But Titty dipped some water for herself and got a little of it into her mouth.

“It’s fresh,” she said to Roger. “It really is the great river of the continent.”

“Is it?” said Roger. “Where’s the boat?”

John and Susan were looking for the war canoe in the rushes on either side of the big tree.

“Perhaps they weren’t able to get out to bring it,” said John.

“I see it,” shouted Roger.

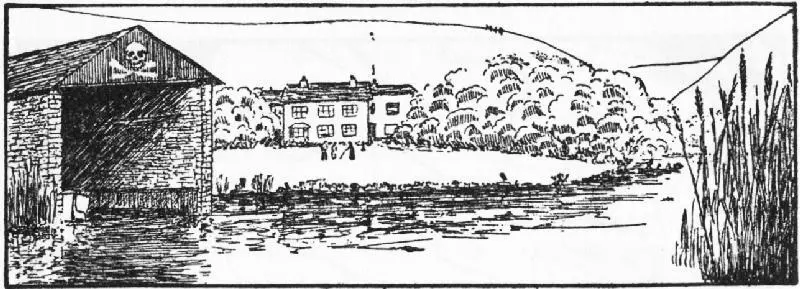

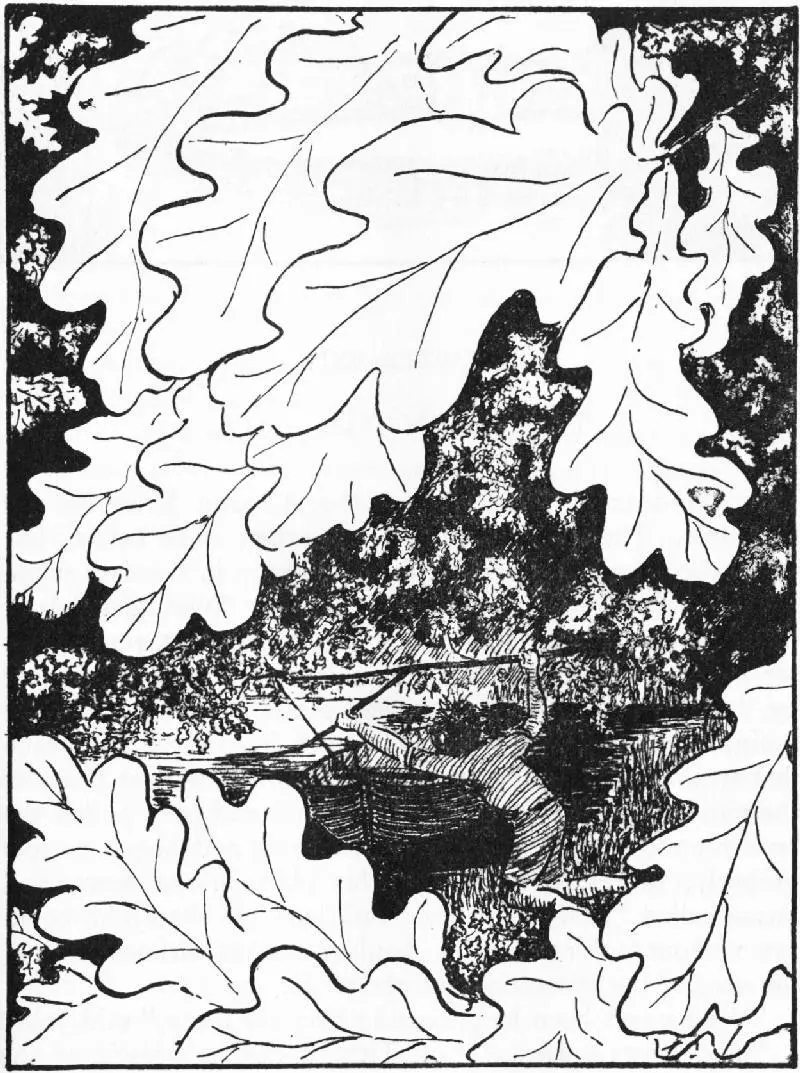

He had crawled right in under the branches of the oak till he could touch its huge trunk. On the other side its branches hung out over the river, the tips of them sweeping the water, and there, under these branches and tied to one of them, hidden so that it could hardly be seen from the river or from the shore except by someone who had crept in under the tree, was a long, narrow, native rowing boat.

“Nobody can beat the Amazons at things like this,” said John.

“But it isn’t a war canoe,” said Roger. “It’s the same as Captain Flint’s boat, or the one at Holly Howe.”

