Maria Christina Ramos - Mapping the World Differently

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Maria Christina Ramos - Mapping the World Differently» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mapping the World Differently

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mapping the World Differently: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mapping the World Differently»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mapping the World Differently — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mapping the World Differently», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

MAPPING THE WORLD DIFFERENTLY

AFRICAN AMERICAN

TRAVEL WRITING ABOUT SPAIN

Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americans http://www.uv.es/bibjcoy

Directora

Carme Manuel

MAPPING THE WORLD DIFFERENTLY

AFRICAN AMERICAN

TRAVEL WRITING ABOUT SPAIN

Maria Christina Ramos

Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americans

Universitat de València

Mapping the World Differently: African American Travel Writing about Spain

© Maria Christina Ramos

1ª edición de 2015

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-9134-164-2

Imagen de la cubierta: Portulano encargado por Carlos V

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

http://puv.uv.es

publicacions@uv.es

For my mother, who taught me the importance of feeling rooted, and for my father, who showed me the joy of wandering

Acknowledgments

It is my pleasure to thank some of those who made this book possible. First, I would like to thank Carme Manuel, general editor of the Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americans at the Universitat de València, for expressing interest in this manuscript and for generously providing me the opportunity to share this study of fascinating travel writing about Spain with readers. I would also like to acknowledge those who supported me through writing the dissertation from which this book evolved, including my director, Zita Nunes, and committee members for their engagement with this work. In addition, I am grateful to Smith College for the time and space for writing provided me through the Mendenhall Fellowship and to Daphne Lamothe in particular for generously reading some of the earliest chapter drafts. And I thank J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College, as well, for its support of my research.

I am particularly indebted to my friends who have urged me on along the way in the development of this project. Colleagues Ghazala Hashmi, Jane Rosecrans, Ashley Bourne-Richardson, and Bitsy Gilfoyle especially have provided a vibrant intellectual community that continues to sustain me amidst the inevitably heavy demands of the job. I also benefitted enormously from the good humor and camaraderie of fellow writers Michelle Brown and Jeannette Marianne Lee. And without the constant encouragement of dear friend and scholar Jennifer Hansen-Glucklich this project would never have been completed.

And finally, this book was made possible by the love and support of my extraordinary family. Many thanks to my parents, Oscar and Luisa Ramos, for, among other things, their unshakable confidence in me, and to my brothers Joe and Ozzie for gently pushing me to the finish line. Thanks to the beautiful Oscar James Carroll for his tremendous energy and inspiration. And, of course, my deepest gratitude and love go to my husband, John Timothy Carroll, for his patience, intellectual companionship, and loving partnership, all of which enrich my life immeasurably.

Portions of Chapter 2 were previously published in Geocritical Explorations: Space, Place, and Mapping in Literary and Cultural Studies (2011) and have been reproduced with permission from Palgrave McMillan.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION “A hunger to understand”

CHAPTER 1 Approaching African American Travel Writing about Spain

CHAPTER 2 “Moors as dark as me”: Mapping Spain in the Early Twentieth Century

CHAPTER 3 Frank Yerby’s Novel of Moorish Spain and the Trans-Mediterranean

CHAPTER 4 “Spain was baffling”: Locating the West in Richard Wright’s Pagan Spain

