But in many cases, the concept of (non-)compositionality at this stage is not very clear and precise. Blow a fuse , for example, could also be used in a more literal sense of ‘causing a fuse to melt’. Here the most opaque element is blow . This might suggest more compositionality and, therefore, would put blow a fuse under the category of open collocation, yet there are not many other items which can be destroyed through “blowing”, like gasket or cover , which then again would yield an analysis as a figurative idiom. Thus, as for statistically significant collocations, the question arises whether the limited variability of blow a fuse is due to linguistic restriction or rather because it belongs to a special vocabulary on a pragmatic basis which is restricted to the fields of electricity and insulation (Herbst 1996: 386–389; > 2.1). Furthermore, it is also interesting to note that the use of blow a fuse in its “enragement” sense is probably a metaphorical extension of its use to describe the destruction of a piece of wire or rubber. This concept of a mutual influence of meanings mirrors to a certain degree what construction grammar has termed inheritance relations within an inventory of constructions (Fischer/Stefanowitsch 2006: 4–5; Fried/Östmann 2004: 23–14), which today is regarded as a basic principle within language acquisition by most proponents of these linguistic approaches.

To refine his typology of composite units, Cowie, in a later publication with Peter Howarth, adds two more features to his characterisation of collocations and idioms (Cowie/Howarth 1995: 82), namely that phraseological units, independent from their variability and semantic opaqueness, are institutionalised and memorised. They conclude that “[i]t is best to think of a collocation as a familiar (or institutionalized), stored (or memorized) word-combination with limited and arbitrary variation.” (Cowie/Howarth 1995: 82). Similar to usage-based theories, this stresses the fact that collocations need to be repeatedly encountered and learned, an observation which has also been made by Pawley and Syder (1983):

Indeed, we believe that memorized sentences and phrases are the normal building blocks of fluent spoken discourse, and at the same time, that they provide models for the creation of many (partly) new sequences which are memorable and in their turn enter the stock of familiar usages. (Pawley/Syder 1983: 208)

Moving away from a clear categorisation based on semantic opaqueness in favour of the extent of limited choice and the number of choices a language user has within a collocation, this distinction is in fact very similar to Sinclair's notion of casual and statistically significant collocations. Yet, the source of this significance is, of course, different from a frequency-oriented approach, since compositionality, in Cowie’s terminology, still lies in the eye of the (native speaker) beholder. With this definition, lexicographers and EFL teachers can of course fairly easily account for a certain feel of collocability, which might not be analysed as statistically significant but nevertheless seems to be an important contribution to a language learner’s lexicon. On the other hand, introspection and personal judgment still play a fairly important role in this definition, which makes it difficult to justify any classification on more general grounds.

