How the November pogroms were received by the German people and to what extent they approved of them is still a subject of controversy. Can the indifference that according to sources characterized the great majority of the population already be seen as an indication of ‘passive complicity’ (Kulka/Rodrigue), or does the awkward silence point instead to an ‘embarrassed distance’ (Frank Bajohr)? 34In endeavouring to arrive at a balanced judgement it should not be forgotten – as Peter Longerich recently emphasized again – that in the Third Reich there was no such thing as public opinion built on the free expression of personal views. Under National Socialism, ‘public opinion’ always meant ‘the public opinion staged, controlled and manipulated by the regime’. In this area, ‘in which the guiding principles and interpretive models were reproduced’, it was very dangerous to confide one’s views to another person unless one was sure that this other person shared them. 35

As a result, there are few documents that provide reliable answers to the question as to what most Germans thought in November 1938. The government-commissioned reports on the situation and public opinion, including reports made by local offices regarding the success of the measures taken, are sources that have to be evaluated critically, as are the ‘Deutschland-Berichte der SOPADE’ produced by the leadership of the Social Democratic Party in exile in Prague. Although the idealists in exile tended, for understandable reasons, to greatly overestimate Germans’ covert resistance to Hitler, we nonetheless have to agree with their general conclusion that ‘the riots were strongly condemned by the great majority of the German people.’ 36But this condemnation was nowhere expressed in open protests.

The collection of materials published last year by the Wiener Library made a significant contribution to our understanding of the initial impression from the point of view of the victims. 37Immediately after the outbreak of the pogroms, the Jewish Central Information Office in Amsterdam had begun to collect all the information it could get its hands on in order to find out exactly what had happened and which Jewish communities were affected in what way by the catastrophe. The exchange of personal communications, names and dates was intended to help put an end to uncertainty concerning the survival of relatives and friends.

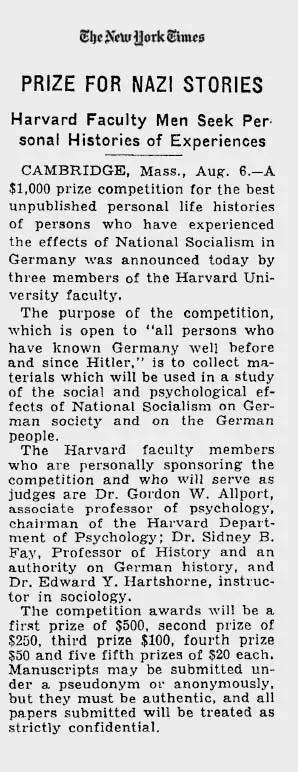

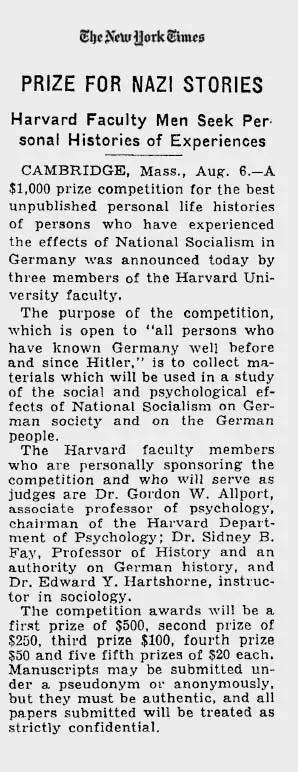

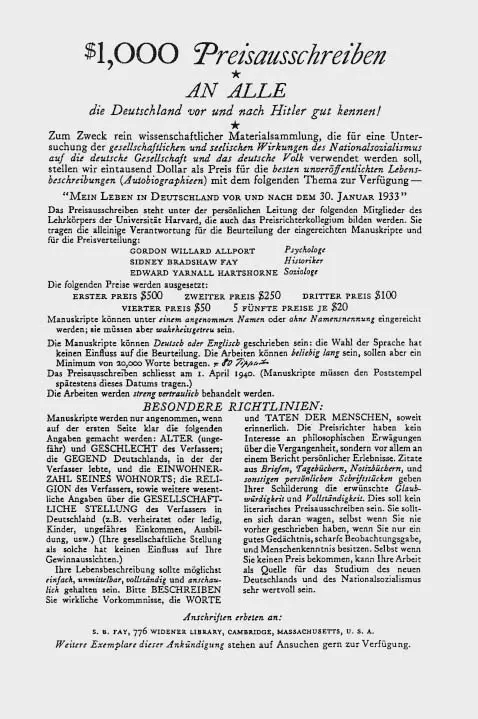

At its outset, the present book also reaches back seventy years, but has an entirely different background. On 7 August 1939, nine months after the pogroms, the New York Times reported, under the headline ‘Prize for Nazi Stories’, that scholars at Harvard University were seeking eyewitness accounts of life in Germany before and after 1933 and to this end had organized a competition with prizes totalling one thousand dollars. Anyone who could report, on the basis of his own experiences, on how everyday life had changed after Hitler’s seizure of power, was eligible to enter the contest. These reports could be presented anonymously or under a pseudonym, and were to be handled with strict confidentiality – ‘but they must be authentic’.

