To sum up the general assumptions which most context-oriented approaches share, it could be concluded that this categorisation implies that every dimension of meaning is assumed to be context-derived. Therefore collocates should be regarded as meaning-creating context (syntagmatic relations). Furthermore, previous relations to other lexical items also shape the two dimensions of collocational meaning (paradigmatic relations). Here, syntagmatic relations refer to directly encountered co-occurrences, which do not necessarily need to be special or noteworthy in any way. It is rather the level of previously experienced context which makes a combination of two (or more) words significant and might hence potentially contribute to the constructional process of delexicalised or semi-delexicalised patterns. Moving away from sole introspection, more recent context-oriented approaches predominantly rely on results gained through corpus research or similar sources for extensive data collection, like large-scale surveys. In the analysis of corpora, syntagmatic relations become obvious through concordance lines, while reoccurring patterns throughout different texts and genres help with analysis of paradigmatic relations.

2.2 Significance-Oriented Approaches

While British Contextualism at first focused on the intra- and intertextual relations which collocations establish within texts, significance-oriented approaches were from the very beginning more concerned with an adequate description of a collocation’s internal features and structures. This is because, unlike British Contextualists, these approaches are predominantly linked through the same purpose: EFL-oriented lexicography. Hence, Cowie, Howarth, Mel’cuk, Hausmann, and Siepmann might not be as closely linked by their academic vitae as Firth, Halliday, and Sinclair, but as lexicographers, they are all interested in finding a way to identify suitable language material which is relevant for learners of English and the compilation of a (learner’s) dictionary. Among the pioneers in western European lexicography were Harold Palmer, A.S. Hornby, and A.P. Cowie. Towards the beginning of the twentieth century, Palmer had opened a school in Belgium and became increasingly interested in lightening students workload with the help of a restricted vocabulary; a list that contained the most important and productive words for everyday conversation. This was the start of what since then has often been referred to as the Vocabulary Control Movement . In the 1930s, authorities in Tokyo commissioned him to design a limited vocabulary list for Japanese schools. A number of well-established publications arose from this project, such as the Second Interim Report on English Collocation (Palmer 1933), the General Service List (West 1953/1983) and of course The Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English (Hornby/Gatenby/Wakefield 1948)1. From a very early stage, while working on the First Interim Report on Vocabulary Selection (Palmer 1930), Palmer and one of his young colleagues, A.S. Hornby, realised that it would not be sufficient to provide learners with a mere alphabetical word list. Therefore, they collected 3879 collocational pairs and structured them according to word-class and internal structure. The introduction of the Second Interim Report on English Collocation outlines the main objective of this project as follows:

It is not enough to suggest in a haphazard way the inclusion or exclusion of any word, word-compound, phrase, proverbial expression, etc. that may occur to us. The work must start with collecting and classifying, and this must be done on a large scale and according to an organized plan – and we have been doing on a large scale and according to an organized plan this work of collecting and classifying those things that must be collected and classified. (Palmer 1933: 1)