“It’s probably the rowing boat we saw in the boathouse last year,” said John. “Anyhow, it’s beautifully hidden.”

He climbed out on a branch of the oak, untied the painter from it, climbed back, and hauled the boat ashore.

“It’s their boat all right,” he said. “There’s ‘Beckfoot’ painted on the stern. Tumble in. You go to the stern, Mister Mate. We’ll drift down with the current. I’ll take the oars in the bows.”

In another minute the four explorers were crouching in the boat and pulling her out by catching at the oak branches that brushed over them with rustling leaves.

“It’s lucky we don’t wear hats,” said Roger.

Inch by inch they worked her out from under the branches. As soon as they were clear, John put the bow oars out. He pulled a stroke now and then to keep her in the current, and they drifted silently downstream between the swaying walls of pale green reeds.

THE HIDDEN BOAT

THE HIDDEN BOAT

Chapter XXIV.

The Noon-Tide Owl

Table of Contents

The able-seaman was afloat on the Amazon River for the first time. The other three had been there once before, last year, when they had rowed up to the lagoon in the dark while Nancy and Peggy were sailing down to Wild Cat Island where Titty had been left alone in charge. But you cannot see much of a river in the dark and they were glad to see it by daylight. Besides that, it was pleasant to be in a boat again, even if it was not a sailing boat, but only a war canoe that was very much like one of the ordinary rowing boats of the natives. They soon tired of drifting, and John pulled the boat round, shifted to the middle thwart, and began to row properly, while Roger went to his place in the bows, and Susan called “Pull right!” or “Pull left!” so that John could row without looking over his shoulder and yet without running the nose of the war canoe into the reeds.

“We haven’t been long, coming over the moor,” said John.

“The desert uplands,” said Titty, almost to herself, as she sat beside the mate in the stern, looking up to the ridge of moorland along which they had marched from Swallowdale, and seeing all she could of the scraps of meadow that showed through the gaps between the reed-beds.

“We’ve not been long, really,” said John. “But they want us to be as quick as we can.”

“Here’s the lagoon,” said Susan, and the boat shot out into a small lake almost covered by big patches of broad-leaved water-lilies. Even in daylight it was hard not to catch them with the oars.

“We were lucky ever to get out of this place that night,” said John.

