“Oh, nothing,” said Titty. “But do go on about ‘Casabianca.’ ”

“Coming to that,” said Nancy. “Do shut up, Peggy, just for a minute. You see, the whole thing is, she’s going away to-morrow. . . .”

“Not really?” said John, suddenly resting on his oars.

“Yes. But do keep on rowing. We’ve got a long way to go before we’re safe. She’s going to-morrow. We shan’t see her again till next year. Perhaps not then, if only she comes in term-time.”

“Hurrah!” shouted Roger.

“Sh!” said Susan.

“She wanted us to be made to drive round with her this afternoon to pay her farewell calls. Just when everything was working out beautifully. We’d sent the message with the arrow, and got out last night and hid the boat under the oak, and we’d told cook about your coming, and she’d made us enough grog to drown an admiral and crammed this basket full of grub and hung it up behind the back door so that we could swipe it without her having to know. Somehow or other the G.A. guessed that we were up to something. That’s why she asked us to come out with her this afternoon. And we were expecting your owl call any minute. We couldn’t tell her that, so we simply had to say we’d rather not, and she was very snuffy indeed and said that all the time she’s been here she’d never once heard us recite any poetry, and that as this was her last day we could learn a bit during the afternoon and let her hear it when she came back from leaving cards on people and giving them the good news that she was clearing out.”

“Things looked very black and beastly,” said Peggy.

“She said mother and Uncle Jim used to learn a poem every week, and we knew they did, because they’d told us how awful it was, and then, luckily, she asked Uncle Jim what would be a good bit of poetry for us to learn. And he saved us, and said ‘Casabianca,’ and mother went out of the room in a hurry.”

“But how did that save you?” asked Titty. “It’s a pretty long poem.”

“Because we knew it already, and Uncle Jim knew that we knew it. We had to learn it at school.”

“Theboystoodontheburningdeckwhenceallbuthehadfled,” rattled Peggy.

“So her dark plot was jolly well dished,” said Nancy, “and here we are.”

