| (4) |

BNC A0D 1316 |

I'm on in five minutes, that old ass slowed me down. |

| (5) |

|

An ass like Bagson might easily do that. |

| (6) |

|

He is an ass. |

| (7) |

|

You silly ass. |

| (8) |

|

Don’t be an ass. |

Take another example from this chapter’s introductory quote: scornful tone . In this case, one can conclude that what the egg-shaped creature said was not very nice or polite even without necessarily being familiar with an adjective like scornful , since tone is often encountered with negatively marked premodifications such as dismissive or harsh 3.

However, these examples show that, even though Firth explicitly stresses the syntagmatic character of collocations, his conception nevertheless includes an inherent paradigmatic level through the notion of “mutual expectancy”, since any expectation is based on previous experience. Therefore, in order to know the company a word keeps, one needs to have encountered this very word in various contexts and processed it with the help of some kind of cognitive storage. Yet, whether Firth would agree with this observation or not is difficult to tell, since his description of collocations remains in a rather vague state throughout his publications (Firth 1951/1964; 1968) and Lyons (1977: 612) is certainly right when he observes: “Exactly what Firth meant by collocability is never made clear.”

Despite all criticism, Firth’s thoughts on collocation and its influence on the meaning of a lexical unit did inspire his students, John Sinclair and Michael Halliday. Based on Firth’s first sketch of these special phenomena of partly restricted co-occurrence, two approaches towards collocation have emerged: a frequency-oriented approach with corpus linguists like John Sinclair and Göran Kjelmer at its centre and a text-oriented approach, which was primarily developed by Halliday. While Sinclair’s definition of collocations as an observable phenomenon of statistical significance within a linguistic system is still the basis for collocational research today (among others Hanks 2013; Moon 2009; Bartsch 2004; Stefanowitsch/Gries 2003; Hunston/Francis 2000), Halliday’s concept of collocation as a meaning-creating phenomenon is frequently rejected as a misnomer for a special form of cohesive tie within textlinguistics (Herbst 1996: 381). However, especially in his early publications, it was Halliday who explicitly added a paradigmatic level to a contextualist perception of lexical co-occurrences. He was, therefore, the first to acknowledge an experience or usage-based dimension within lexis.

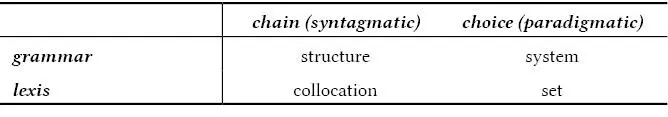

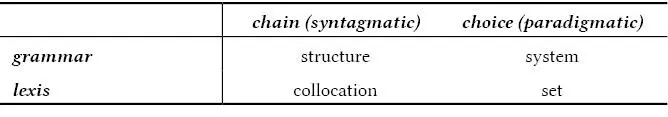

Like his approach to grammar, Halliday’s general conception of collocation is strongly influenced by Firth’s notion of the importance of context. Yet, employing a more systematic definition of basic principles within language, he tries to base the relations of lexical as well as syntactical linguistic elements on conceptually more solid ground. He introduces a two-dimensional model to illustrate the most prominent interdependencies of language (Halliday 1966: 152–153).

Table 2.1: Lexical and grammatical relations (based on Halliday 1966: 152–153)

Following de Saussure (1916/1967: 147–148) he argues for a lexico-grammatical as well as a syntagmatic-paradigmatic level of analysis and positions collocation at the intersection of syntagmatic, lexical phenomena (table 2.1). By definition, a paradigmatic level is excluded here. This would make collocation a rather broad category for all things within one string of words (= chain), but not every linear co-occurrence would count as a collocation in Halliday’s books. Again, the notion of “mutual expectancy” or “significant proximity” plays a crucial role:

First, in place of the highly abstract relation of structure, in which the value of an element depends on complex factors in no sense reducible to simple sequence, lexis seems to require the recognition merely of linear co-occurrence together with some measure of significant proximity, either a scale or at least a cut-off point. It is this syntagmatic relation which is referred to as ‘collocation’. (Halliday 1966: 152)

