Exploring Culture: Could the Average Roman Read?

“Stronius knows nothing!” “Vote for Popidius Ampliatus and Vedius Nummianus!” “Rufus loves Cornelia.” The walls of Pompeii are covered with graffiti written by residents and visitors to the town, but how many people could read them?

Some scholars have suggested that the percentage of inhabitants of the Roman empire who were literate was as low as 10%. If we are interested in those who had formal training and could read and especially write Roman history or poetry, that number might not be far off. Our written texts clearly come from this segment of the population.

There is reason to believe that literacy was more widespread from an early period in Roman history. Rome possessed a written law code from the middle of the fifth century BCE and it seems to have been a point of importance to the lower classes to have important public documents made available publicly in writing. It is possible that relatively limited numbers of the lower classes could read these documents for themselves, but clearly some outside of the elite circles possessed this ability and could either share it with others or read when need be. At the same time, the language of the early law codes suggests that many agreements were verbal and that witnesses might be crucial to establishing them. Written contracts for transactions were not the norm.

The graffiti from Pompeii falls further out on the literacy spectrum. For one thing, this evidence dates to 79 CE, two hundred or more years after Rome had established itself as the dominant city in the Mediterranean, and it is likely that literacy rates had improved as more money flowed into Rome from her conquests. However, it also suggests a more widespread picture of literacy: it would make little sense to go to the trouble and expense of expressing oneself on the walls of the city if only a small percentage of the city’s population could read them. Some of the graffiti even engage in conversation with other messages, indicating that the author of the second graffiti, or perhaps a friend, had read the first post. The graffiti at Pompeii might be seen as the social media of its day, which certainly implies a higher level of literacy than 10% if one is willing to count composing tweets on subjects ranging from politics to sports to sex.

Further down the literacy spectrum, it seems likely that the majority of Romans could at least recognize the letters of the alphabet. Individual letters have been found on building blocks and roof tiles, suggesting that manual laborers could recognize these for use in construction projects. The letters SPQR (the abbreviation, still used, for “the Senate and People of Rome”) appear frequently, apparently familiar enough that recognizing these four letters would be enough to indicate the involvement of the Roman state.

