1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...19 Nowadays, Ontario has a language policy based on a territorial system in which parts of the province where French is spoken by a given minimum proportion of the population are considered bilingual and services have to be offered in French as well as English. Communications from the provincial government to the population as a whole generally happen in both official languages (e.g. the government website is bilingual). However, the right to French language services only exists in designated areas. An area can be considered bilingual when 10 % of its population is made up of Francophones; urban centres must have at least 5000 Francophones. Twenty-five areas are currently designated bilingual. They are found all over the province, and include urban municipalities such as Toronto, Kingston, Windsor, Sudbury, and London. The National Capital Region is also designated bilingual in separate legislation. The language political situation is in constant flux, as evidenced, by way of example, by recent calls to include French in the emergency child abduction alert system ‘Amber’ (Branch, 2016a). French schools exist throughout the province, but in higher numbers where francophone residents make up a certain proportion of the population. Immigrants generally have freedom of choice regarding the school system (i.e., its medium of instruction, English or French);2 the arrival of Syrian refugees in Ottawa in 2015 resulted in 7 % of them opting for French schools, a development deemed significant enough to have made it into the French-language press (Branch, 2016b).

The province of Ontario does not have statutory official languages. The French Language Services Act 1990 gives everyone the right to use both languages in the legislative assembly (s 3(1)), stipulates that bills and acts shall be introduced and enacted in both languages (s 3(2)), and that pre-existing acts shall be translated (s 4). There is a right to receive ‘available services’ in French from the provincial government in designated areas (s 5). In these designated areas, citizens have these language rights with regards to municipal government as well (s 14), and there is a French Language Services Commissioner (s 12) that oversees compliance with the act. The act’s preamble, however, does mention that ‘in Ontario the French language is recognised as an official language in the courts and in education’; education is now available in the public system, with five secular and nine Catholic school boards that operate in French. There are French colleges and some of the province’s universities offer instruction in French. Ontario is home to the largest Francophone population outside Quebec, with just under half a million. This is more than in New Brunswick, although Francophones account for a third of the population in that province (see section 2.4).

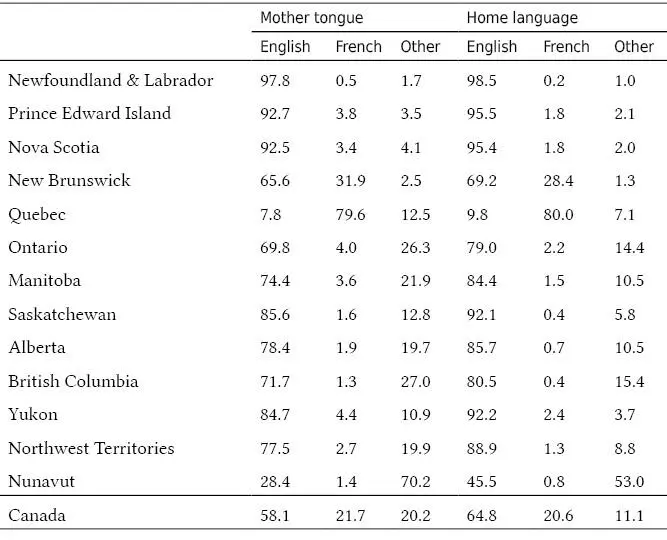

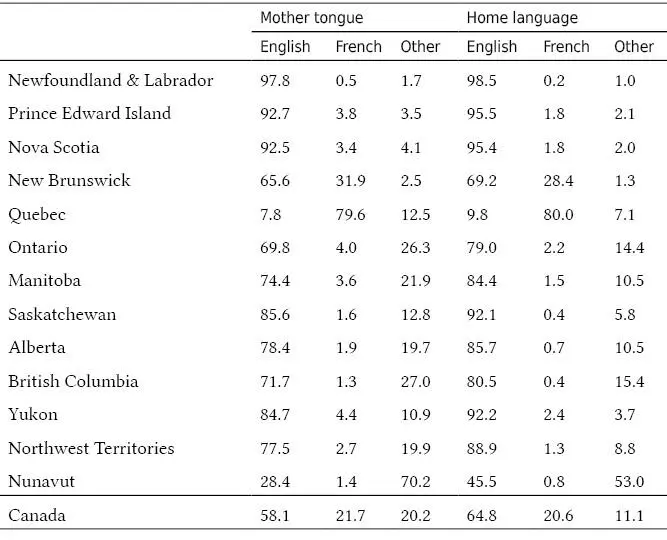

Table 2.1: Percent of responses to mother tongue and language spoken most often at home (single mother tongue responses only, i.e. excluding respondents indicating more than one mother tongue), in the 2011 census, by province/territory.

