“Where’s your can?” he said. “Mother says you’re to have it filled for you.”

Susan had washed out the can and now gave it to the small boy. He put it on the ground, filled it to the very brim out of his big can, ran his finger round the edge where some milk had slopped over, licked his finger and was just starting back when he seemed to change his mind. He put his can down, turned round and put both hands in his pockets.

“Where be you going?” he asked. “Up the beck?”

“Yes,” said Susan.

“Foxes up there,” he said. “Bite you. I’m not afraid of them.”

“Neither are we,” said Roger.

“Eight lambs they took, and eighteen fat pullets. Ask my dad.”

“Jacky,” a loud call sounded through the trees, followed by a louder, “Jackee!”

The small boy winked, picked up his can, said, “Happen I’d best be going,” and went slowly off again into the wood.

“Oh, bother,” said Roger a minute later, “I never asked him about the goats.”

“Never mind about the goats,” said John. “Shoulder packs. We can be getting on. All right, Susan, I’ll take the milk.”

Two minutes later the explorers were once more on the march.

Almost at once they began to climb. This stream hurrying down from Kanchenjunga fell far more steeply than the little beck that had led the able-seaman and the boy to the discovery of Swallowdale. It dropped sometimes ten, twenty feet at a time into pools from which the white foam spirted high in air to meet it. The explorers were glad they had no sticks to hamper them. They were glad to use their hands to cling to rock or tree as they pulled their way up. Careful as he was, John spilt a little of the milk, not more than a drop or two, but enough to show that anybody else would have spilt a lot. Sometimes they caught a glimpse of a path not far away, but remembering what Nancy Blackett expected of them, they took no notice of it whatever.

The evening sun shone down through the trees above them. It would soon be hidden behind the shoulder of the mountain, but when they looked back from high in the wood, they looked through the tops of pine and dark fir to broad sunlit country already far away. The hills beyond Rio now showed over the Swallowdale moors, and beyond those hills they could see hills more distant still, faint and blue, like clouds that had borrowed colour from the sky.

On and on they climbed, and came suddenly out of the trees into a ravine of naked stone and heather. They stopped short. The sun had that moment sunk behind the mountain above them, but it still lit the tops of the pine trees they had left. Presently these, too, were in shadow, though for some time yet the explorers, looking back, could see bright sunshine on the distant hills. To the left the peak of Kanchenjunga rose above the lesser crags that curved about the head of the ravine. Far up among those crags they could see thin white lines where the becks were still carrying off the water collected on the tops. To right and left of them were rough fells through which it seemed that the little stream at their feet had carved a channel fit for a river a thousand times bigger than itself.

“Isn’t he a beauty?” said Titty.

“Who?” said Roger.

“Kanchenjunga, of course. He’s the finest mountain in the world. I say, Susan, let’s put our things down, and run up just this little bit so that we can look out over the trees.”

“Go ahead,” said Susan. “I suppose this is the place for the camp?”

“It must be,” said John, and putting down milk-can and knapsacks they climbed the side of the ravine and then, resting, looked back once more, out of the shadow, over the sunlit country far away.

“You can’t see Rio,” said Titty. “I thought perhaps you could. But we’ll be able to see it from the top.”

“Hullo,” said John. “Let’s have the telescope.” Titty had brought it up in hopes of seeing Holly Howe. She gave it to John, who looked through it, not at the distant country but at the Swallowdale moors. He had seen, even without the telescope, the grey blob of the watch-tower. Everybody looked at it in turn. There was the rock, and the dark patch of water in the middle of the heather that they knew was Trout Tarn. Just beyond the rock must be Swallowdale itself. Titty thought of the parrot and Peter Duck taking care of the cave. “I expect they’ll be quite all right,” she said.

“Who?” said John.

“Polly and Peter Duck. They’ll be keeping each other company, just like mother and Bridget. Bridget’ll be in bed. It’s a pity we aren’t a little bit higher, so that mother could see our fire.”

“We’d better be making it,” said Susan, “and getting bracken or heather for beds before it’s dark.”