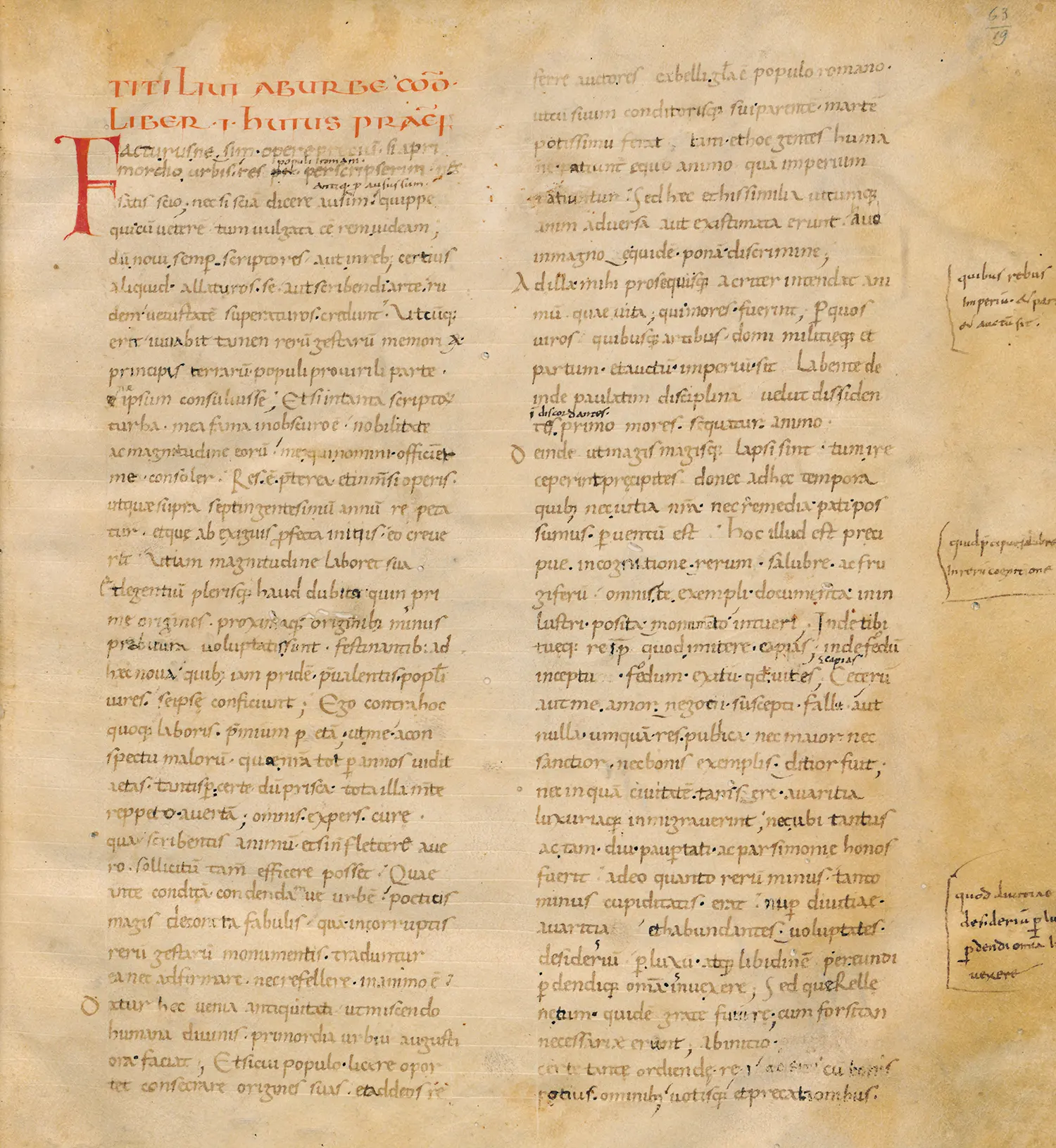

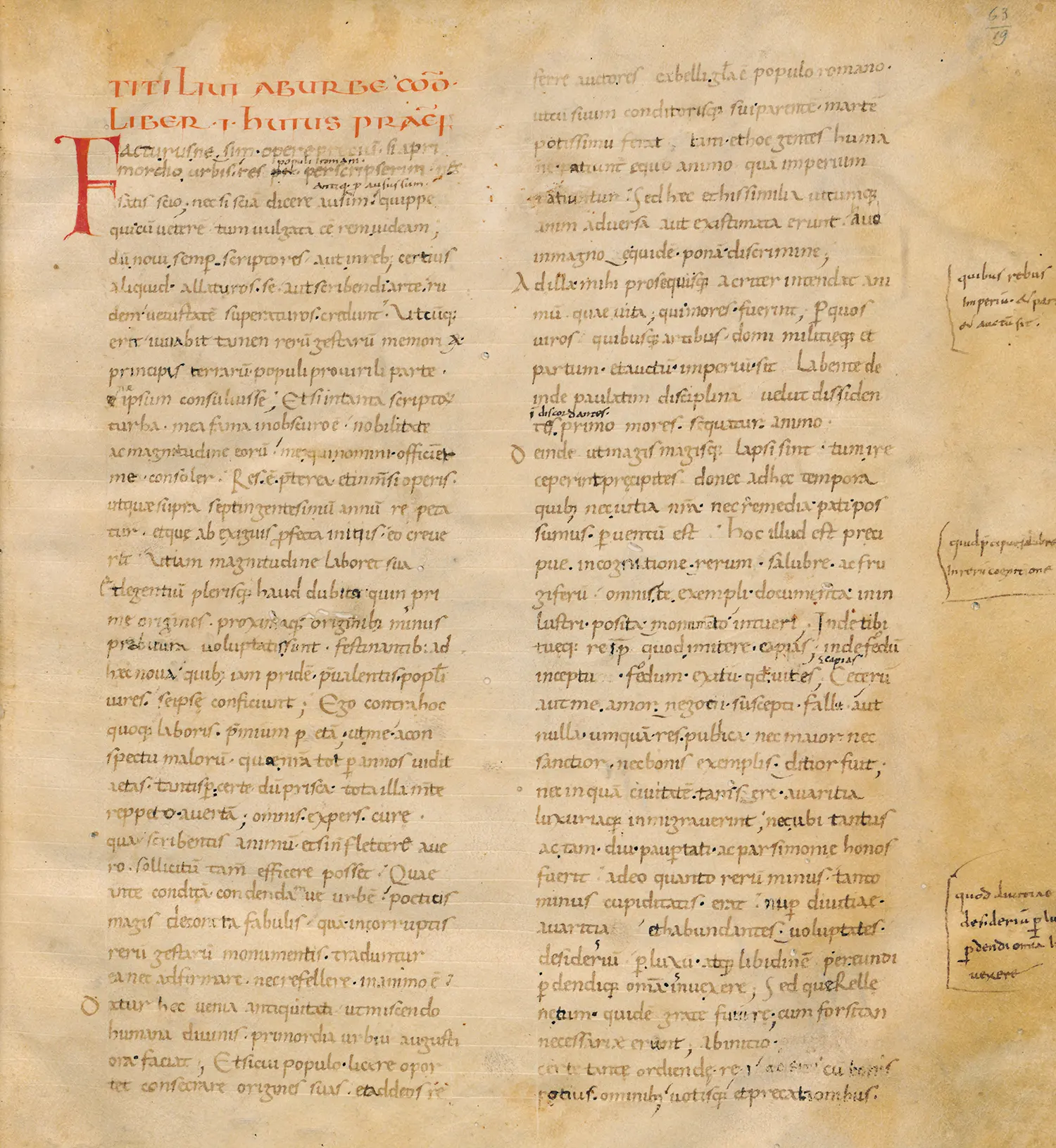

Like other non-literate societies, most communication in Rome, including stories about the past, was handed on orally from one person to another. Adding to the challenge, whatever written texts might have existed prior to 390 BCE were probably destroyed when the Gauls sacked Rome in that year. This situation means that Roman historians face particular challenges: we lack contemporary texts for the first 600 years of Rome’s history and we have only scattered contemporary texts for the next hundred. The vast majority of surviving Latin texts date from after 80 BCE, and our copies of them come from many centuries after that (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Fol. 1r from ms Plutei 63.19, a tenth century CE manuscript of Livy, originally copied in Verona and now in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana in Florence.

On the one hand, the absence of texts from the earliest years of Rome’s history might appear to be a serious problem: the distance between Livy and the death of Romulus is greater than that from us to Christopher Columbus, but as we have discussed, later texts do not mean that they have no valuable information about early Rome. It means that we have to ask different questions about someone like Livy, who drew on earlier written material that we no longer have, than we would about other authors. Knowing when authors were writing is important because we can use that knowledge to ask questions more appropriate to that historian and therefore more useful to us in attempting to understand Roman society.

The abundance of sources dating after 80 BCE means that a Roman historian does have plentiful eyewitnesses for the Late Republic (133–31 BCE; see Chapter 2for an outline history of the Roman Republic). Chief among these are the texts of the Roman orator and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero(106–43 BCE). Cicero provides us with three different types of texts: speeches written and delivered primarily in the law courts, philosophical treatises, and personal letters to family and friends. Because Cicero apparently did notintend for his letters to be made public, they are often the most revealing source. His correspondents ranged from leading politicians of his day to his wife and daughter and his best friend Atticus, and the letters range over a wide set of topics, from politics to personal matters such as the death of his daughter in childbirth. Not only do they allow us to see his unpolished opinions about affairs of state or others in the Roman elite, but we get glimpses into his actual day-to-day activities and his family life. No other source can compare to Cicero, which sometimes has the consequence of giving too much weight to the evidence we get from him.

