Heydrich did not have much time to transform his orders into specific actions. His telegraph to all police chiefs, which went out around 1.20 a.m. – ‘Flash, urgent, pass on immediately!’ – was completely unambiguous. The police forces received orders not to hinder the ‘demonstrations’ likely to occur throughout the Reich, and to intervene only if German property was endangered. ‘Businesses and apartments belonging to Jews are only to be destroyed, not plundered.’ The police actions were to be led by the local state police departments or by security police inspectors, who were also expected to see to it that ‘as soon as the events of this night allow the use of the regular officials’, as many Jews as ‘could be accommodated in the available holding cells’ were immediately arrested. At first, only male Jews who were healthy, not too old, and if possible, wealthy, were to be arrested and transported to the concentration camps concerned after consultation with camp officials. 25Barely 64 hours had passed since the shooting in Paris.

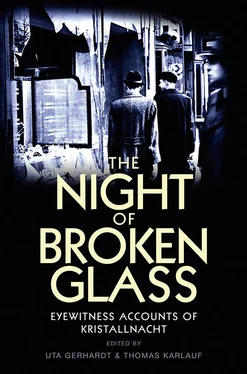

On the morning of 10 November, synagogues all over Germany were put to the torch. The fire brigade was allowed to intervene only if the fires threatened to spread to neighbouring buildings. Thousands of apartments were demolished during that night, and thousands of Jewish businesses were smashed to bits in the course of the following day. The broken glass that piled up in the streets gave the night the ironically euphemistic name of Kristallnacht , ‘the night of broken glass’. It is estimated that 400 people were murdered or driven to suicide. About 40,000 Jews were arrested, and 30,000 of them were sent to Dachau, Buchenwald or Sachsenhausen, 26where they were subjected to the cruellest harassment. Those who were lucky enough to be able to prove that they had the necessary visas and were about to emigrate were released; the number of Jews who died in concentration camps as a result of the ‘November action’ is estimated to be about 1,000. Whereas in the first half of 1938 only about 14,000 Jews had emigrated from Germany, the number of emigrants now rose dramatically. By the end of 1939, about 100,000 Jews had left Germany, and another 100,000 had left Austria. Most of those who remained were poor or old.

During lunch in the Osteria in the Schwabing area of Munich, Goebbels gave the Führer a report. ‘He approves of everything. His views are very radical and aggressive.’ 27Others were less enthusiastic; Göring, who had travelled back from Berlin the previous night and had not been informed, telephoned Hitler to complain about the enormous economic damage that had been incurred. While Goebbels was busy winding down the actions before ‘mob rule took over’ 28and instructing the press to play down the events – ‘no big headlines on page one, no pictures for the time being’ 29– Göring was preparing for the Saturday morning meeting, at which the next steps to be taken against the Jews were to be coordinated with account taken of economic considerations. The declared goal of the 12 November meeting, which lasted several hours and in which representatives of all the departments concerned participated – over a hundred persons from the interior, finance, economic affairs and justice ministries, from the Foreign Office, the Reichsbank, and so on – was the complete exclusion of Jews from German economic life. The idea of the new measures was to isolate them and put them under pressure so they would be forced to leave Germany rapidly and in large numbers. Heydrich had had Eichmann specially brought in from Vienna in order to report on his experiences there.

The decisions made on 12 November can once again be traced in essence back to Hitler himself. In 1936, in his memo on the Four-Year Plan, he had already demanded that ‘the whole of Jewry be held responsible for all the damage individual examples of this criminality have done to the German economy and thus to the German people’. 30As retribution for Gustloff’s murder, he suggested that Jews be subjected to collective punishment, but at the time this plan was not realized because of bureaucratic reservations expressed by the ministries, and especially because of Göring’s concerns. Now Göring took up the idea and on 12 November issued an order to the effect that the Jews, as ‘atonement’ for their hostile attitude toward the German people, should pay a fine of one billion Reichsmarks. The no less obscene idea that the Jews themselves not only had to see to it that the damage was repaired but also that all monies proceeding from insurance claims were to be confiscated by the Reich was also Hitler’s; it occurred to him while he was lunching with Goebbels at the Osteria. Göring implemented this proposal in his own ‘Order on the restoration of the appearance of the streets by Jewish businesses’.

Whereas the two speakers at the 12 November meeting, Göring and Goebbels, sought to outdo each other in outlining perverse means of harassment – should Jews continue to be able to walk in German forests? What restrictions should be put on their use of railway sleeping cars? – Heydrich reminded them of the question they were there to discuss. He asked whether, in view of the fact that it would probably be eight or ten years before the last Jews left Germany, it wouldn’t make sense to provide them with a special badge. Göring ridiculed this suggestion – ‘A uniform!’ – and recommended for his part the construction of ghettos, which Heydrich rejected, however, pointing to the impoverishment and criminality to which that would lead. This went on, back and forth, for hours: in its brutality, cynicism and bureaucratic laziness in conceiving regulations whose sole goal was to destroy the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, the record of the meeting on 12 November 1938 was every bit the equal of the Wannsee conference in January 1942. 31

In the early afternoon, as the meeting was about to end, Göring indulged in a grim prediction of what German Jews could expect: ‘If within any foreseeable future the German Reich is involved in some conflict with another nation, it goes without saying that here in Germany we will think first of all of settling accounts with the Jews.’ Two and a half months later Hitler, in his notorious, often-cited speech delivered on 30 January 1939, which he later liked to claim was given on the day war broke out, said almost the same thing, but with significantly more aggressiveness and the crucial difference that he then immediately named ‘world Jewry’ as the instigator of a possible war: ‘If international Jewish financiers inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging nations once again into a world war, then the result will be not the bolshevization of the world and thus the victory of Jewry but rather the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.’ 32It was this poisonous symbiosis of madness and calculation that made it possible for the death of a legation secretary to become the pretext for the greatest organized pogrom in modern history.

‘I am reminded of what an Aryan in a Düsseldorf cinema experienced,’ we read at the end of the memoirs of Harry Kaufman, a young man who was able to emigrate in late 1938. ‘It was in 1937, when people were not yet so firmly convinced that Jews were to blame for everything. An insurance company was showing a promotional film about the consequences of a traffic accident. After the accident took place, on the screen there appeared in large letters the question: “And who is to blame for this?” A joker in the cinema shouted: “The Jews!” People laughed so hard that for several minutes you couldn’t hear a word.’ 33The mirth in the cinema gives us a good idea of the country’s mood on the eve of the pogroms: most people didn’t know what to make of anti-Semitic agitation. It probably wouldn’t do any harm to reduce somewhat the influence of Jews in economic life, as the government had already been successfully doing for years, and maybe it would actually be best for the Jews to leave Germany, sooner or later. But why this fervour, this strident rabble-rousing? After all, the Nazis’ conspiracy theories were sometimes positively ludicrous. The joker in the cinema had put it in a nutshell.

Читать дальше