They gathered fallen branches in the top of the wood and cut a lot of bracken to make a soft place for their sleeping-bags. Then, while Susan was boiling some water over the camp fire, John opened a tin of pemmican, and the explorers had a simple and well-earned supper, just a scrap of pemmican for each of them, and some bunloaf after it, and a bit of chocolate, while the expedition’s one mug was refilled again and again with milk and a little tea and went round and round like a loving-cup.

Very soon after supper Susan blew her mate’s whistle, two short puffs and a long one, which means, “You are standing into danger, so look out.” Titty and Roger, who had been doing a little exploring in the dusk, knew what it meant and came running back to the camp where the fire was already beginning to look like a night fire, more flame than smoke, instead of like a day fire, which, in bright sunlight, often looks as if it has no flames at all.

“What danger?” asked Roger eagerly.

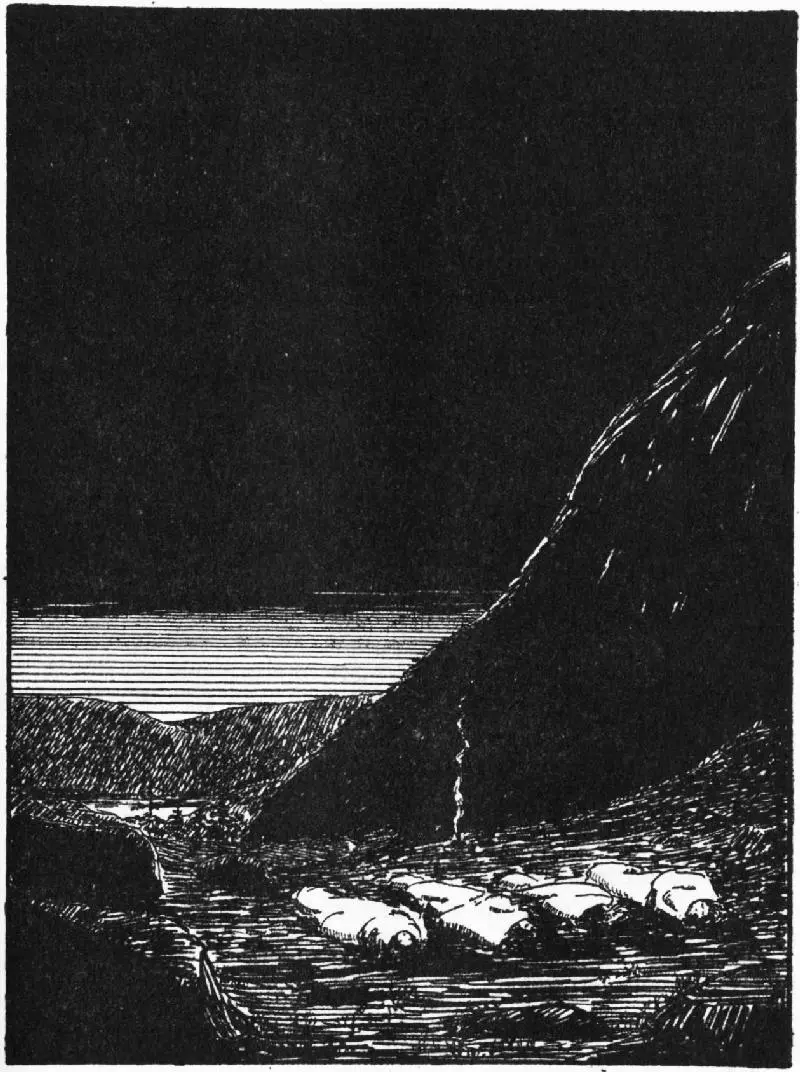

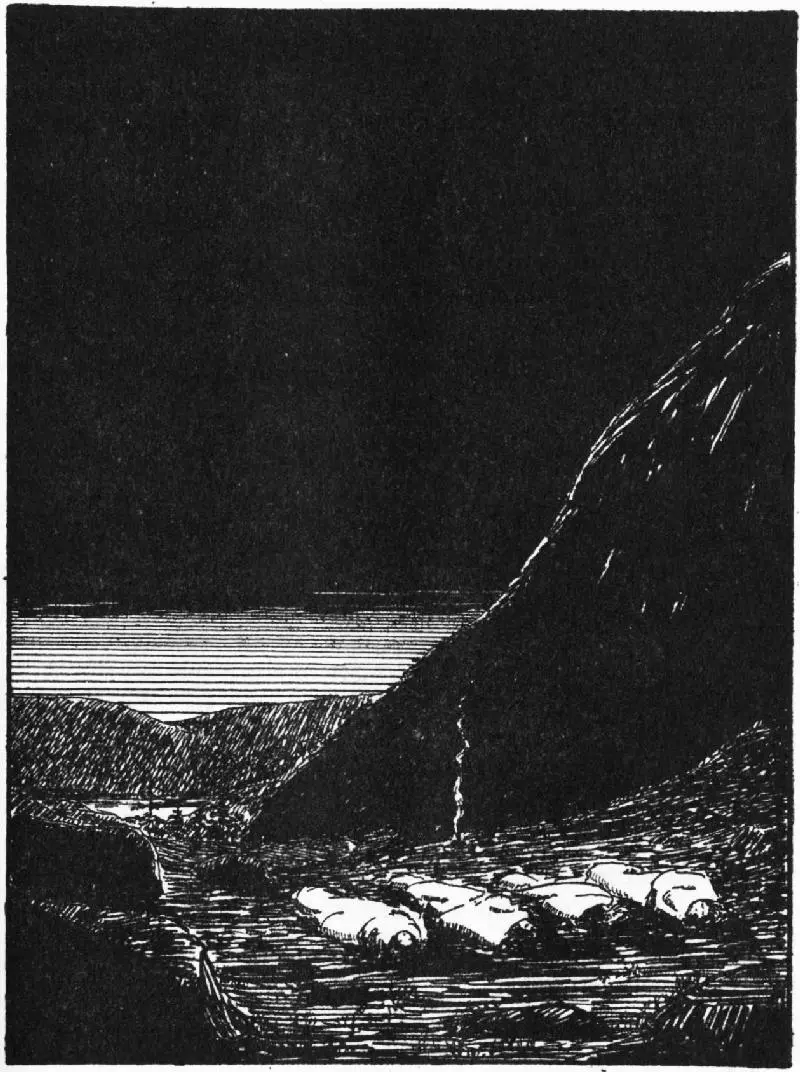

NIGHT ON THE MOUNTAIN

NIGHT ON THE MOUNTAIN

“Getting into trouble for going late to bed,” said Susan. “Hop in and go under.”

Titty was in her sleeping-bag in a moment. It was the first time in her life that she had ever slept half-way up a mountain and she did not want to waste a minute of it.

“It feels very naked going to bed without a tent,” said Roger.