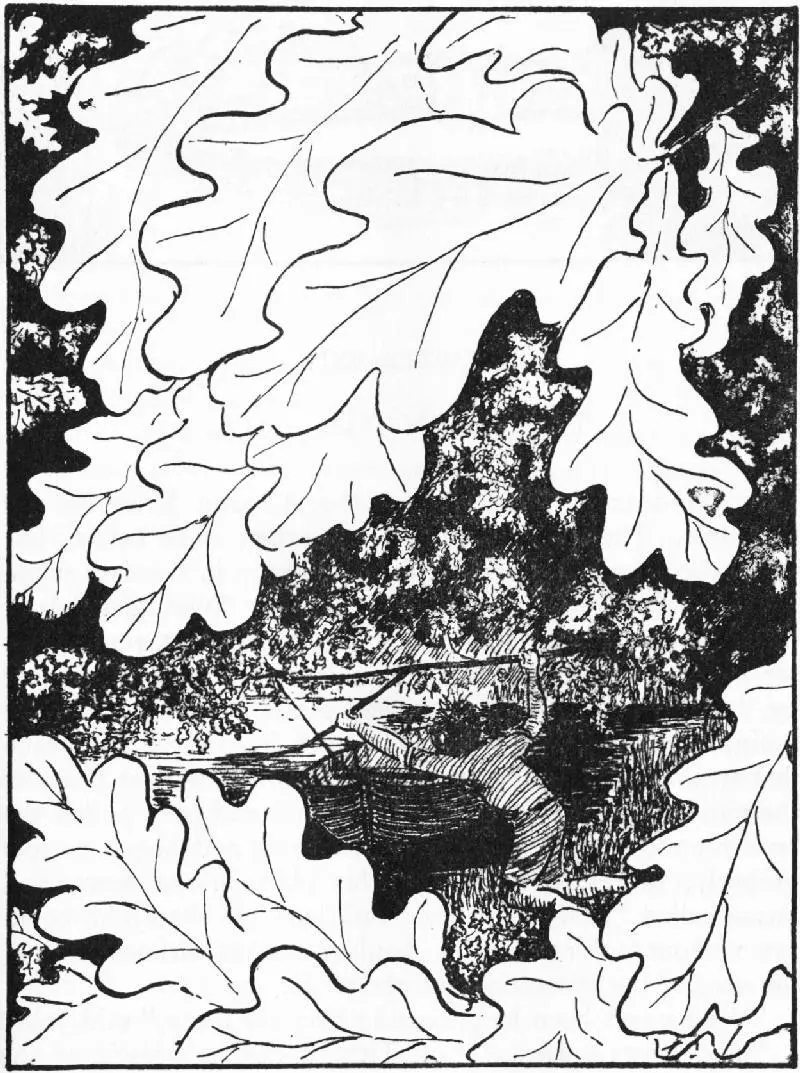

They crossed the lagoon, keeping to the river channel that made a lane between the patches of water-lilies. Then the reed-beds on either side closed in on them again and once more they were in the narrow river. On the right bank, trees came down to the water’s edge.

“Steady,” said the mate. “We shall be in sight of the house in half a minute. I can see its roof already. This must be the wood they meant.”

John glanced over his shoulder, shipped his right oar, and backwatered gently with his left. The war canoe swung round and slid with a low swishing noise into the reeds, on and on, until even Susan and Titty, sitting in the stern, had reeds all round them. It lost way. John stood up and used an oar as a pole. Another yard through the reeds, another foot, and “Can you jump it, Roger?”

There was a jerk astern as the ship’s boy jumped. Then with another jerk the painter drew taut, and he hauled the boat’s nose up against the soft shelving bank.

For the last time Captain John read carefully through the message from the Amazons. Then he gave it to the mate.

“I might be captured,” he said, “and it would be a pity to have to swallow it.”

He stepped ashore.

“Be ready to cast off in a moment,” he said. “And if you’re attacked pull across to the other side of the river. Don’t leave the boat. Stay in it or close to it. You’ll hear the owl calls, I should think. But whatever other noises there are, don’t come. That’s right, Roger, don’t make the painter fast. Be ready to slip and bolt for it.”

He was gone.

Mate Susan laid the oars ready, but inside the boat, so that if she had to shove off in a hurry they would not catch in the reeds. She went ashore to see if the ship’s boy was in a dry place or getting his feet wet, for the reeds were so thick that she could see nothing from the boat. She listened for the noise of breaking twigs or the rustle of last year’s leaves that would show where the captain was. But there was not a sound. The trees in the wood were close together and very thick. It would be possible for natives to creep through them until they were so near the bank that they could dash out and seize the boat. The mate thought it better to have everybody aboard. Roger found that the painter was just long enough to go round a tussock of grass and back into the bows of the boat, so that he could sit in the boat and hold the end of it and be ready to let go in a second. A ration of chocolate was served out.

“He’s been gone ten minutes at least,” said the mate.

“Nearly an hour,” said Roger.

Then came the owl call. “Tu whoooooooooooo. Tu whoooooooooooo.” It sounded a long way from the river.

“He’s done it beautifully,” said the mate. “I’ve never heard him do it so well.”

“Anybody might think it was a real one,” said Titty.

“Some real ones aren’t half so good,” said Roger.

There was silence for about a minute. Then again they heard the owl call, far away, but not, they thought, in quite the same place. Then silence for a very long time.

“Perhaps he’s fallen into an ambush,” said Titty. “Hadn’t we better go and help?”

“He said we were to stick to the boat. He may have had to go a long way round to get back.”

They sat still, listening, hardly breathing. For a long time there was no noise at all. Then they heard a branch creak and steps on the bank, and a moment later the reeds parted and there was John.

“Hullo!” he said. “Aren’t they here?”

“No,” said Roger.

“They’re coming. At least I think they are.”

“Did you see them?” asked Susan.

“Were they behind bars?” asked Titty, “or had they already got out? Were they in disguise? And, oh, John, did you see anybody else?”

Читать дальше

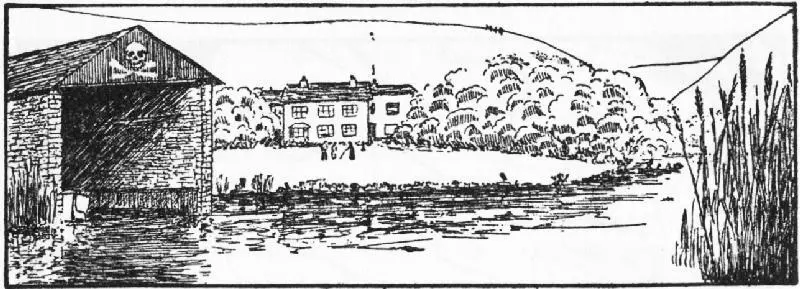

THE HIDDEN BOAT

THE HIDDEN BOAT