The able-seaman moved crabwise, and not so fast, all the time looking over her shoulder to see that the four firs looked as nearly as possible like one.

They crossed the broad belt of heather and had already left the four firs far behind when Roger found the first of the pine-cones.

“Good,” said the able-seaman. “I was beginning to think we’d missed it.” She had another look back at the firs, and then hurried forward. She was picking up the second pine-cone before the boy saw it.

“Hurrah,” shouted the boy. “They’re the best patterans that ever were. We can’t miss the way now.” He galloped on over the moor and presently picked up the third.

“Shall we leave them for another time?” he said.

“No. Better throw them away. We don’t want to show anybody else the way to Swallowdale.”

“Which of us can throw farthest?” said the boy, giving Titty a pine-cone and running on to pick up another for himself.

The able-seaman knew that Roger could beat her at throwing, but she threw her pine-cone none the less. Roger threw his but not quite in the same direction, so they had to measure the distances by stepping before they could be sure that his had really gone a yard or two farther than hers.

“This is waste of time,” said the able-seaman. “Besides, Peter Duck could throw yards farther than either of us if he wanted to.”

They hurried on again, picking up the pine-cones one by one as they found them, and throwing each one away as soon as they saw the next.

They were high up on the top of the open moorland and had already long lost sight of the four firs, when Roger stopped suddenly and said, “What’s become of the hills?”