CHAPTER 5 A Stranger in Spain?: Lori Tharps’s Kinky Gazpacho

CONCLUSION

WORKS CITED

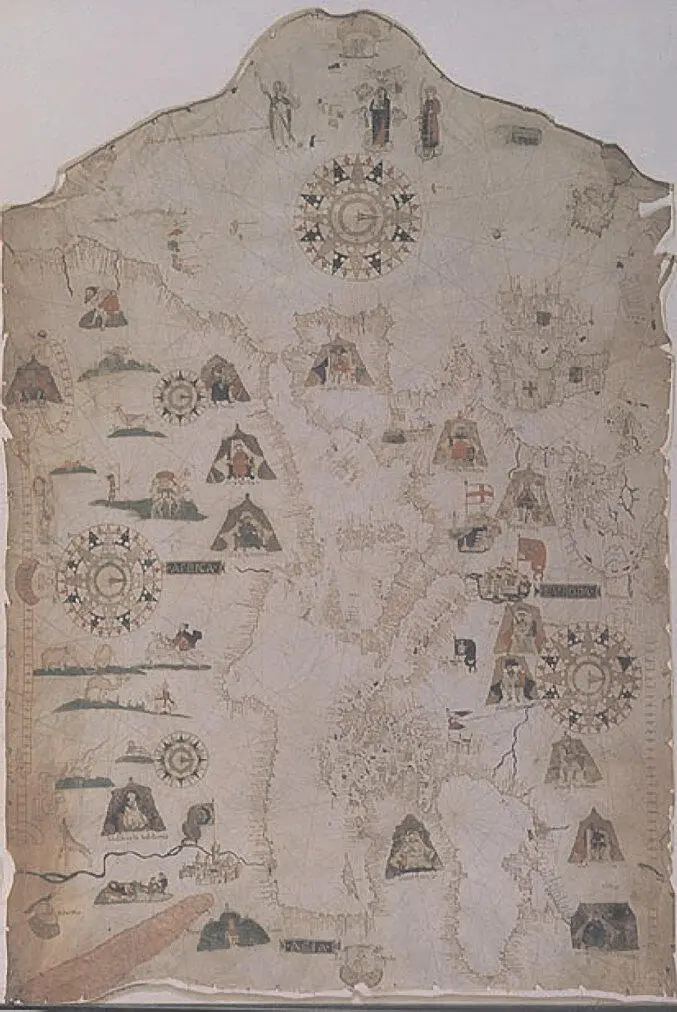

Portolan Chart of the Mediterranean World Mateo Prunes, 1559

Introduction

“A hunger to understand”

Richard Wright begins Pagan Spain (1957) with a portrait of himself in a car, staring at the Pyrenees ahead and trying to convince himself to cross the border from southern France into Spain. He explains that over the years numerous friends, not least among them, Gertrude Stein, had recommended he visit the country. Yet years later, when he finally travels to the border, he still hesitates to cross. Sitting in the car, steering wheel in hand, there is no physical or legal barrier preventing him from his journey—only a “state of mind” (3). The travelogue of Wright’s time in Spain in 1954 and 1955 opens not with a picture of physical movement, as one might expect, but with a compelling moment of contemplation. What is keeping him from entering “a Spain that beckoned as much as it repelled” (3)? Wright focuses our attention on the intellectual and emotional work his journey demands rather than the physical movement it requires. In this moment he is forced to consider what the idea of Spain means to him, what it will mean for him to travel its landscape and interact with its people.

Wright explains that his hesitation does not stem from fear of Spain’s totalitarian regime headed by General Francisco Franco. After all, he tells us, he had already experienced totalitarianism in the “absolutistic racist regime in Mississippi” and during his year in Perón’s Argentina (3). Indeed, one might even imagine that his travel in Spain would be freer than the experience of traveling as an African American in the U.S. at that time, particularly in the South. Wright points, instead, to another reason for why Spain is the “one country of the Western world” about which he wished not to “exercise [his] mind”:

The fate of Spain had hurt me, had haunted me; I had never been able to stifle a hunger to understand what had happened there and why. Yet I had no wish to resuscitate mocking recollections while roaming a land whose free men had been shut in concentration camps, or exiled, or slain. An uneasy question kept floating in my mind: How did one live after the death of the hope for freedom? (4)

Despite his hesitations, Wright reconciles himself to his journey and turns the car towards “the Pyrenees which, some authorities claim, mark the termination of Europe and the beginning of Africa” (4). So begins his travelogue of Spain. Wright’s account is more than a simple record of sites visited or a description of the customs and manners of a foreign culture. Rather, the introduction to his travel narrative suggests important personal and political consequences of travel, as well as a range of uses of the travel narrative; his difficulty with simply the prospect of travel in this passage suggests that there is more at stake in travel than we might at first assume.

Wright’s reluctance to cross the border into Spain seems to arise from the series of difficult issues he expects to explore through his travel. His desire to understand the “fate of Spain,” that is, its fall from a republic into a dictatorship at the end of the Spanish Civil War, is a quest to understand the failure of social democracy to prevail over oppression worldwide. 1 This failure, among others, defies Wright’s faith in humanism. His attention to the question of how people can “live after the death of the hope for freedom” reflects his increasingly pessimistic attitude regarding his ability to find a place in which to live and write freely himself. 2 And his investigation of both of these issues through Spain illustrates his belief that local phenomena can be used to represent larger global phenomena. 3 Wright’s journey into Spain, then, becomes a journey for understanding—understanding a personal issue (why thinking of Spain “hurt” and “haunted” him so), understanding a local issue (what accounted for “the fate of Spain” itself), and understanding a global issue (how did people live “after the death of the hope for freedom”). For Wright, travel could be a powerful enterprise, the effects of which had personal, local, and global implications.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mapping the World Differently»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mapping the World Differently» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mapping the World Differently» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.