Contemporary studies have reported en‐bloc resection of the pelvic sidewall for both locally advance and recurrent rectal cancer involving the lateral pelvic neurovasculature with good outcomes [63]. Similarly, extended lateral wall resection is possible in advanced gynecological tumors [64]. Some units are providing “higher and wider” resections for tumors involving the common and external iliac vessels [65, 66] and extending to the sciatic nerve and ischial bone [2, 57, 67]. Reported R0 resection rates range from 38 to 58%, with no perioperative mortality, and 96–100% long‐term graft patency [65, 66].

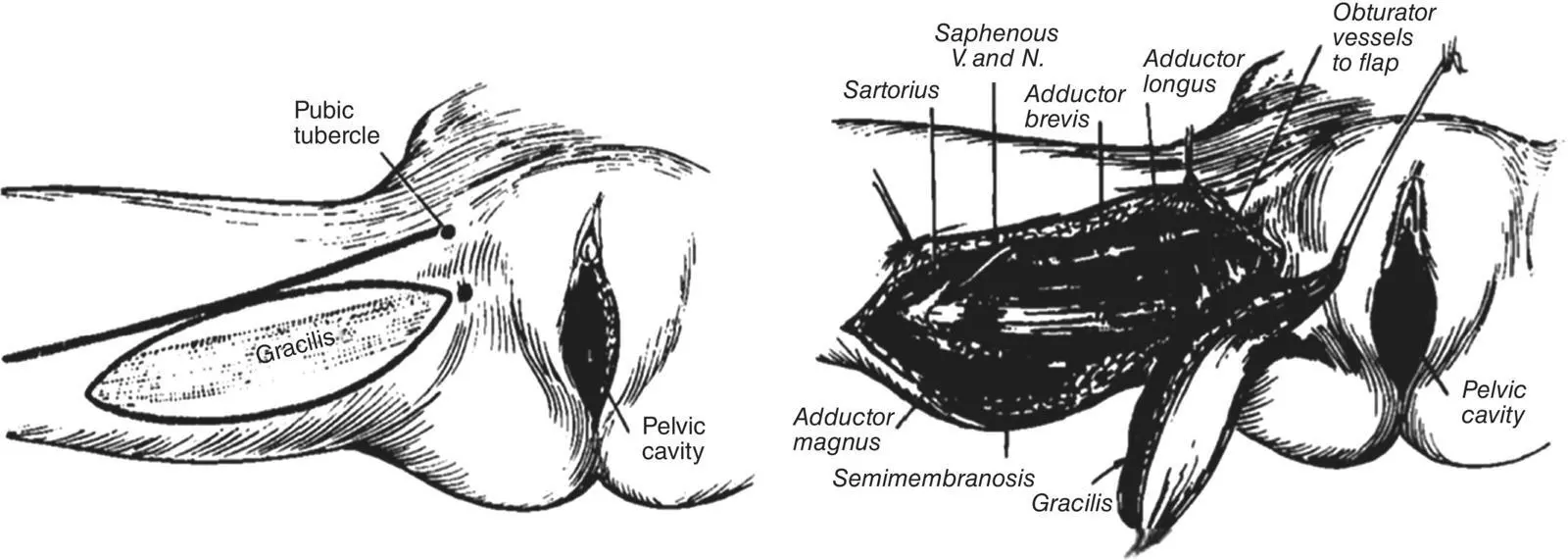

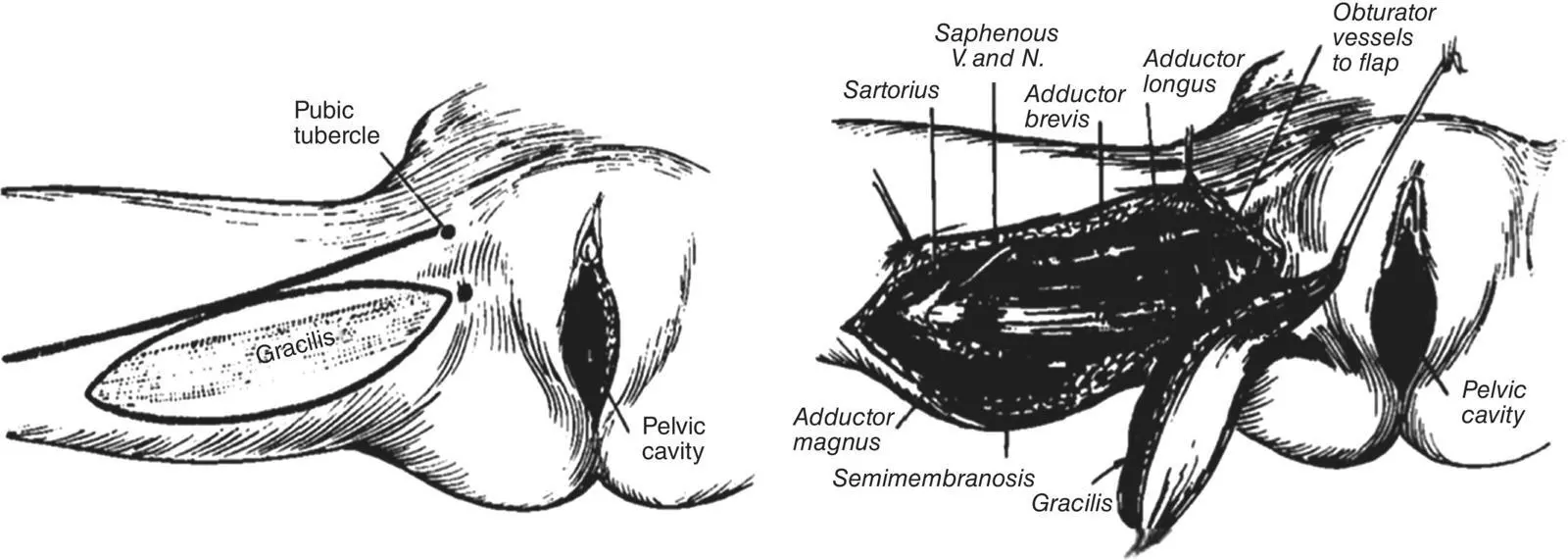

In the original series, after the exenteration was performed, the pelvis was generally packed and allowed to heal by secondary intention. Later, surgeons closed the perineum in two layers, to prevent the small intestine prolapsing into the pelvic cavity [1]. In recent decades, various techniques for filling the “dead‐space” have been examined. The omental pedicle flap was reported as an adjunct in keeping the small bowel and urinary conduit from prolapsing into the pelvic cavity, with the hope of reducing fistula rates [68, 69]. In addition, the use of mesh reconstruction of the pelvic inlet, colonic advancement, and locoregional myocutaneous flaps have been advocated with varying degrees of success ( Figure 1.5) [70–72]. The use of flaps in particular was an important development that simultaneously allowed closure of perineal wounds not amenable to primary closure and transfer of viable tissue into the pelvis to decrease septic and perineal complications [73, 74]. Moreover, myocutaneous flaps may be used to construct a neovagina [75, 76].