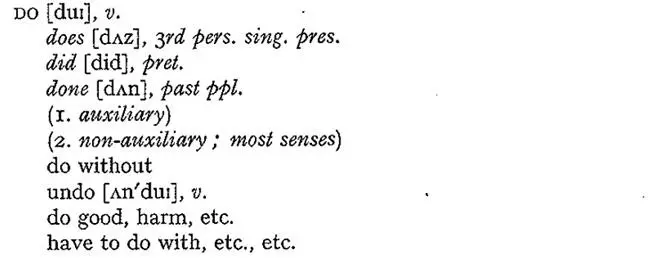

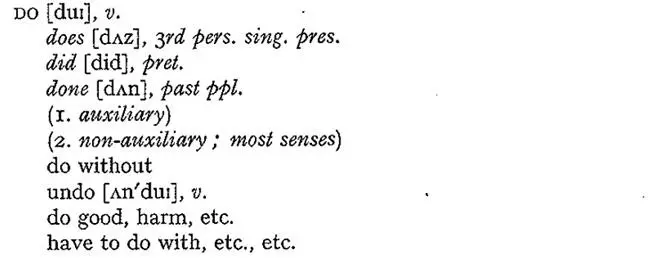

Coming back to Humpy Dumpty’s phraseological chunks: scornful tone or neither more nor less do not occur at all. Do work and make a remark, on the other hand, are both part of a rather large and heterogeneous category called “verb collocations: combinations of verbs with specific nouns” (Palmer 1933: 50). Introducing notions like (x to x N 3) or x to x N 3 , the authors tried to subdivide this group into members which take or can take an additional2 object, like make a remark and those which remain unaltered, such as do work . This is interesting since the idea of a lexically fixed word combination with a slot for potential alternation is quite similar to patterns in valency theory (Herbst/Heath/Roe/Götz 2004) or pattern grammar (Hunston/Francis 2000) and of course semi-lexical constructions like Goldberg’s argument structure constructions (Goldberg 2006: 19–44). However, since the verbs are listed in alphabetical order, this again resembles a rather long list of more or less random entries selected by proficient native speakers. Thus, in later publications, such as Thousand-Word English (1937), Palmer and Hornby included information on pronunciation, as well as morphological alterations and disambiguation for polysemous words. The latter they achieved through linking, for example, the lemma with its potential antonyms and collocations, as can be seen in the example of do (box 2.1):

Box 2.1: Entry for the lemma do from Thousand-Word English (Palmer/Hornby 1937: 43)

In general Palmer’s own selection subsumes a rather wide range of word occurrences and syntactic patterns under the term collocation (Palmer 1933: 7); nonetheless, his work has without a doubt had “a profound and enduring influence on modern EFL dictionary-making” (Cowie 1999: 52). Since then lexicographers have struggled to develop a classification for “those things that must be collected and classified” (Palmer 1933: 1) which is comprehensive and universally applicable at the same time. Consequently, Palmer’s work did not only inspire scholars like Hornby3 and Cowie4 to enhance the lexicographical description of phraseological language in general and collocations in particular, but also lay the ground for further research on collocational phenomena within modern language teaching and language acquisition research (Ellis/Simpson-Vlach/Maynard 2008; Jehle 2007; de Cock 2003; Bahns 1997; Howarth 1996)

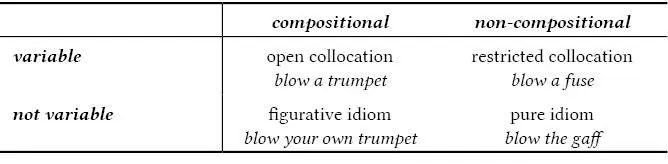

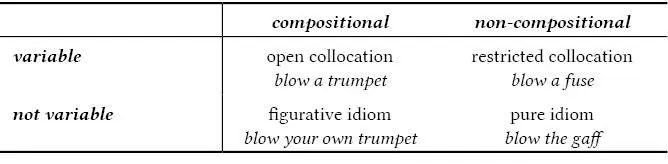

A.P. Cowie shares Palmer’s concern that a broad definition of partly fixed and opaque language could again lead to an unnecessary workload for language learners (Cowie 2012: 390). Therefore, he proposes a more clear-cut definition of the combinations within the spectrum of idioms, collocations, and free combinations. Leaving Palmer’s more formalistic approach behind, he regards compositionality and variability as the two defining criteria of composite units (table 2.3). According to this classification, the common denominator for collocations is a certain level of variability with a distinction between open and restricted collocations on the compositionality level.

Table 2.3: Categorisation of lexical word combinations according to Cowie (1983: xii-xiii) with examples from Howarth (1996:15–16)

Blow a trumpet , for example, would be regarded as an open collocation because trumpet as well as blow occur in their literal sense (compositional) and are at the same time exchangeable with other lexemes within the same paradigm like horn or play (variable). Blow a fuse , on the other hand, also shows a certain degree of variability. While, admittedly, blow is relatively fixed, top or stack could also be used to express the concept of “to get very angry” (OALD 7: blow a fuse ). In all cases, however, its meaning lies beyond the prototypical sense of the verb blow and the respective nouns. Only via a chain of metaphorical extensions, for example, “ANGER IS THE HEAT OF A FLUID IN A CONTAINER” (Lakoff 1990: 383), could one construe a link between the literal meaning of this collocation and its figurative sense. This restriction makes blow a fuse less clear and comprehensible for the learner and, therefore, needs to be part of a comprehensive learner’s dictionary. For open collocations such as blow a trumpet, no further explanation is necessary, at least from a decoding point of view.

Читать дальше

![Chade-Meng Tan - Search Inside Yourself - Increase Productivity, Creativity and Happiness [ePub edition]](/books/703803/chade-thumb.webp)