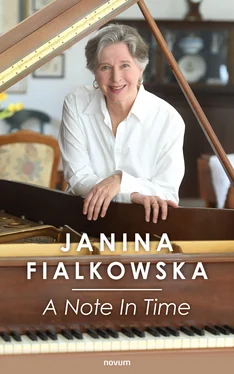

My mother, Bridget or “Biddy,” was the youngest of three sisters. Incredibly strong-willed, like my grandmother, she seems to have been totally unsuited to the life she was expected to lead. Many of her early years were taken up in the pursuit of fun, since there were continuous house parties with masses of young people in their home, riding, playing tennis and hockey, acting in amateur theatricals, travelling luxuriously, and leading a life of utter ease. But my mother, early on, apparently developed a strong streak of rebellion, hating her governess–ruled education and desperately wishing she could go to a “regular” school and university to earn a degree and follow a profession. She refused to be a “debutante” and at the age of nineteen, while the family was spending a year in Paris, she suddenly decided she wanted to be a pianist. She enrolled herself into the École Normale de Musique which, at that time, boasted such luminaries as Alfred Cortot and Nadia Boulanger amongst its faculty, and she worked frenetically and fanatically for four years, until 1939 when the family, for obvious reasons, could no longer allow her to remain in Paris. Reluctantly my mother returned home, and her musical career was put on hold indefinitely … or at least until I appeared on the scene. Her only non-musical interest during those Paris years was ice hockey; she played Centre Forward in the European Woman’s Hockey League representing Great Britain, but then defected to the French team.

When her fiancé was killed in the early months of the war, my mother enlisted and earned a degree as a mechanic. She was sent overseas with the armed forces and, once in England, was assigned as a driver/mechanic to the Polish forces in exile stationed up in Scotland, which is where she met my father.

During the early stages of World War II, the Poles were hugely popular in Britain, especially after the heroic performance of the Polish pilots during the Battle of Britain. However, once Hitler had attacked the Soviet Union and Stalin became Britain’s ally, the Poles became somewhat of an embarrassment to the English and American governments who desperately wanted to keep Stalin appeased and the Russians fighting hard on the Eastern front. With Poland occupied by Russian troops who had no intention of leaving, what followed was a tragic betrayal on the part of the allies. It wasn’t that anti-Polish sentiment became government policy, but it certainly wasn’t discouraged in any way, and it flourished amongst left-wing groups in England and Scotland.

And so it happened that one day my mother, sitting in her truck with the window open, waiting to drive a Polish officer to a staff meeting, was spat upon and insulted by a young Scot. My mother returned to the officer’s mess that evening and recounted her story. The Polish officers, who doted on her, made a huge fuss, exclaiming that they would never forget how she had suffered for Poland etc. etc. – all the officers but one, who had just arrived and who was unknown to my mother. His only comment was that perhaps the next time she went out she should take an umbrella! Thus, my parents met, and two years later they were married in London, where they both had been transferred. My mother had become so proficient in the Polish language that she was assigned to the Polish headquarters in the Rubens Hotel, where she served as a translator for the Polish Underground Army.

As I’ve mentioned, my mother was obsessive, quite unreasonable and, on occasion, a bit of a tyrant. But she had a wonderful sense of humour and a wicked sense of fun. A lifelong rebel, she enjoyed flaunting orders, driving through red lights, backing up on major highways when she missed an exit, jumping to the head of queues with panache, and filling out serious forms with witty and thoroughly disrespectful comments. Even in her late seventies, when she was under strict instructions to stay indoors because of a bout of pneumonia, she sneaked out and went skating on the lake in front of our house because, as she put it with her own infallible logic: “The ice was so perfect.” And just to annoy all of us, she recovered from her pneumonia the next morning! She was exasperating, but I loved her.

Of my father’s family I know far less, my father not being interested in such things. All I know is that my grandfather was a Pole who came from the Austrian section of Poland (Poland before World War I was divided into three occupied sections: the Russian sector, the Austrian sector, and the German sector) and that he was fortunate enough to come from this more tolerant section, where he had a successful career in the military, becoming the Commandant of the Austro–Hungarian officers’ school in Wiener Neustadt and eventually rising to the rank of General. He married his best friend’s daughter, Ludmilla von Regwald, whose family owned great tracts of land in Bukowina as well as in Poland. An alleged bon vivant, full of charm, he died suddenly in 1919, leaving my grandmother destitute with three small boys, the war having devastated the family finances.

My father Jerzy, or George, was the youngest son and only eight years old when his father died. They were living in Lwów (formerly Lemberg), where times were terribly hard following not only the horrors of the first World War, but also the failed attempt to re-occupy Poland by the Bolsheviks in 1920–1921, when my uncle Konrad, still only a young boy, acted as a courier for the resisting Polish forces. At one time the family survived only with the help of the American Red Cross and their soup kitchens. But the Fialkowski boys were all over-achievers, and by 1939 my uncles Konrad and Gabriel were already successful doctors of medicine and heads of hospital departments. My father was an electrical engineer with a bright future, working for the German firm of Siemens in Warsaw. Called up to active duty after Poland was attacked by the Nazis, he took part as a young reserve officer in the defence of Warsaw, where the sadly under-equipped Polish army heroically staged the last cavalry attack of modern history against the German tanks. He then was ordered to evacuate and re-join the Polish army in exile. Through many hair-raising adventures, including dodging bullets, avoiding bombs and a daring escape from a prison camp in Romania, he made it to Greece, where he apparently had a marvelous few days sightseeing before embarking on a transport ship to France. My father had a passion for travel, and nothing made him happier than visiting exotic places, preferably in warm climates (even in the middle of a war!). After France he finally ended up in London via Scotland. During the war, he worked in the Polish underground as a communications expert.

Miraculously, my strong-willed grandmother and two uncles survived both the German and Soviet invasions, my uncle Konrad having been interned by the Gestapo and later persecuted mercilessly by the post-war communist regime. My uncle Gabriel, although a less intense, more happy-go-lucky fellow, also suffered mightily from deprivations and persecution; among other things, his home in Lodz was first commandeered by retreating German troops and then by Russian troops, who he found had chopped up all of his furniture to use for firewood! The rest of the family – cousins, uncles and aunts – were either killed or deported to camps, Nazi or Soviet. Some survived and one, a resistance fighter, escaped to South America after the war, but was hunted down by the communists and assassinated. My father spent over seven years without knowing if his mother was dead or alive, and only ventured back to Poland to see his family in 1958, after Stalin had died. Had he returned earlier he would most likely have been shot.

Читать дальше