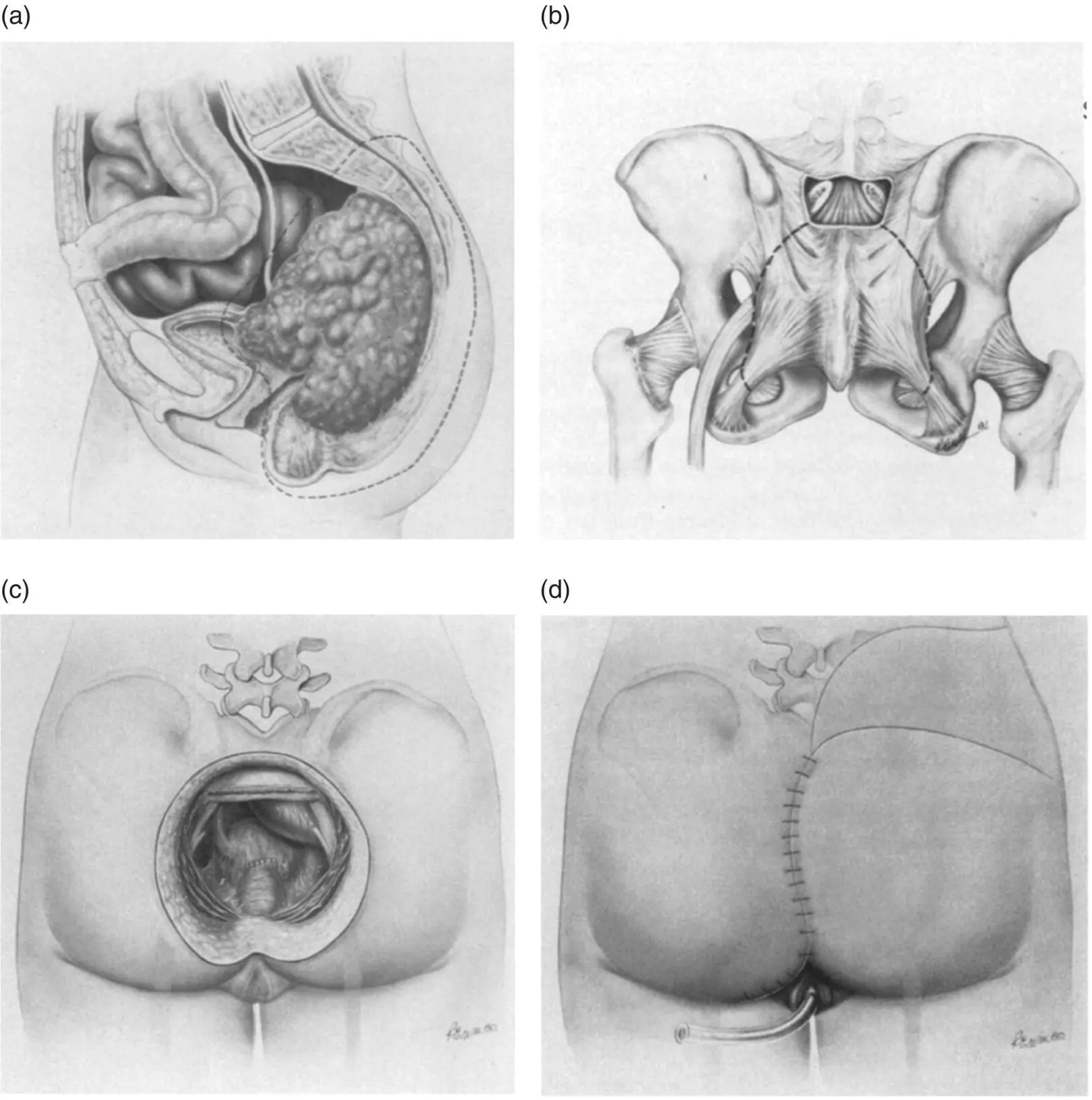

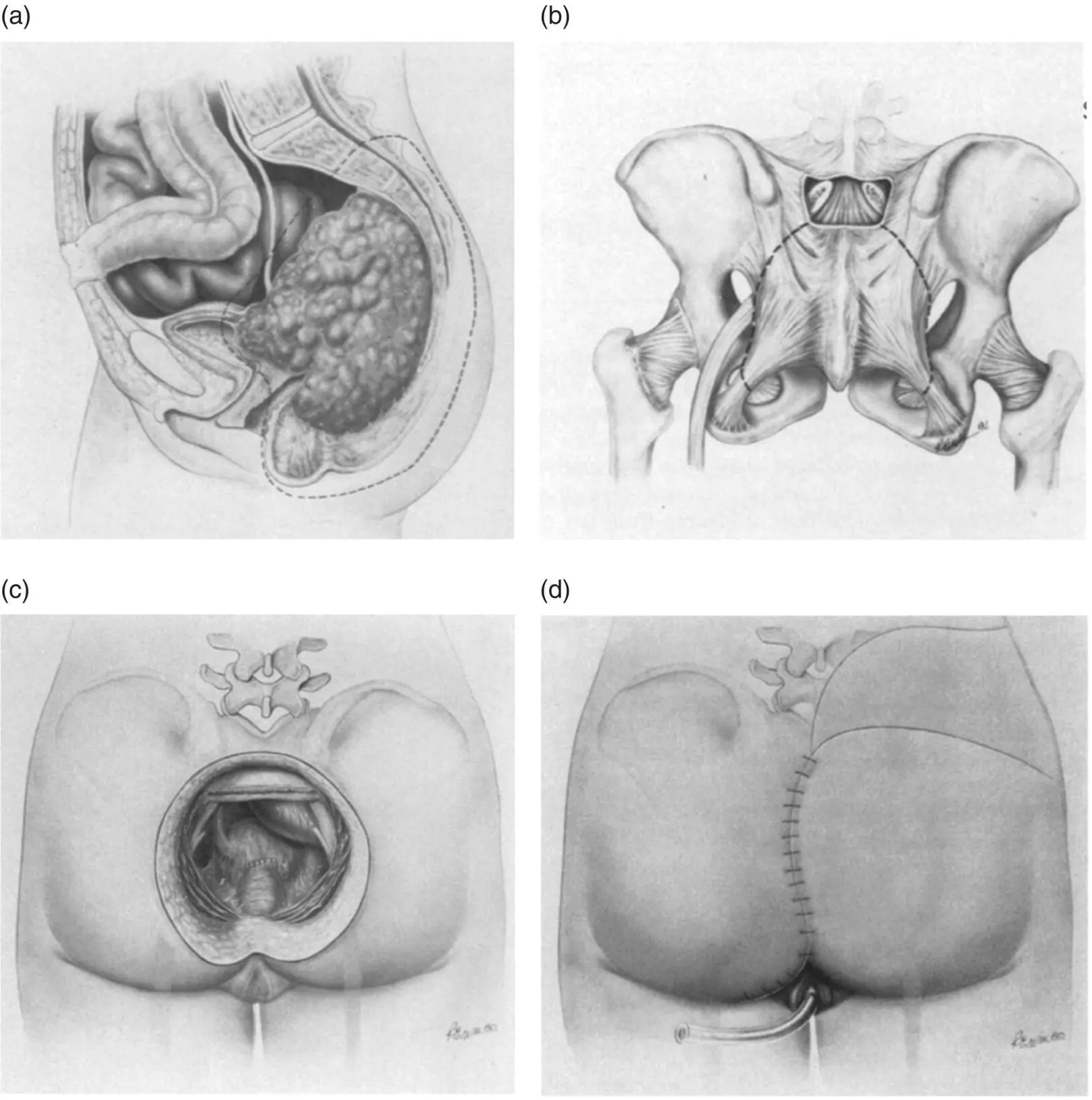

Figure 1.4 Diagrams from the first description by Wanebo and Marcove of abdomino‐prone sacral resection showing the extent of resection required for recurrence of rectal cancer in the posterior compartment (A), lines of transection of the sacrum from the posterior approach (B), the operative defect after sacral resection (C), and rotational skin flaps for wound closure (D). Copyright © 1981 J.B. Lippincott Company.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Wolters Kluwer [49].

The ability to perform radical and extended pelvic cancer surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for patients with locally advanced or recurrent pelvic tumors.

Better diagnostics and chemotherapeutics are likely to be “key” in personalizing patient care, improving survival, or converting unresectable disease to resectable. In addition, there is growing research on quality‐of‐life outcome data following extended radical surgery. This is increasingly becoming as important an outcome measure as survival. The PelvEx Collaborative, offers an unique opportunity to prospectively assess exenterative outcomes, refine treatment options and further improve the management of advanced pelvic malignacies.

Figure 1.5 Gracilis myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of the perineum after PE as described by McCraw et al. in 1976. Copyright © 1976 Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Wolters Kluwer [70].

1 1 Brunschwig, A. (1948). Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma; a one‐stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer 1 (2): 177–183.

2 2 Brown, K.G.M., Solomon, M.J., and Koh, C.E. (2017). Pelvic exenteration surgery: the evolution of radical surgical techniques for advanced and recurrent pelvic malignancy. Dis. Colon Rectum 60 (7): 745–754.

3 3 Harji, D.P., Griffiths, B., McArthur, D.R., and Sagar, P.M. (2013). Surgery for recurrent rectal cancer: higher and wider? Colorectal Dis. 15 (2): 139–145.