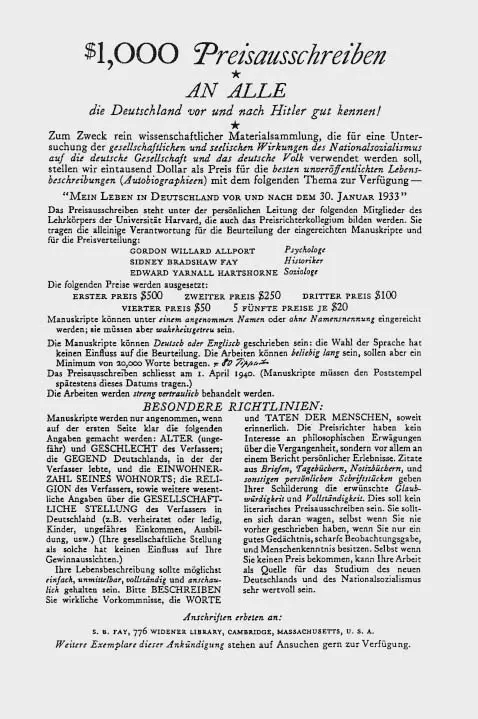

‘My Life in Germany Before and After 30 January 1933’ – that was the name given the prize competition, and the detailed invitation, written in German, to submit entries which was subsequently distributed all over the world by Jewish information offices and aid associations outlined the project very exactly. The life stories should be about eighty pages long, ‘ as simple as possible, direct, complete, and vividly recounted ’. Only ‘real occurrences’ should be described, and therefore anyone who had ‘a good memory, a gift for sharp observation and a knowledge of people’ could take part, even if he had never written anything before. ‘Quotations from letters, notebooks , and other personal writings give your description the desired credibility and completeness .’ Those who did not win a prize could also be sure that their ‘work could be very useful for the study of the new Germany and National Socialism’. The deadline for submissions was 1 April 1940.

Figure 1:Prize advertisement

More than 250 manuscripts from all over the world were received in Cambridge. Of these, 155 came from the United States, 96 of them from New York alone; 31 authors gave return addresses in Great Britain, and 20 sent their contributions from Palestine. Six manuscripts were mailed in from Shanghai, the only territory in the world where no visa was required and where a Jewish enclave had therefore rapidly grown up. Moreover, not only Jews who had emigrated from Germany responded to the call. For example, a Silesian confectioner who had been hired as a cook by the merchant navy and who was now confined in a British camp as an ‘enemy alien’ expressed his enthusiasm for the new Germany, as did an au-pair girl from Berlin who happened to be in America when war broke out – but these texts were exceptions. The great majority of those who submitted reports were Jews who had left Germany and Austria after the pogroms of November 1938.

Most of them had lived in large cities; 61 came from Berlin and 39 from Vienna. The liberal professions, lawyers and doctors, university lecturers and members of the writing community were overrepresented; however, in addition to representatives of the wealthy bourgeoisie, salesmen and people who had eked out a living with occasional jobs also wrote contributions. About a quarter of the accounts came from women.

The participants’ motives varied as much as the social milieus from which they came. With the first-place prize of 500 dollars, an emigrant could survive for several months in most countries, and more than one participant described winning a prize as his ‘last hope’. Others had literary ambitions; even though it was expressly mentioned that this was not a literary contest and that the judges had ‘no interest in philosophical considerations’, a few complete novel manuscripts were submitted. The organizers helped some of these authors by putting them in contact with publishers and editors; some participants, disappointed that their contributions neither received a prize nor were published, demanded that their work be returned to them. In individual cases, the researchers at Harvard also tried to do something for those who had been interned by the British and transferred to camps in Australia or Canada.

The chief motive of most of the participants was, as the Berlin publicist Wolf Citron put it, ‘to say farewell to Germany by working through and recapitulating what was experienced’. No one did so as radically as Moritz Berger, 21, who gave his account the title ‘Revenge’ and ‘dreamed of being a bomber pilot and reducing his home city to ruins’. 38However, all the accounts agreed that the unrestrained brutality of National Socialism on the night of 9 November 1938 represented the greatest breach of civilization in western history, and that it was, for a German Jew, simply unthinkable ever to live in that country again. ‘Nie mehr zurück in dieses Land’ (‘Never back to that country’), wrote the Berlin doctor Hertha Nathorff one week after the pogrom, ‘once we have left it alive.’ Several authors concluded their memoirs by adopting the prize competition’s title, summarizing the irreversibility of the events in the sentence: ‘So endete mein Leben in Deutschland’ (‘So ended my life in Germany’).

Читать дальше