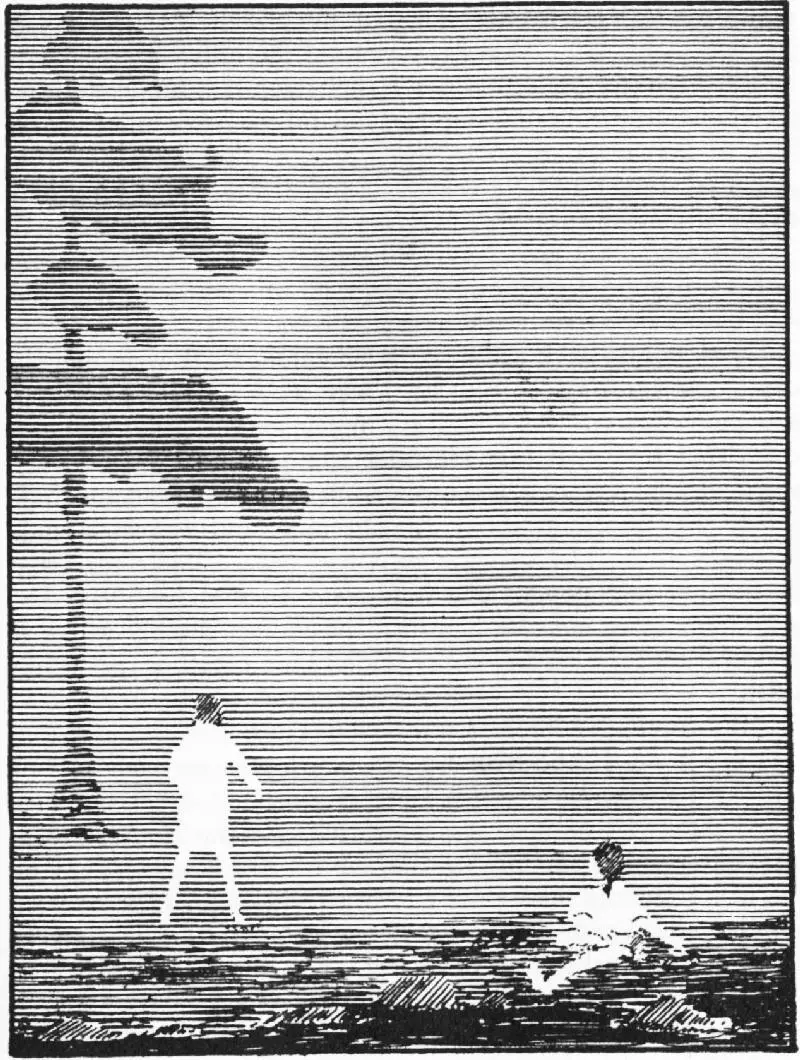

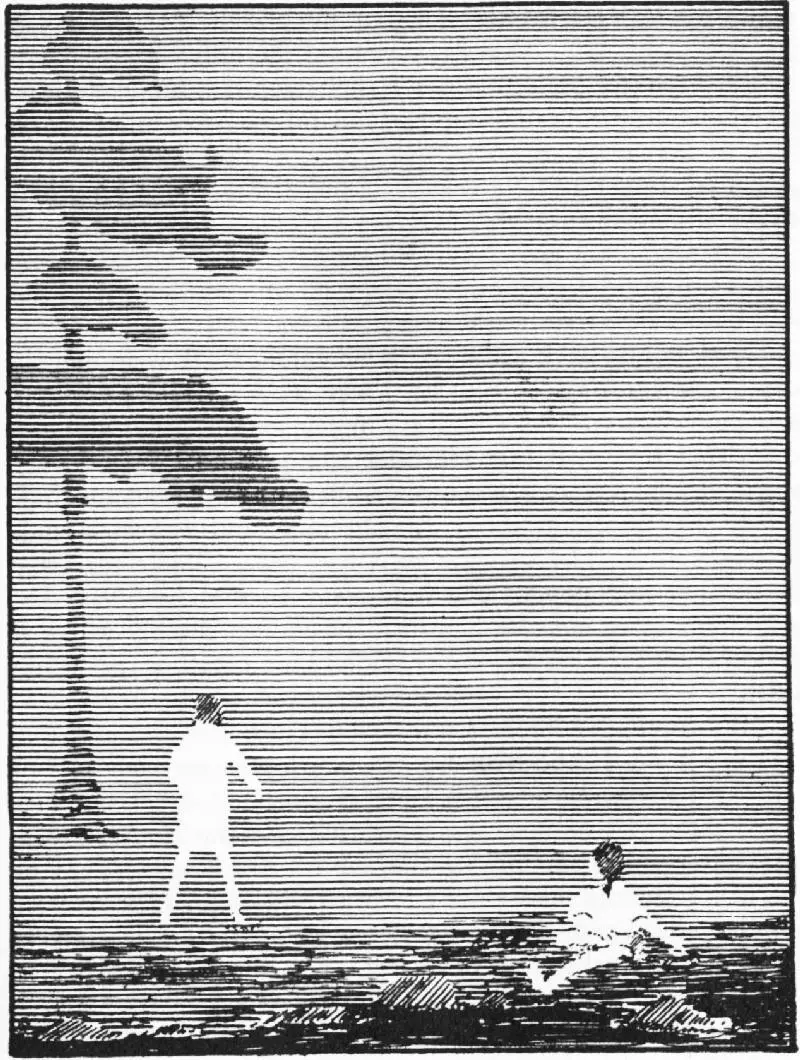

IN THE FOG

IN THE FOG

Titty looked back towards Kanchenjunga. Kanchenjunga stood out clear in the sunshine and so did the great hills beyond him to the north, but the lower hills to the south had disappeared altogether. It was as if there was nothing beyond the moorland but the sky.

“It’s not so hot now,” said Roger.

It certainly did seem much cooler all of a sudden. And the sunshine was not so bright as it had been.

Titty looked back again to Kanchenjunga. A wisp of pale cloud was floating across his lower slopes. His head was somehow fading. She could no longer see the peak with the cairn that they had that morning climbed. She looked over the moorland towards Swallowdale. Something was happening. There was no doubt about it. The moorland was shrinking. It was nothing like so wide as it had been. The trees away to the left had gone. The hills away to the right had disappeared. The moorland, instead of ending sharply where it dropped into the farther valley, faded into a wall of soft white mist.

“It’s coming in like the tide,” said Titty.

“We’re on a cape with the sea pouring in on each side of us,” said Roger.

A high wall of mist was now rolling towards them from the south along the top of the ridge. There seemed to be no wind, but the mist moved forward, little clouds sometimes spilling ahead of it like the small waves racing up the sands in front of the breakers.

