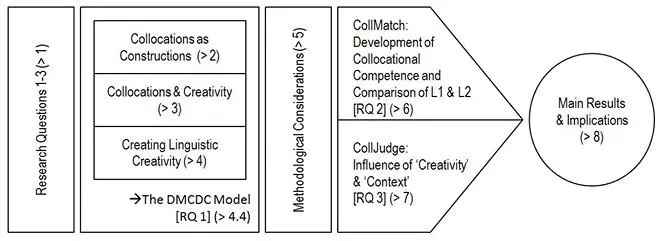

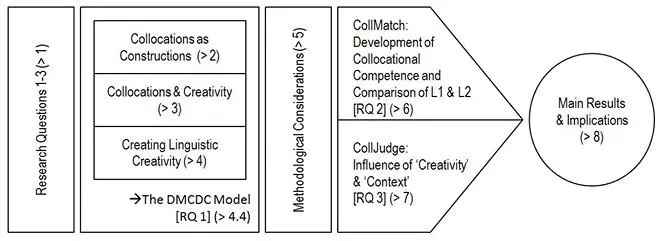

Figure 1.1: Scope of this Study

2 Collocations as Constructions

When I use a word, 'Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, 'it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.' 'The question is,' said Alice, 'whether you can make words mean so many different things.' […] 'When I make a word do a lot of work like that,' said Humpty Dumpty, 'I always pay it extra.' 'Oh!' said Alice. She was too much puzzled to make any other remark.

(Carroll 1871/2001: 224–225)1

The debate about the defining properties of collocations seems to be as old as research within the field of lexical co-occurrences itself. Partly because studies on the character and value of collocations have been conducted for various reasons and purposes; the areas of research range from a very applied EFL context (de Cock 1999; Bahns 1997; Howarth 1996; Cowie/Howarth 1995; Hausmann 1984) to lexicography (Cowie 2012; Mel’cuk 1998; Benson/Benson/Ilson 1997; Bahns 1996; Hausmann 1985) and more theoretical, general linguistic description (Coseriu 1967; Firth 1951/1964, 1957/1968). However, a duality in conception might also have developed from the fact that interest in these special cases of lexical co-occurrence arose roughly at the same time within different schools of linguistics. British Contextualism, with its most prominent representative J.R. Firth at its centre, is frequently quoted as the cradle of the modern concept of collocation (Barnbrook/Mason/Krishnamurthy 2013: 36; Bartsch 2004: 30; Lehr 1996: 7), but also within lexicography authors like Palmer (1933), Hausmann (1984) or more recently Siepmann (2005) concerned themselves with lexical co-occurrences. Their focus still tends to lie more on the properties of collocations than on their contribution to the human linguistic system. Hence today, the field of collocational research seems to be split into contextual-oriented approaches and significance-oriented approaches2 (Granger/Paquot 2008; Siepmann 2005; Herbst 1996). Based on John Sinclair’s research (Sinclair 1991, 1966; Sinclair/Jones/Daley 1970/2005) on lexical frequency, contextual-oriented approaches nowadays mostly come in the shape of corpus-based, frequency-oriented research, while representatives of the significance-oriented approach focus on typological aspects relevant for the non-native language learner, such as (non-)compositionality and variability. Today, however, both sides seem to have reached a point where they realise that they have more in common than they disagree on.

Constructions, on the other hand, are in their broadest sense defined as “form and meaning pairings” (Goldberg 2006: 3). So, with the literal translation of collocation as a certain kind of “placing together” (Palmer 1933: 7), the term as such might suggest that the phenomenon of collocation is predominantly regarded as a formal or structural one, lacking an overall meaning dimension, which would be crucial for any kind of construction (> 4). But, as the following chapters will show, even very early accounts of collocation consider not only syntagmatic relations for the constituents of a collocation, but also discuss implications for meaning which stem from a contextual or paradigmatic level within an analysis. This suggests that collocations might be more than just formal, item-specific restrictions on word co-occurrences and that there is an inherent meaning dimension, which makes it possible to regard collocations as a form of construction in a construction grammar sense.

