1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...17 Before entering The Study, my I.Q. had been tested and the results emboldened Biddy to take a few radical measures. I started skipping classes to be able to participate in piano competitions. I also started to skip whole years and ended up graduating with girls three years my senior. How I ever passed all my exams is a mystery, as I had been forced to miss so many of the lectures. But, once again, I was fortunate: most of the teachers were indulgent and perhaps a little sympathetic as well, helping me along while trying to keep me as level-headed as possible. For me, going to school was a joy and an escape – almost a holiday – and a welcome respite from what was becoming, after the first euphoric months at V.D., the increasingly stressful hours at the piano. Indeed, signs of stress were definitely showing; before every performance I was becoming physically ill, throwing up uncontrollably, much to the consternation of those around me. I soon learned to keep this disgusting occurrence secret, never panicking since I knew I’d feel fine once on stage.

When I was eleven, it was time for me to start lessons with the master pedagogue, Yvonne Hubert, who came to V.D. on Fridays to teach the advanced students. Biddy, who sat with me and supervised my practising every day, and Soeur Stella, who taught me twice a week, had prepared me well so that my lessons with Mademoiselle Hubert were quite thrilling. A tiny little Piaf-like French woman whose breath always smelt of the gallons of coffee she drank, very highly strung and very serious, she had settled almost by accident in Montreal years before and became the most revered piano teacher in Canada. She had been a pupil of the legendary Alfred Cortot and, among her many gifts, she possessed the most extraordinarily agile left hand. Never demonstrating with both hands, she would sit on my right side and play everything miraculously with her left hand alone – a feat that never failed to amaze. A perfectionist, she instilled in me a desire for clarity, structure, and intelligent music-making. Her students produced mostly lovely sounds – they never banged – and she counted among them at that time André Laplante, my great friend William Tritt, whose brilliant career was tragically cut short by his premature death, then, a little later, Marc-André Hamelin and Louis Lortie, who are now pursuing major international careers.

Great rivalries grew up not only between the students but also between their black-robed teachers. As there were many national and international competitions taking place in Montreal, the rivalries thrived, but for the most part (at least among the students) they were amicable and beneficial. One little nun, though, was quite enterprising; she actually hid in the broom closet of the room where an international jury was deliberating so that she could get advance notice of which pieces her pupils would, potentially, be playing in the next round. She also gave her students little snorts of brandy before they went on stage. Sometimes, when she decided the pupil seemed lethargic, it became more than just a sip or two … which made for some wild performances.

Biddy, however, had her own agenda, and remained unfazed over whether I won or lost competitions. Of course, she was pleased when I won, but what concerned her most was the quality of my playing and that it should deserve to win (my father George, on the other hand, just felt I deserved to win everything regardless). She was not your typical stage mother because she never pushed me to perform in public and, for two years, much to the good nuns’ horror, she refused to allow me to enter competitions or to perform at all, insisting I use the time to learn repertoire and to develop my technique. Probably I was very overworked at the time and there was never really any break, since even holidays in Europe now consisted of daily searches for pianos on which to practise in hotel bars and restaurants, piano shops, even night clubs – a nightmare for me as I was convinced my playing was obtrusive and annoying to other guests or to the staff. But Biddy was adamant that I put in the hours every day.

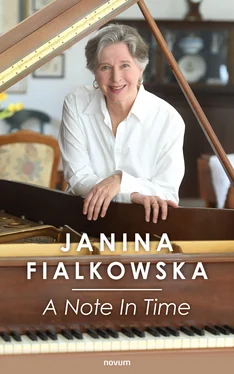

Although holidays had lost any vestige of relaxation and the pressures of work were increasing at home, I still felt quite content most of the time. I was sure I could cope with everything and was proud to be able to do so, convinced I was enjoying my life. Nothing made me happier than having good music lessons, getting good marks and being no trouble to my parents. But there were dark shadows lurking: a few early indications of the discrimination I was to suffer in later years at the hands of the occasional xenophobic, separatist-inclined French-Canadian organisations made their appearance. Even as a child I was often overlooked for performance or prize opportunities because of the political incorrectness of my surname. Janina Fialkowska is a very Polish name and didn’t fit into the French-Canadian philosophy of the 1960s. Neither was it particularly popular with the arch-Anglo society of Toronto at that time. I may well have not noticed the occasional unfairness, but my parents suffered mightily on my behalf, and it was their suffering that hurt me.

I was still a confident and cheerful soul back then, however, even with my terrible pre-performance nerves. I had discovered early on how to compartmentalize different emotions in different parts of my brain, locking away the more unpleasant aspects of life quite successfully during the greater part of the day. Playing the piano was just something I did better than most children of my age, and I enjoyed the distinction it gave me. I realised that to remain at the top was a struggle and the work had to be done, but my fundamental passion for music had yet to be ignited.

I was already studying with Yvonne Hubert when Arthur Rubinstein came to Montreal. The first time I heard him play, in the mid-sixties, he performed Mozart’s concerto K. 466 and Beethoven’s Emperor concerto with Zubin Mehta conducting the Montreal Symphony. The following year he returned and played the Schumann and the Chopin E minor concerto, again with an admirable accompaniment from Mehta. Each piece was sublime, but it was the Chopin that was a revelation for me. I had never heard playing like this – not only the sound from heaven, the burning emotion, lyricism, divine phrasing, and structural perfection, but the fact that Rubinstein communicated all this incredible beauty to me, so personally. I was transported. That night I wrote succinctly and accurately in my little diary: “Thank you Chopin and thank you Arthur Rubinstein – now I understand what it means to be a musician.” From then on my whole attitude changed; music was now a noble profession in my eyes, not just a child’s game or a mother’s ambition, and I intended to strive as hard as I could to be worthy of its responsibilities and demands.

But then Peter was sent off to boarding school. I missed him desperately and practising piano began to overwhelm my life. I now went to school only to attend classes for the ten subjects I needed in order to pass my Matriculation. Recess, sports, school outings, Girl Guides, debating clubs, language clubs; all extra-curricular activities were banned from my life, and as I was practising five or six hours a day it was only at night that I could escape a little into a fantasy world. There was a streetlight that cast a beam onto my bed, and I would stay up into the wee hours reading exciting books by Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas and P.C. Wren, Sienkiewicz and later, Tolstoy. It is only in retrospect that I wonder how I survived it all. Biddy was less fortunate: driving me hither and yon to lessons, arranging extra tutoring for me in certain subjects, and bringing me to competitions all over the province, as well as sitting by the piano and practising with me every day – all this began to take its toll. During my early to mid teens, she had several serious operations to remove suspected tumours and illnesses. One massive depression confined her to a hospital for months at a time. George was amazing, coping admirably, visiting Biddy every day, running the farm, cooking for me and being there for all of us. By this time, I had so much discipline instilled in me that my work barely skipped a beat. Besides, I knew that what would please Biddy the most would be if I continued working as hard as I could. I missed her but it was also pleasant and relaxing to be just with my father, whom I adored. We would cook together at night, go to concerts, and he would help me in the evenings with my algebra and geometry homework. I remember those evenings with great nostalgia.

Читать дальше