“It’s cold,” said the boy.

“Let’s hurry,” said the able-seaman.

And then the mist rolled over the top of them and they could see only a few yards ahead.

“It wasn’t a cape,” said Roger. “Only a sandbank. And now the sea’s gone over the top of it.”

Titty sniffed and coughed.

“It’s sea-fog,” she said. “The tickling sort. Don’t breathe it more than you can help.”

“There’s a pine-cone somewhere close here,” said Roger. “I saw it a minute ago.”

He ran on a yard or two and was gone in the white mist.

“Roger.”

“Hullo!”

“Where are you?”

“Here.”

“Don’t move. Where are you now?”

“Here. Where are you?”

“Keep still. I’m just coming. Good. I can see you. That’s all right.”

“I can’t find that pine-cone.”

“Don’t run on again, anyhow,” said Titty. “We must stick together or we’ll lose each other. The fog’ll blow over.”

“Your hair’s all over dew.”

“I wonder if they’ve got it like this on the lake.”

“Shall I make a fog signal?” said the boy. “I will.”

“There’s no one to hear it.”

“I will, anyway,” said the boy, and a few damp sheep up on the top of the moor were startled by hearing what they did not know was the deep hooting of an Atlantic liner feeling the way towards Plymouth in a Channel fog.

“Don’t,” said Titty in a minute or two. “I want to think.”

Roger sent one more long booming hoot into the fog, and stopped.

“Nobody’s going to run us down for a minute or two,” he said.

“We ought to be able to find the next pine-cone. Keep fairly close to me and we’ll look for it. We shan’t be able to cover much of the ground if we’re very close together, but if we try going far apart one of us’ll get lost.”

“If one of us is lost both of us are,” said Roger. “Because if the one that was lost could see the one that wasn’t lost then neither of them would be lost, and if the one that was lost couldn’t see the one that wasn’t lost, then that one would be lost, too, as well as the one that it couldn’t see.”

“Oh, shut up, Roger. Do. Just for a minute.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” said the boy; and, a moment later, “may I say something?”

“What is it?”

“Here’s the pine-cone.”

“Good,” said the able-seaman. “Now you see the use of patterans. We’ll be able to find our way to Swallowdale in spite of the fog.”

“How will they manage on the lake?”

“With the compass. Oh, we’ve got it. But probably Captain Nancy has one of her own.”

Titty pulled the compass out of her knapsack and opened it.

“The black end points north,” she said, “so the white end points south. And south is where we have to go to find the next patteran.”

She held the compass before her, looking down into it and moving slowly ahead.

Roger, who had been keeping close to her, searching the ground, presently pulled at her sleeve.

“We’ve probably passed it,” he said.

The trouble was that Titty thought so too, but there was no way of knowing. The compass did not seem to help. This part of the moor was covered with short grass with patches of bracken and rocks and loose stones, and stones not quite so loose, bedded in the ground, with ants’ nests under them, if you lifted them. Here and there were thin tufts of dark green rushes, the sort of green rushes that are white when peeled and can be made into rings and plaits and even baskets. There was no track that anyone could have seen even if there had been no fog. Here and there were the sheep runs, but they ran all ways, and mostly from side to side of the moor and not straight along the top. It was very puzzling.

“You stand still,” said Titty, “and I’ll walk round in sight of you and look for the next patteran.”

That let her look all over a circle of a dozen yards across. But when she had worked all round it she was no better off.

“Now you stand still, and I’ll hunt,” said the boy, but he was no luckier.

“The only thing to do is to go on,” said Titty at last. “We must get home, because of Polly. And Susan said, ‘Get the fire going,’ too.”

She held the compass close in front of her and moved forward with her eyes fixed on the needle. The needle swung to and fro, no matter how steadily she held it, and the worst came to the worst when she caught her foot in a tussock of lank grass and fell on her face. The compass did not touch the ground. She saved it by letting herself fall anyhow, without trying to put out her hands. After all, the compass mattered most, so she kept it in the air, though she hit the ground herself much harder than she thought possible.

Читать дальше

IN THE FOG

IN THE FOG