Following this idea, this chapter will use a selection of prominent approaches towards collocations from both camps and investigate their understanding of lexical co-occurrences to shed some light on their potential constructional character. Chapters 2.1 and 2.2 will, therefore, outline the two basic views on collocation and highlight potential connections to a modern construction grammar approach. Chapter 2.3 then concludes this section, suggesting a working definition and addressing some critical issues which need to be dealt with once a study assumes cognitive features to be part of collocational phenomena.

2.1 Context-Oriented Approaches

After over 50 years of debate, the famous words “You shall know a word by the company it keeps!” (Firth 1957/1968: 179) still seem to sum up the quintessential character of any definition of collocation quite well. But Firth was not the first to acknowledge the importance of context and lexical co-occurrence for the semantic interpretation of a word. In lexicographic description, authentic context and combinatorial restrictions were already a concern for lexicographers like Samuel Johnson1 (1747/1837) and later Harold Palmer (1933). Yet, their focus was an accurate and, in the latter’s case, learner-appropriate account of the English language (> 2.2), while Firth shifted the perception of collocation from an observable phenomenon to a linguistic principle, which he considered one of the basic relations within a linguistic system, alongside grammar:

Collocations of a given word are statements of the habitual or customary places of that word in collocational order but not in any other contextual order and emphatically not in any grammatical order. The collocation of a word or a ‘piece’ is not to be regarded as mere juxtaposition, it is an order of mutual expectancy. (Firth 1957/1968:181)

This definition of collocation is deeply rooted in Firth’s firm belief in the importance of context, which he considers the main source of any kind of meaning. Unlike for example Odgen and Richards ( 101956: 10–11) and modern cognitive linguists, he claims that there is no such thing as a “hidden mental process, but chiefly […] situational relations in a context of situation […]” (Firth 1951/1964: 19). Hence, to Firth, collocation is a lexical phenomenon which operates on a syntagmatic level to create meaning through (inter-)relation and “mutual expectancy” of words. Compared to most modern definitions of collocation, this seems to be a very restricted view, but at a time when words and their meaning were nothing more than a peripheral phenomenon within linguistic research, a statement like this was a first attempt to shift the focus from a grammar-centred slot-filler perspective to a conception of language which needs both lexicon and syntax to form meaningful linguistic speech. One could even argue that Firth’s acknowledgement of meaning-building syntagmatic relations in language did in fact lay the ground for modern cognitive linguistics (> 4), since it is based on the idea that meaning arises through context, which is ultimately nothing but usage and therefore in its basic assumption quite similar to modern usage-based approaches (Bybee 2010; Goldberg 2006; Tomasello 2005). Unfortunately, Firth never gave a more detailed account of what he considers to be sufficient context for “meaning by collocation”, but it becomes apparent from his publications and a few analyses (Firth 1951/1964) that this does not simply refer to some kind of compounding:

Meaning by collocation is an abstraction at the syntagmatic level and is not directly concerned with the conceptual or idea approach to the meaning of words. One of the meanings of night is its collocability with dark , and, of dark , of course, collocation with night . (Firth 1951/1964: 196)

The example of dark night, however, seems to be somewhat misfortunate. First, because it suggests a certain spatial closeness of collocates, which, as the next example will show, is not a necessary prerequisite for the concept of “context” and “meaning by collocation”. Secondly, in this case, it is difficult to argue for “meaning by collocation”, because the co-occurrence of dark and night could also refer to real-life, extra-linguistic experience, since darkness is one of the predominant semantic components of night , even without its co-occurrence with dark (Herbst 1996: 384). Therefore, another of Firth's frequently quoted examples might be more suitable to explain the basic assumptions of this early contextualistic approach: you silly ass . Here, Firth claims that the additional meaning which arises through collocation is some kind of “personal reference” (Firth: 1951/1964: 194–195). So, when encountering a sentence like (4) one would directly conclude that the referent of ass is a person and not a donkey, because of past experiences with similar cases, such as (5) to (8)2:

Читать дальше

![Chade-Meng Tan - Search Inside Yourself - Increase Productivity, Creativity and Happiness [ePub edition]](/books/703803/chade-thumb.webp)