4 4 PelvEx Collaborative (2019). Surgical and survival outcomes following pelvic exenteration for locally advanced primary rectal cancer: results from an international collaboration. Ann. Surg. 269 (2): 315–321.

5 5 PelvEx Collaborative (2018). Factors affecting outcomes following pelvic exenteration for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 105 (6): 650–657.

6 6 Bricker, E. (1994). Evolution of radical pelvic surgery. Surg. Clin. North Am. 3: 197–203.

7 7 Appleby, L.H. (1950). Proctocystectomy. Am. J. Surg. 79 (1): 57–60.

8 8 Brintnall, E. and Flocks, R. (1950). En masse pelvic viscerectomy with uretero‐intestinal anastomosis. AMA Arch. Surg. 61 (5): 851–868.

9 9 Morris, J.M. and Meigs, J.V. (1950). Carcinoma of the cervix; statistical evaluation of 1,938 cases and results of treatment. Surg. Gynecol. Obstetr. 90 (2): 135–150.

10 10 Parsons, L. and Bell, J.W. (1950). An evaluation of the pelvic exenteration operation. Cancer 3 (2): 205–213.

11 11 Kenny, M. (1947). Relief of pain in intractable cancer of the pelvis. Br. Med. J. 2 (4534): 862.

12 12 Weinberg, A. and Kaiser, J.B. (1950). Pelvic evisceration for advanced persistent or recurrent carcinoma of the cervix. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. Br. Empire 57 (4): 605–607.

13 13 Whipple, A.O., Parsons, W.B., and Mullins, C.R. (1935). Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Ann. Surg. 102 (4): 763–779.

14 14 Boronow, R.C. (2008). Remembering Alexander Brunschwig, MD (1901–1969). Gynecol. Oncol. 111 (2): S2–S8.

15 15 Parsons, L. and Leadbetter, W.F. (1950). Urologic aspects of radical pelvic surgery. New Engl. J. Med. 242 (20): 774–779.

16 16 Brunschwig, A. and Daniel, W. (1954). Total and anterior pelvic exenteration. I. Report of results based upon 315 operations. Surg. Gynecol. Obstetr. 99 (3): 324–330.

17 17 Brunschwig, A. (1954). What can surgery accomplish in recurrent carcinoma of the cervix? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 68 (3): 776–780.

18 18 Brunschwig, A. and Daniel, W. (1956). Pelvic exenterations for advanced carcinoma of the vulva. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 72 (3): 489–496.

19 19 Barber, H. and Brunschwig, A. (1965). Pelvic exenteration for locally advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer. Review of 22 cases. Surgery 58 (6): 935.

20 20 McCullough, D.L. and Leadbetter, W.F. (1972). Radical pelvic surgery for locally extensive carcinoma of the prostate. J. Urol. 108 (6): 939–943.

21 21 Marshall, V.F. (1956). Pelvic exenteration for polypoid myosarcoma (sarcoma botryoides) of the urinary bladder of an infant. Cancer 9 (3): 620–621.

22 22 Brunschwig, A. (1951). Partial or complete pelvic exenteration for extensive irradiation necrosis of pelvic viscera in the female. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 93 (4): 431–438.

23 23 Beer, E. (1929). Total cystectomy and partial prostatectomy for infiltrating carcinoma of the neck of the bladder: report of eight operated cases. Ann. Surg. 90 (5): 864–885.

24 24 Lopez, M.J., Petros, J.G., and Augustinos, P. (1999). Development and evolution of pelvic exenteration: historical notes. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 17 (3): 47–151.

25 25 Hinman, F. and Belt, A.E. (1922). An experimental study of ureteroduodenostomy. JAMA 79 (23): 1917–1924.

26 26 Coffey, R. (1911). Physiologic implantation of the severed ureter or common bile‐duct into the intestine. JAMA 56 (6): 397–403.

27 27 Coffey, R. (1925). A technique for simultaneous implantation of the right and left ureters into the pelvic colon which does not obstruct the ureters or disturb kidney function. Northwest Med. 24: 211–214.

Читать дальше