To conclude this section on ‘English’ Canada, it is worth pointing out the presence of many non-official languages in these provinces, like in the rest of the country. Anglophones are clearly the dominant group, but in all provinces except Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Quebec, it is the speakers of languages other than French, taken together, that come second in terms of demolinguistic weight. Table 2.1 illustrates this. These so-called ‘Allophones’, whose mother tongue is neither English nor French, account for a fifth of Canada’s population, only 1.5 percentage points behind Francophones, a lead only due to the large French-speaking population of Quebec. The difference is most obvious in the provinces west of Quebec; the Maritime provinces (NL, PEI, NS) all have above 90 % Anglophones. The home language offers another glimpse into the English-dominant nature of the ‘ROC’: over 95 % of respondents in the Maritimes use mostly English at home. In Ontario, Western Canada, and the Territories, English also benefits from a shift away from both French and non-official languages. Only in Quebec is the shift from mother tongue to home language also benefitting French, though more Allophones shift towards English. The high number of ‘Other’ languages retained in the home in Nunavut is explained by the vitality of the two aboriginal (and official) languages Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun: 68.5 % had it as their mother tongue, and 52.2 % claimed to use it as their main home language. Nonetheless, English is popular, since the 28.4 % mother tongue Anglophones are outnumbered by the 45.5 % for whom it was the language spoken most often at home. The special status of these aboriginal languages will be taken into consideration next.

2.2.3 Aboriginal languages and their limited role in official settings

The Ethnologue database lists 94 individual languages in use in Canada. Besides the two official languages English and French, this includes 17 non-indigenous languages and 77 indigenous ones (Lewis et al., 2016). The aboriginal languages themselves come from several distinct language families, including Eskimo-Aleut, Na-Dené, Algic, Iroquoian, Siouan, Salishan, Wakashan, and Tsimshianic. According to the 2011 census, the ten languages spoken most widely are Cree (an Algonquian language, 95165 users), Inuktitut (Eskimo-Aleut, 36240), Ojibway (Algonquian, 24770), Dené/Chipewyan (Athabaskan, 12845), Innu/Montagnais (Algonquian, 11380), Oji-Cree (Algonquian, 10160), Mi’kmaq (Algonquian, 8855), Atikamekw (Algonquian, 5980), Blackfoot (Algonquian, 4360), and Stoney (Siouan, 3475).

Three groups of Aboriginal peoples are commonly distinguished in Canada: the First Nations, the Inuit, and the Métis. The Métis are descendants of early mixed unions between European (typically French) men and Aboriginal women who, over time, developed a distinct cultural and linguistic identity; they are found throughout the country, particularly in Alberta. The Inuit are part of a circumpolar people also found in Greenland and Siberia; in Canada they are found mostly in Nunavut, where they are a majority, and in the Nunavik region of Quebec. There are also smaller groups in the Northwest Territories (Inuvialuit) and Newfoundland and Labrador (Nunatsiavut, northern Labrador). The First Nations comprise all Aboriginals who are neither Métis nor Inuit. They form the largest population (851560) of the three groups, almost twice as large as the Métis (451795), with the Inuit (59445) a distant third.

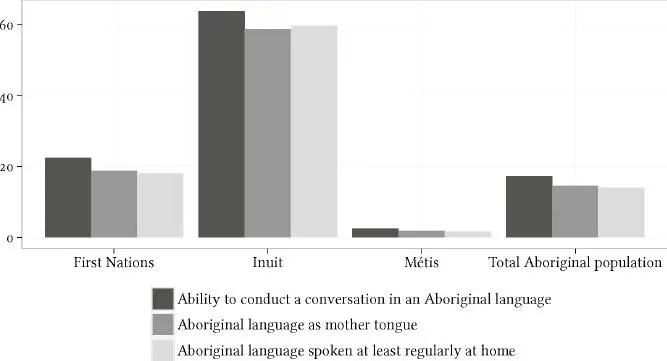

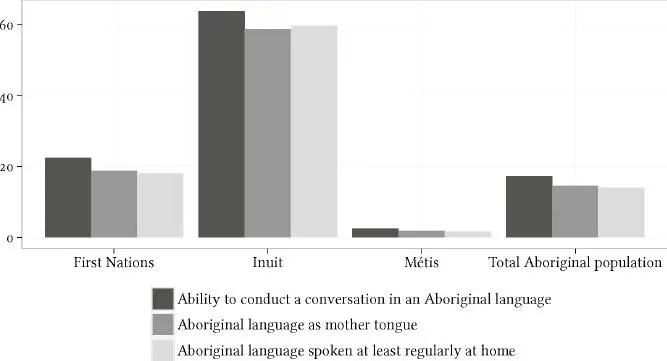

Figure 2.3: Proportion (percent) of Aboriginal population by language use (National Household Survey 2011).

The 2011 National Household Survey gives information on the language abilities of the three groups. The data, visualised in Figure 2.3, reveal differences between conversational, mother tongue, and home language status, as well as between the three types of Aboriginal peoples. The Inuit have the highest ability, well over 50 % for all three kinds of language use. The Métis do worst, with a maximum of 2.5 % being able to conduct a conversation in an Aboriginal language.1 The First Nations range from 22.4 % conversational ability to 18 % home language use.

The sporadic contact between Aboriginal Canadians and Europeans that took place in pre-Columbian times evolved into prolonged and more intense contact in the seventeenth century, when the first permanent settlements were established. The trade relations between early settlers and the First Nations were instrumental in securing the former’s survival in the new land and in familiarising them with the geography of inland North America. However, even before state-sanctioned attempts at cultural assimilation and the side-effects of wars between colonial powers further reduced their numbers, infectious diseases brought over from Europe decimated thousands (Morton, 2006, 16).

Читать дальше