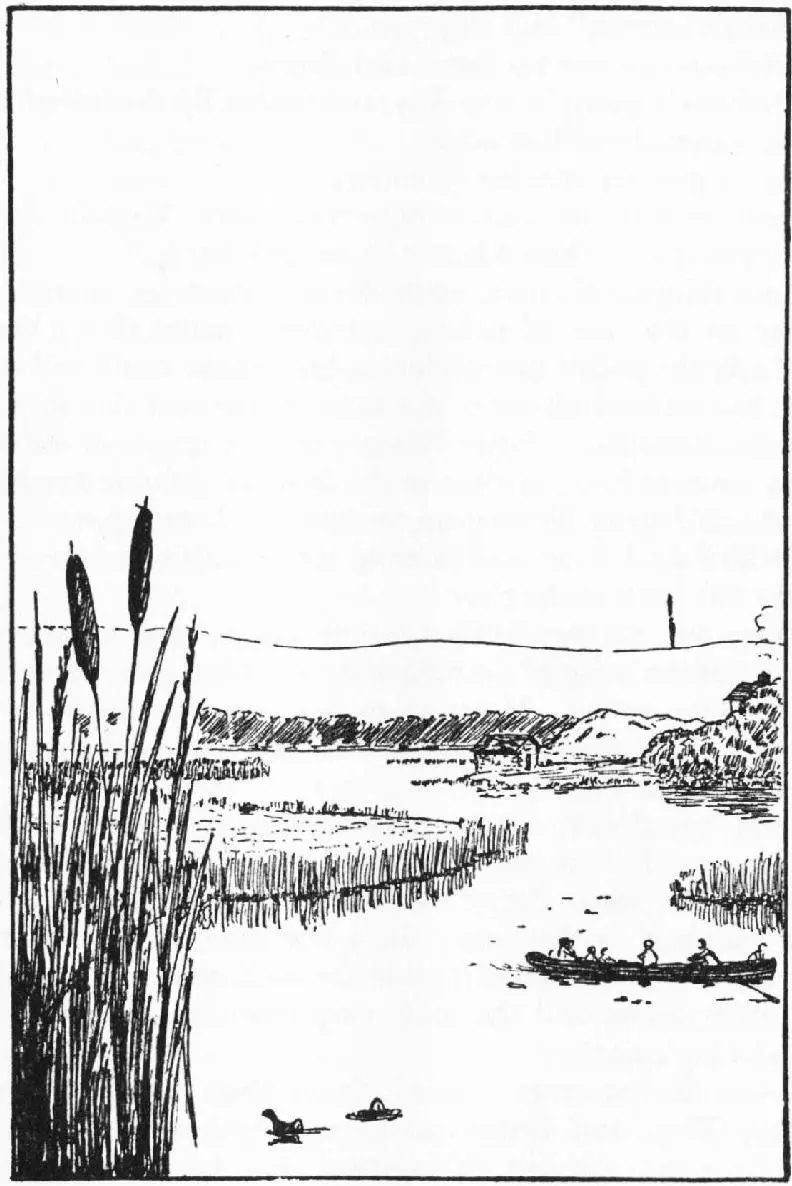

Table of Contents

Above the lagoon the current seemed to be faster, and John began to wish that the war canoe were not so deep in the water. He could see Nancy looking at the reeds at the side of the river, and he knew that she was thinking how slowly they were moving past. But presently Nancy said, “We’re not safe yet, you know. Let’s get the other pair of oars out and make her hum. The G.A.’ll be driving round to the head of the lake and crossing the river at Udal Bridge, and we’d better get above it and out of sight, or mother and Uncle Jim will be dished as well as all of us if the G.A. happens to see us with you while she’s driving round.” After that, with John and Nancy rowing and Peggy telling them which side to pull hardest, they went up the river at such a pace that there might have been no current at all.

“What are we going to do now?” asked Roger, and Peggy was just going to say something, when Nancy stopped her.

“Wait till we get to the first cataract,” she panted. “No talking about plans while we’re rowing. It isn’t fair.”

The war canoe swung upstream, past the great oak tree.

“We wouldn’t have found the boat if I hadn’t crawled in under the branches,” said Roger.

“It’s the best hiding-place on the river,” said Peggy. “Once when we were little and nurse was looking for us, we got into the river underneath it, and crouched there like hippopotamuses with the water up to our necks, and she passed close by the tree and never saw us. But you’ve no idea what a job it was getting the boat there last night, and tying it under the tree in the dark.”

“Did you do it at night?” said Roger.

“Of course,” said Peggy. “Pull right, pull right.”

Above the oak there was a bend in the river and then a straight stretch with little bushes on the banks and no reeds, and at the top of this stretch there was a wide arched stone bridge carrying the road that went round to the head of the lake.

“Are we going through the bridge?” asked Titty.

“In the boat?” asked Roger.

Nancy took a quick look over her shoulder, and then, still rowing hard, spoke to John.

“We can’t quite shoot it against the stream,” she panted. “We go for it full tilt, ship our oars, and scrabble through with our hands. Then as soon as there’s room you get your oars out again and pull for all you’re worth. Peggy’ll sing out when to ship. She knows. We’ve done it again and again by ourselves. It’s easier with someone to sing out. Now then, put your back into it.”

She had been rowing a hard, fast stroke before, but now she rowed faster still. Luckily John had done this sort of thing before, and was able to keep time. There was a good deal of splash, but that hardly mattered. What did matter was speed.

Roger half stood up with excitement, but the next stroke of the two captains sent the boat forward with such a jerk that he sat down hard and there was really no need for Mate Susan to tell him to sit still.

“Right! Right! . . . As you are. . . . Left. . . . A wee bit more. You’re going straight for it. . . .” Peggy shouted her orders. “Two more strokes. . . . Ship your oars!”

As he heard the last word John was already in the shadow of the bridge. There was a rattle and crash as all four oars were lifted from the rowlocks and brought inboard.

“Quick! Quick!” shouted Nancy. “Keep her going.” She was standing in the boat, stooping a little and grabbing at one stone after another under the curved arch of the bridge.

John did the same.

“Heave her along,” shouted Nancy. “Don’t let her slip back. Foot by foot the nose of the rowing boat came out above the bridge. John was through.

“Out with your oars the moment you can,” cried Nancy. “Quick! she’ll swing. Don’t let her. Never mind. (The blade of an oar hit the stonework.) Pull! Good! Oh, good! She’s through now.” Nancy had her oars out in half a second and watched for John’s blades going forward, brought her own after them and with the next stroke was pulling as well as he. “It’s pretty hard work with so much water coming down. That’s all that rain we had the other night.”

“You’ve got a lot of blood on your hand,” said Susan.

“So I have,” said Nancy. “I usually do. Some of these stones are pretty sharp. We’re nearly there, and then I’ll give it a wash. Can’t stop till we’re round that corner.”

Again the river twisted. The bridge was hidden by trees. There was a loud noise of splashing waters. Not very far ahead of them the smooth water ended in foam-covered rocks and a line of low waterfalls that marked the place where the mountain stream changed into the placid little river that wound through the meadows to the lake.

UP THE AMAZON RIVER

UP THE AMAZON RIVER

“First Cataract,” said Peggy.

“Nobody can row up that,” said Roger.

Читать дальше

UP THE AMAZON RIVER

UP THE AMAZON RIVER