them they crossed the skyline itself, tiny, dark things, goats cut out of black cardboard against the pale blue of the morning sky.

“I see them,” called Titty.

“Five,” said John.

“There’s one more,” said Roger.

A moment later they were gone.

“Well, I’m glad we’ve seen them,” said Roger.

“Get on up to the top of the rock,” said John. “And don’t look for any more. If it hadn’t been for Titty and the others hanging on to the rope you might have broken your leg.”

“And no stretcher to carry me on.”

Roger hurried up with his climbing and was soon on the grass slope above the rock, being looked over by Susan. Neither she nor Nancy had seen the wild goats, so naturally they thought more about the accident.

“Shiver my timbers,” said Nancy, “but that was a narrow go. We really ought to have waited at the top, taking in rope hand over hand so that he couldn’t slip. But you can’t allow for everything. Who would have thought of his seeing goats just at that moment? If they were goats. Probably sheep.”

“They were goats all right,” said Peggy, climbing up. “We all saw them.”

“All right,” said Nancy. “Goats. But not such goats as some people I know. What about you, Able-seaman? Are you hurt too?”

Titty had been trying to lick the blood off her right elbow, but had found that she could not reach it, and anyway it wasn’t really bleeding enough to matter.

“Lucky it was Roger who fell and not John,” said Nancy. “Not so heavy, for one thing, and if it had been John, what would have become of the grog?”

They were more careful after that, and there were no more accidents. The last few yards up to the top of the peak were easy going. The explorers met and crossed the rough path that they might have followed from the bottom, and then, with the cairn that marked the summit now in full view before them, they wriggled out of the loops in the rope and raced for it. John and Nancy reached the cairn almost together. Roger and Titty came next. Mate Susan had stopped to coil the rope, and Mate Peggy had waited to help her to carry it.

All this time the explorers had been climbing up the northern side of the peak of Kanchenjunga. The huge shoulder of the mountain had shut out from them everything that there was to the west. As they climbed, other hills in the distance seemed to be climbing too, and, when they looked back into the valley they had left, it seemed so small that they could hardly believe that there had been room to row a boat along that bright thread in the meadows that they knew was the river. But it was not until that last rush to the top, not until they were actually standing by the cairn that marked the highest point of Kanchenjunga, that they could see what lay beyond the mountain.

Then indeed they knew that they were on the roof of the world.

Far, far away, beyond range after range of low hills, the land ended and the sea began, the real sea, blue water stretching on and on until it met the sky. There were white specks of sailing ships, coasting schooners, probably, and little black plumes of smoke showed steamers on their way to Ireland or on their way back or working up or down between Liverpool and the Clyde. And forty miles away or more there was a short dark line on the blue field of the sea. “Due west from here,” said John, looking at the compass in his hand. “It’s the Isle of Man.”

“Look back the other way,” said Peggy.

“You can see right into Scotland,” said Nancy. “Those hills over there are the other side of the Solway Firth.”

“And there’s Scawfell, and Skiddaw, and that’s Helvellyn, and the pointed one’s Ill Bell, and there’s High Street, where the Ancient Britons had a road along the top of the mountains.”

“Where’s Carlisle?” asked Titty. “It must be somewhere over there.”

“How do you know?” asked Nancy.

“ ‘And the red glare on Skiddaw woke the burghers of Carlisle.’ Probably in those days they didn’t have blinds in bedroom windows.”

“We know that one, too,” said Peggy. “But not all of it. It’s worse than ‘Casabianca.’ ”

“I like it because of the beacons,” said Titty.

John and Roger had no eyes for mountains while they could see blue water and ships, however far away.

“If we went on and on, beyond the Isle of Man, what would we come to?” asked Roger.

“Ireland, I think,” said John, “and then probably America. . . .”

“And if we still went on?”

“Then there’d be the Pacific and China.”

“And then?”

John thought for a minute. “There’d be all Asia and then all Europe and then there’d be the North Sea and then we’d be coming up the other side of those hills.” He looked back towards the hills beyond Rio and the hills beyond them, and the hills beyond them again, stretching away, fold upon fold, into the east.

“Then we’d have gone all round the world.”

“Of course.”

Читать дальше

THE WORD “GOATS” ENDED IN A SQUEAK

THE WORD “GOATS” ENDED IN A SQUEAK