“It’s all right,” said John. “I tried it last night.”

“Do I go under clothes and all?”

“Clothes and all,” said the mate, “and hurry up.”

“Where are you going to be? And John?”

“Close to you.”

“Near enough to touch?”

“Yes. But don’t do any touching when we’ve got to sleep.”

“Not even if the foxes come nosing round, like that boy said.”

“Not for anything short of bears,” said John, “and there are no bears. Remember you’re going to climb the peak to-morrow.”

“What am I to think about to get to sleep quickly?”

“Count the feathers in the ship’s parrot,” said Titty. “It’s much worse for him, poor dear, in the cave. It’s as if he’d had his cover on all day.”

Roger snuggled down in his bag. The stuffing in the bags was better than nothing, and with the bracken underneath he was comfortable enough.

“Who’s going to keep watch?” said Titty hopefully.

“Not you,” said the mate. “Go under and see if you can get to sleep before Roger. . . . If anybody wants a hot bottle,” she added presently, “I could put a hot stone from the fire at the foot of their sleeping-bag.”

“I’m as hot as anything,” said Titty.

There was no answer from Roger.

“Lucky there’s no wind,” said the mate.

“It’s almost stuffy,” said John.

For some time he and the mate sat by the camp fire.

“So long as they’re warm I suppose it’s all right,” said the mate at last.

Читать дальше

NIGHT ON THE MOUNTAIN

NIGHT ON THE MOUNTAIN