Coming back to the example of Humpty Dumpty, what Halliday would presumably regard as collocations are expressions like neither more nor less , do work or make a remark , not so much because of their reoccurring character throughout a text or discourse, as would be the case for Firth’s concept of “meaning by collocation”, but rather because of their restricted nature. He therefore stresses that “[i]n lexical analysis it is the lexical restriction which is under focus: the extent to which an item is specified by its collocational environment.” (Halliday 1966: 156). Neither more nor less , for example, could not, or at most fairly rarely, be expressed as neither less nor more 4, do work is much more usual than make work and vice versa, and one makes a remark instead of does a remark . The adjective scornful in a combination like scornful tone, on the other hand, might be mutually expected in terms of meaning or, to be more precise, the likelihood of a negatively marked adjective to occur with the nominal use of tone , but it is not an item which shows “significant proximity” with the noun, since the same concept could be equally well expressed with condescending or sarcastic 5. To analyse likely candidates for lexical co-occurrence, Halliday establishes the concept of lexical sets , which is of course closely related to collocation , since its members are selected based on “the similarity of their collocational restriction” (Halliday 1966: 156) Later he continues: “If we say that the criterion for the assignment of items to sets is collocational, this means to say that items showing a certain degree of likeness in their collocational patterning are assigned to the same set.” (Halliday 1966: 158). The value of this distinction between paradigmatic and syntagmatic level is that it clearly shows two principles which apply to any word co-occurrence with an intuitively – at least for native speakers of English – close relationship: the fact that the constituents cannot be substituted by any random word with roughly the same semantic concept ( collocation ) and a certain underlying meaning value which words with similar collocation share ( lexical set ). This is strikingly similar to the principles of cognitive linguistics in general and construction grammar in particular, since more abstract constructions, like argument structure constructions (Goldberg 2006: 19–44), are at their heart very much like Halliday’s collocations and lexical sets. They open up slots on a paradigmatic level, which influence word choice based on certain meaning restrictions, not unlike collocations, so ultimately this leads directly to a notion of collocations as constructions (> 2.3; 4). Admittedly, in later publications like his 1976 co-authored book on Cohesion in English (Halliday/Hasan 1976), Halliday focuses more strongly on Firth’s original concept of “meaning by collocation” and draws away from his general thoughts on the structure of lexical relations within language.

The Collins Birmingham University International Language Database (COBUILD), the result of cooperation between the University of Birmingham and Collins Publishers, started in 1980. The aim of this project was to build a large corpus of contemporary text (100 million words) in order to analyse the lexical and grammatical foundations of the English language on a more systematic basis. The pilot project, the OSTI Report (Sinclair/Jones/Daley 1970/2005), had already yielded some interesting insights into the pervasive nature of collocational phenomena, so with this follow-up project Sinclair and colleagues concerned themselves once more with a detailed, corpus-driven6 analysis of lexical items. The result was, as intended, a comprehensive corpus-based dictionary of the English language, the Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary (COBUILD 1, Sinclair 1987a), but the OSTI report and the conception of the COBUILD 1 also influenced research on collocations in general. Until then, analysis of collocations was based on a rather random sampling of examples and seemed to be somewhat eclectic at times. So, following Firth’s thoughts on the co-occurrence of words, Sinclair took further steps towards the operationalization of the concept of collocation. In order to do so, he labelled its components node , for the lexical item under investigation, and collocate , for “items in the environment” of the node which co-occur in a text or sentence within a certain distance, the span 7 (Sinclair 1966: 415). Leaving introspection behind, all these elements can then be retrieved and correlated with the help of a corpus, which could be regarded as a kind of replica of adult human linguistic experience. In principle, this leads to a very simplified basic assumption: the more frequent, the more important. Unsurprisingly, the notion of frequency is also at the centre of Sinclair’s concept of collocation :

Читать дальше

![Chade-Meng Tan - Search Inside Yourself - Increase Productivity, Creativity and Happiness [ePub edition]](/books/703803/chade-thumb.webp)