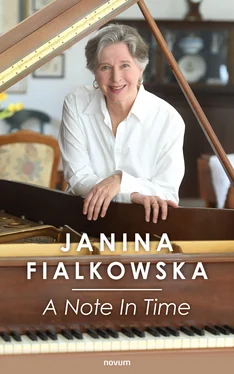

I decided these thoughts were counter-productive and tried to concentrate on anything else. When my mother lay dying I would “give” her happy memories to think about. I tried out this tactic on myself and thought of our recent trip to Paris, of our walks in the mountains, of pieces by Chopin, the composer to whom I feel closest, whose music speaks directly to my heart, affecting my emotions with an almost preternatural power.

Finally, around 5:00p.m. I was ushered into the freezing cold, rather shabby operating room. It was such a relief to actually have the endless waiting over that my good mood instantly returned and I chatted happily with the kind nurses and with the anesthesiologist, who had me laughing just before he put me under.

“Ms. Fialkowska!” A voice woke me out of the troubled sleep into which I had slipped. Most of the other patients had either gone home or had been transferred to other wards. Harry was standing by my bed smiling at me with anxious eyes and Dr. Morris was speaking to me. She looked exhausted and was still wearing the blue “shower cap” that surgeons wear, and which looks ridiculous on most but not on her. I wasn’t taking in all she was saying but the message was clear and blunt. I had cancer; the tumour had to be removed.

She spoke of radiation therapy, of chemotherapy, and I tried to comprehend and to be brave. Above all, I kept telling myself not to make a fuss – not to make it difficult for her – for Harry. She said that we would have to discuss how to proceed but that she would first confer with her colleagues about how best to save my arm. I had only one question: would I be able to play the piano after the operation? She couldn’t give me a definite answer and left soon afterwards.

It was close to 7:00 p.m. and I was to be discharged soon. I felt in complete turmoil and very ill. The tubes in my nose and in my wrist and the large cuffs wrapped around my lower legs to enhance circulation started to prey on the more neurotic segments of my brain. I felt as though I was being buried alive. The combination of lack of food and the anesthesia made me feel dizzy and nauseated. My heart started to race. Suddenly there was a loud, fast and scary beeping coming from the monitor by my bed. A cardiologist was hurriedly summoned, and something was adjusted in the intravenous medication.

There was now no question of my returning home that night, and I lingered for hours in the recovery room, drifting in and out of an uneasy sleep. Harry was finally told that I was out of immediate danger and that he should leave and come back for me in the morning. Upset and distracted by the events of the day, he drove home alone in the storm. He had only been to New York a few times in his life, and had never negotiated the trip in and out of the city. My concern for him was so great that I temporarily forgot my own predicament – an effective counterirritant, I thought to myself, and smiled wanly for a few seconds before slipping back into self-absorption.

Would I ever play the piano again?

Chapter 2

Scenes from Childhood (“Kinderszenen”) by Robert Schumann

My first public performance was not what one could term an unmitigated success. History relates neither the obstetrician’s nor the nurse’s reaction to my initial appearance on the world stage in 1951 but, according to family legend, the first words which fell from my mother’s lips following my birth were: “Oh God! Take it away! That’s not a baby – it’s a dried prune!”

Presumably such a remark, inflicted at such a tender age, could damage a person’s psychological makeup for the rest of their life. But this kind of wickedly humorous honesty was a family hallmark and therefore part of my genetic code. At home remarks that would send others scurrying to psychoanalysts were nonchalantly absorbed on a daily basis; to survive one needed to develop either a very thick skin or the capacity for lengthy periods of selective deafness.

That said, there really is a strong streak of eccentricity in my mother’s family that, coupled with a tendency to obsession, makes for an interesting agglomeration of personalities. To mention but two, I had a cousin who, at age seventy, streaked down one of the main streets of Victoria, British Columbia, stark naked, hand in hand with one of the most notorious town prostitutes, because he felt it was an amusing thing to do. And another cousin, a dear, loveable person who, for the Queen Mother’s 100th birthday, sought out and bought the very outfit Her Majesty wore on the day of her celebration, put it on, had his photograph taken proudly wearing it, and then sent copies of the photo to all of the members of his family as well as to Clarence House. But then, my own mother, having received a hand-knitted tea cozy as a wedding present from an elderly friend, decided it was far more suitable as headgear than as a pot cover, and for years wore it during the winter months without a trace of embarrassment. The scary part is that the family found nothing remotely odd in this behaviour.

In addition, the women of my mother’s family have tended to be strong-willed and bossy. And when, by some quirk of fate, there is a member of the family with a slightly more normal (boring?) outlook on life, chances are this poor person, feeling somehow inadequate and at a disadvantage, will seek out a glorious eccentric in marriage just to keep up the family’s reputation and pass the interesting genes on to the next generation. As for myself, the obsessiveness and strong will are definitely there; and eschewing a life of leisure for never-ending hours of struggle in front of a black box with white keys, could be interpreted as mildly eccentric.

We are definitely proud of our “oddness” – no question about it. But when the human cocktail of eccentricity and obsession is mixed with despotic tendencies, the result is sometimes a rather entertaining, perhaps rather overwhelming personality; my mother instantly springs to my mind.

The genealogy of my maternal grandmother is a typical Canadian mixture of Scottish and English adventurers who rose in the ranks of the Hudson’s Bay Company and made their fortunes. One of them, Robert Miles, my great-great-great-grandfather, actually became chief factor of the company and married a remarkable lady from the Cree nation. It has always been a source of great pride to know that I have some First Nations blood running through my veins.

The marriage of Robert and his wife, Betsy, was happy and successful, and their grandson, my maternal great-grandfather, rose to prominence as a great financier, becoming president of the Bank of Montreal and founding the Royal Trust Company of Canada. For his efforts, he was knighted and thereafter was known as Sir Edward Clouston. He was obviously a bit of a rogue, but he enjoyed life and was a kind and philanthropic man, particularly towards his less fortunate relatives, who regarded him always with great affection.

Sir Edward had three daughters; two died very young, and the third, Marjory, was my grandmother. An extraordinary beauty, she also appears to have been extremely strong-willed, especially in her choice of husband. Having been brought up in the lap of luxury and as part of the cream of Canadian Society (such as it was at the end of the 19th century), she was expected to make a high-profile marriage, preferably to a titled Englishman or, at the very least, to someone from a family of equal wealth and power. She chose, instead, a persistent suitor from Victoria who was a “mere” Doctor of Medicine. Although her parents overcame their initial prejudice, some of her other relatives and friends were aghast. The fact that my grandfather was one of the most renowned and decorated research scientists in his field didn’t sway them one bit. In just three generations the family had gone from carrying canoes in the wild and trading fur pelts, to considering an alliance with a professional man as a social faux-pas and a definite “step down.” My grandfather, a parasitologist, had already distinguished himself as a young man with his work in Gambia and the Belgium Congo, isolating the tsetse fly as the carrier of the dreaded “sleeping sickness.” Shortly after the First World War, he was sent to Poland, where a terrible epidemic of typhus was raging. For his magnificent work there, he was given Poland’s highest civilian decoration. Decades later, in 1976, when I was engaged to perform three concerts with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, I spent a day as an honoured guest at the renowned Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The fact that I was a concert pianist was considered all very worthy, but the delightful attentions and kindnesses that I received from the Dean and the professors were mostly due to the fact that I was the legendary Dr. John Todd’s granddaughter.

Читать дальше