– reduce obesity and excess weight among the population;

– increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior at all ages;

– improve dietary practices and nutritional intakes, particularly in at-risk populations;

– reduce the prevalence of nutritional diseases.

An assessment of the achievement of these objectives was carried out in 2006–2007 via the Étude Nationale Nutrition Santé (Castetbon et al . 2011), supplemented by the Étude Individuelle Nationale des Consommations Alimentaires (INCA2, National Individual Food Consumption Study (Afssa 2009)), the Baromètre santé-nutrition (Health and Nutrition Barometer) and regional studies (HCSP 2010). These assessments revealed that the objectives had only partially been achieved and that the program needed to be strengthened to continue to promote the desired behaviors (e.g. only a very slight increase in the purchase of fruits and vegetables had been observed) (Hercberg 2006). From this observation, the PNNS2 (2006–2010) emerged.

At the end of the PNNS2, the evaluation report noted that the expected results had not been obtained (particularly in terms of obesity screening (IGAS 2010)). This report recommends, among other things, revising the feasibility of certain objectives, correcting the formulation of certain principles that are sometimes the source of a binary vision of nutrition (“good” vs. “bad” products) and systematically citing the programs with which the PNNS is linked for better coherence between the public policy programs (Menninger et al . 2010). The PNNS is also criticized for not taking sufficient account of local specificities or social groups, which risks stigmatizing certain sectors of the population (Poulain 2006). For example, the PNNS3 includes a special section on overseas territories and emphasizes the importance of social, economic and cultural determinants of diet. This version explicitly emphasizes that it aims to banish “any stigmatization of people based on a particular dietary behavior or nutritional status” from the PNNS (Ministère du travail, de l’emploi et de la santé 2010). The PNNS3 also ensures overall coherence with other national food programs (such as the Programme National pour l’Alimentation (French National Food Program) resulting from the law on the modernization of agriculture and fishing, as well as the Obesity Plan, of which the PNNS is a component (Chauliac 2011)).

From its first version, the ambition of the PNNS was to “take into account the biological, symbolic and social dimensions of the food act” (Chauliac 2011). Thus, “eating well”, a concept that is more encompassing than “nutritionally healthy eating”, takes into account the social dimensions of eating and includes eating together in its program. However, eating together is not explicitly addressed in the evaluation. It is mentioned in the general parts of the reports, such as the preface, the foundations or the objectives of the program, but is not the subject of any explicit recommendations in the same way as there are consumption guidelines for fruit and vegetables, dairy products, etc. Despite this, on the Manger Bouger website, a section asks the question “Why is it important to get together for regular meals?” 1 . Eating together is therefore a more comprehensive practice of balanced nutrition, and is more in line with a balanced lifestyle. Indeed, eating together is beneficial for several reasons:

– promoting the structuring of meals (starter–main course–dessert), which itself promotes nutritional diversity;

– avoiding skipping meals;

– taking the time to eat (favorable to better digestion and a better perception of the signs of satiation);

– cooking fresh products (healthier than processed products, which are generally saltier, more fatty and less natural).

In France, despite the fact that the conviviality of meals remains central among the discourse of the French population (Mathe et al . 2014), eating together is less and less in line with the evolution of lifestyles, affected in particular by demographic changes (e.g. composition of households, activities of their members) or changes in food supply (e.g. prepared and individualized dishes). The INCA2 study published in 2009, based on data collected in 2006 and 2007, highlights a trend towards a destructuring of eating patterns among the youngest members of society (15–35 years), which has been increasing since 1999.

Similarly, it is clear that the time spent in front of screens and the solicitations of smartphones at all hours of the day and night can interfere with maintaining time to eat together , parasiting the interpersonal relationships essential to conviviality. The INCA3 study (Anses 2017) emphasizes that the time spent daily in front of screens (excluding work time) is constantly increasing, with an average increase over the last 7 years of 20 minutes in children and 1 hour and 20 minutes in adults. As a result, eating together is not self-evident, and more support is needed.

In conclusion, eating together is at the heart of the PNNS’s concerns but is not the subject of accompanying measures, and current lifestyles make it difficult to maintain this practice which contributes to a healthy lifestyle. Faced with this observation, a study of the different practices of eating together and a reflection on the conditions of implementation of these practices are necessary.

1.3. Understanding the emergence and maintenance of eating together

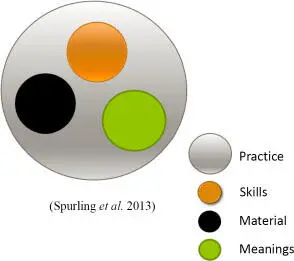

This section adopts a practice-based approach to study eating together from a holistic perspective, that is, by taking into account all the elements related to the existence of practices. These elements are the material conditions, the necessary skills and the meanings associated with the emergence or maintenance of the practice.

1.3.1. Benefits of practice theories to the study of eating together

Practice theories are a set of theories and concepts whose principle is understanding everyday and routine activities by studying the emergence of practices as a result of the context rather than by analyzing the choices made by individuals to arrive at a behavior. Schatzki, a founding author of this theoretical trend, inherited from the work of Bourdieu and Giddens, defines practices as sets of activities that involve and are linked by knowledge, skills, meanings and material elements (Schatzki 1997). Reckwitz, another seminal author, positions himself in relation to Schatzki’s ideas by adding the study of habits and routinized actions. Reckwitz (2002) defines practices as a type of routine behavior that consists of several interconnected elements: forms of bodily activities, mental activities, “things” and their use, accumulated knowledge in the form of understandings, skills, emotional states and motivational knowledge. Thus, social practices are taken as the unit of analysis; individuals are considered to be “carriers” of practices.

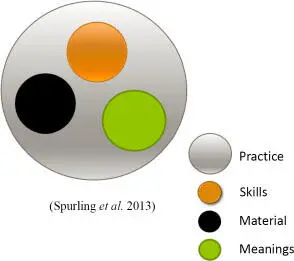

Shove et al . (2012), building on the seminal work of Reckwitz (2002), propose a simplified framework to empirically explain the emergence, maintenance and demise of practices. According to this framework, a practice emerges and is maintained as a result of a combination of three elements: skills, meanings and materials (Shove et al . 2012) ( Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Diagram of the conceptual framework from Shove et al. (2012), as presented in Spurling et al. (2013). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/seredelanauze/evolution.zip

Читать дальше