Indeed, Cicero’s writings suffer from a flaw common to almost all literary sources from antiquity: they give us a slice of life for the upper class only. The texts we have usually emerged from elite society, the top 1% of the Roman world, and we have no historical texts authored by a woman, restricting us to one-half of that 1%. Compounding the problem, the elite tended not to be interested in the lives and concerns of the non-elite and so rarely wrote about them. Cicero’s correspondents are almost entirely other members of the elite; in the surviving collection are only four letters to his wife and four letters to his secretary Tiro. One challenge we will have to take up in this book is how to make the silence speak: how to learn something about the lives of women and the other 99% of Rome’s inhabitants despite the nature of our sources.

One way that modern historians try to fill the gaps in our picture is through comparative history. While recognizing that every society is unique in its details, anthropologists and other specialists have often been able to identify features that can be found in multiple societies. For instance Rome, as we will see, was a heavily agrarian society, dependent on farming for the majority of its economic output. As such, it likely shared certain features with other agrarian societies, such as the seasonal nature of the cycle of work: manufacturing societies are less dependent on the sun and rain for survival. Similarly, almost all pre-modern societies, because they lacked modern medical knowledge and equipment, suffered from very high infant mortality rates and shorter life spans than today. By looking to other societies and considering the ways in which they might compare to Rome, a Roman historian can get a better overall picture of Roman society, even if that picture remains fuzzy around the edges.

Another tool that Roman historians use to get around the problem of sources is to consider a much wider collection of texts than are normally considered “historical”. To some extent, all literary creations might be considered historical. Even if they were not written for the purpose of recounting historical events, they reveal critical elements of their society. Think of movies in our own society: the story may be fictional, but the movie shows us how people dressed at the time, what cars they drove, and how they lived. Sometimes a movie can tell us something of the values of the people at the time: how men and women related to each other or to their jobs. Theater played this role for the Romans. Among the earliest written Latin texts are comedies by Plautus(c. 250–184 BCE) and Terence(c. 190–160 BCE), both of whom came from outside the elite class. The depiction of women and enslaved persons upon the stage provides some useful material, even if the representations may be exaggerated or distorted for comic effect. In a later period, the love poetry of poets such as Catullus(87–54 BCE), Propertius(c. 50–16 BCE), and Ovid(43 BCE–17 CE) can suggest something of how Roman men conceived of relationships and how they expected women to behave. These texts, which drew on Greek predecessors, are also an essential resource for understanding how the Romans responded to Greek culture, which in turn helps us understand how the Romans thought about their own place in the world. For that reason, we will return repeatedly to the Roman response to Greek culture in learning about the Roman Republic.

Читать дальше