“Skills” refer to what an individual needs to know in order for a practice to emerge and be sustained. Skills are also found, in a more abstract way, in the knowledge related to a practice. Thus, under the term “skills”, we can distinguish between physical abilities, know-how and knowledge.

The “material” element refers to what is tangible and mechanically or physically constrains or enables an action. This element groups objects and technologies (Reckwitz 2002; Shove and Pantzar 2005; Warde 2005) with infrastructure (Hargreaves 2011).

“Meanings” refers to “the social and symbolic significance of participating [in an action] at any given time” (Shove et al . 2012). This notion can be translated into the concept of the teleoaffective structure described by Schatzki (2005, pp. 42–55) or in terms of purpose and emotion, a form of goal-oriented engagement (Warde 2005).

Practice theories have been used to understand the emergence or to accompany the implementation of more sustainable practices (e.g. Hand et al . (2005), who study the evolution of hygiene practices and Gram-Hanssen (2010) who studies heating practices in relation to energy savings). Practice theories can furthermore be used to understand the emergence, maintenance or disappearance of practices at different scales: at the scale of a society (e.g. Shove and Pantzar 2005), or at a more individual scale, to understand how a particular practice is implemented by a particular individual or household (e.g. the practice of recycling in households (Fournier-Schill 2014)). Our chapter opts for this second approach in order to understand, at a micro level, what explains the existence and maintenance of the practice of eating together at the household level. The following section presents a qualitative study conducted for this purpose.

1.3.2. A two-stage qualitative study to understand how consumers “eat together”

The methodological challenge of our work is not so much in observation, or in revealing the existence and arrangement of practices, but rather in understanding their origin or their construction. Moreover, applying practice theories does represent a methodological challenge, as it can be tricky to accurately describe how an action is socially constructed (Hargreaves 2011). Our work is therefore exploratory and comprehensive in nature, which justifies the choice of a qualitative approach. The research methodology is composed of two stages, which serve to describe and understand the implementation of the “eating together” recommendation by consumers, in order to identify the skills, material and meanings on which it is based.

1.3.2.1. Step 1: Semi-structured interviews based on projective collages

The qualitative approach involves looking for diversity of practices, with the aim of understanding the mechanisms of adoption of these varied practices. Turrentine and Kurani (2007) propose a sampling method known as “illustrative sampling” which aims to ensure the diversity of the object studied. As our qualitative approach involves looking for diversity of practices, the first step of this sampling method consists of studying the determinants of the phenomenon (socio-demographic, motivations, etc.) in order to know on “which diversity” it is most relevant to base the selection of the individuals in the sample. For example, it has been shown that which socio-professional category an individual belongs to conditions their involvement in food (Plessz and Gojard 2014), which can impact the importance given to meals. Similarly, it is relevant to choose households of different “types” (e.g. a couple, friends sharing a flat, family with children, etc.), which seem to generate different practices (CREDOC 2017), just like the fact that the nature of the relationship with people at the table conditions food intake (De Castro 1994). Thus, we selected households of varying socio-professional categorues and size and where relationships vary: family relationships, roommates, etc. It should be noted that the approach does not aim to compare households with each other, but to determine which characteristics should be used to generate the most variability. The sample thus guarantees a variety of practices with respect to eating together by varying the age, the number of people in the home and whether or not there are children. Twenty-three participants were recruited via an Internet mailing list (Appendix, section 1.8).

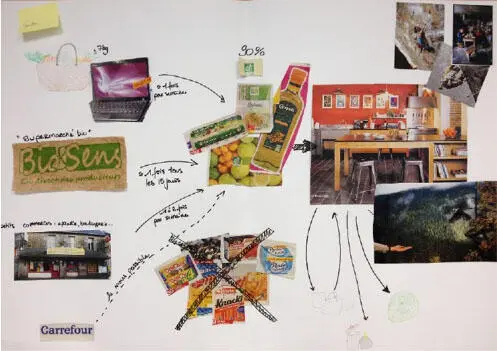

The projective collage method consists of asking individuals to paste together images to represent what they think or imagine about a situation or concept. Projective methods have been developed primarily as a dialogue facilitator. They are generally used to reduce bias, to study individual perceptions and to access unconscious processes or mental images in consumers. Collage allows consumers to express themselves without introducing bias.

In this study, the collage was used to provide respondents with a self-constructed discussion aid in a time prior to the interview, to address a topic (the organization of daily eating together ) which can be tricky to transcribe in an impromptu discussion. The poster was not analyzed as such.

To make the poster, participants were given a magazine. The participants were given the following instructions:

Make a poster that represents your food practices: from shopping to consumption, and represent what conditions your food organization. You have at your disposal magazines, cutting and pasting materials, and drawing materials. You have as much time as you want for this workshop. Once completed, we will discuss this poster, it will not be interpreted without your help.

The collages were made individually by each of the 23 study participants. Participants were only informed that the study was about eating practices, so as not to focus their attention on the issue of eating together .

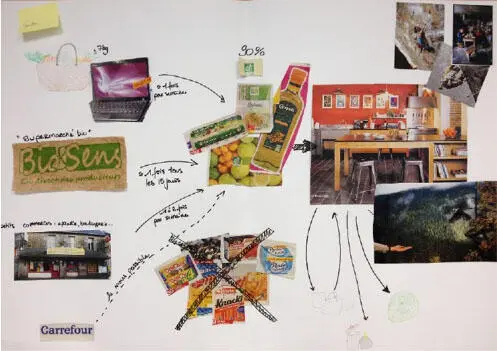

Participants took an average of 40 minutes to complete the exercise (e.g. Figure 1.2).

The collage method allowed us to recall and develop detailed descriptions of the individuals’ daily activities, and to know the links that connect them.

Following this creative phase, an interview was conducted with the support of the poster. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. Non-targeted thematic coding was conducted in an exploratory approach. The coding was carried out by continuous thematization, which amounts to constituting the themes as the interviews were analyzed, which were taken in the alphabetical order of the participants’ names. The analysis was based on this coding in order to identify the different practices of eating together and to characterize the elements necessary for their implementation.

In order to understand the context in which the described practices are embedded, the projective/discursive collection is combined with an observed/discursive data collection, as presented below.

Figure 1.2. Example of a projective collage (Paola). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/seredelanauze/evolution.zip

1.3.2.2. Step 2: In-store and at-home observations

Approximately one year after the collages/interviews (the length of time that allowed for analysis of the collages/interviews), observations/interviews were conducted during 1) grocery shopping and 2) a meal in the home and its preparation and storage. 11 of the 23 participants from Phase 1 took part in this phase. These observations, although one-offs, made it possible to objectify the facts related in the first interviews (e.g. to see what a participant meant by: “my kitchen is very small”) and provided a contextualized overview of what was described in the first interviews. Ideally, the interviewer visited the participants’ homes before they left to go shopping, so that they could travel from home to the grocery store with them. In cases where it was not possible to meet at home, the meeting took place directly at the store.

Читать дальше