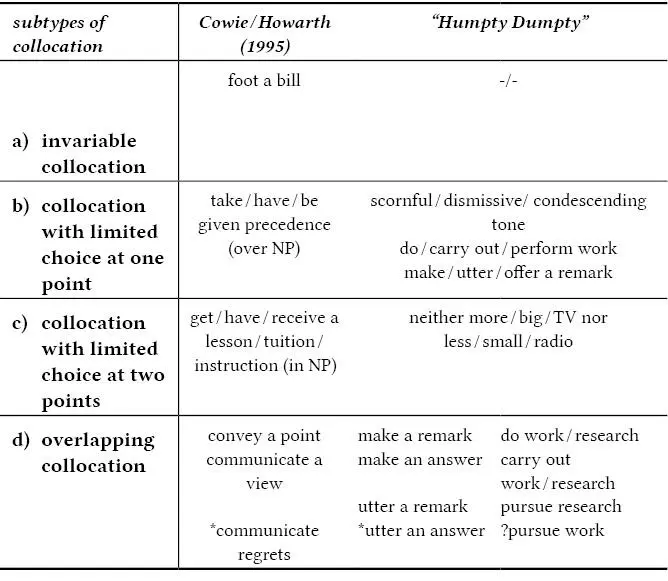

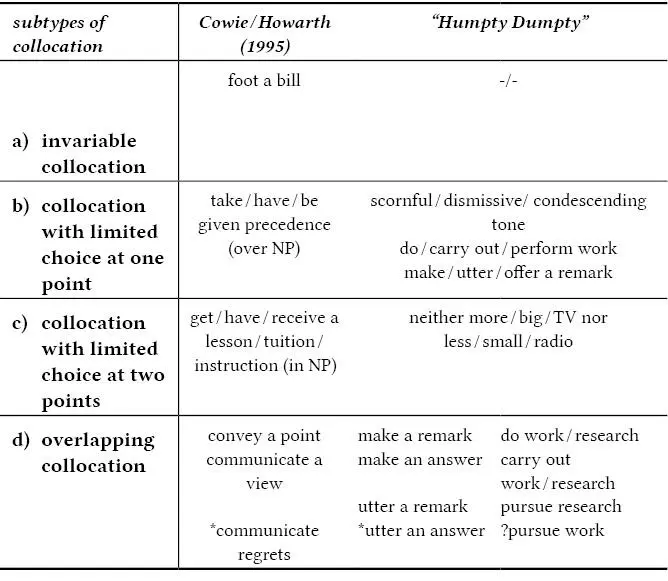

Table 2.4: Categorisation of open collocations (Cowie/Howarth 1995: 83)

Again, Humpty Dumpty and his phraseology shall be used to exemplify this. In their study Cowie and Howarth explicitly focus on open collocation and claim that these phraseological units are most fitting for the investigation of proficiency levels amongst native and non-native speakers of English. They introduce four subcategories for collocation (Cowie/Howarth 1995: 83). At first glance, the attempt to assign scornful tone , do work , make a remark and neither more nor less to these categories seems to work quite well (table 2.4), until one considers closely related collocations, like make an answer and utter a remark . Here, the limited interchangeability, for example with utter an answer or also pursue work , would then put make a remark and do work into category d) and water down the precision of this classification. In fact, this applies to most members of b) and c), which is probably due to the fact that, whenever one allows for variability, a certain degree of overlap is one of its potential consequences. Thus, this typology seems to demonstrate the variability-side of collocations quite well and also accounts for more than one slot within a collocation. But it struggles to provide a clear definition or explanation for restrictions, which then makes it seem rather arbitrary and vague. Cowie and Howarth’s subcategories are nevertheless remarkable, since, even though ”invariable collocations” seem to resemble in fact what used to be called idioms, Cowie and Howarth’s typology now looks strikingly similar to semi-lexical constructions, with one or more open slots and fixed lexical items in between (> 4).

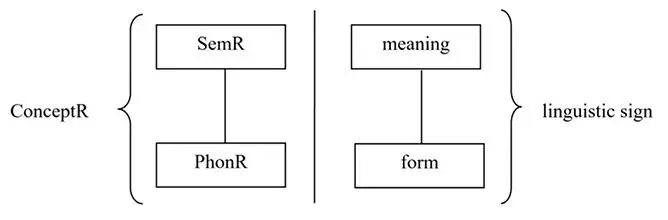

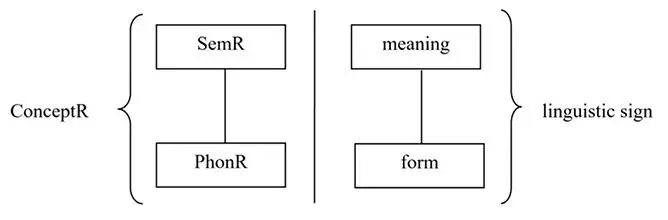

At the same time as Cowie developed his first framework on collocations, Russian linguists like Igor Mel’čuk studied collocational phenomena in a more formalistic way. Here the focus does not lie on the language learner him/herself. Mel’čuk sees his approach rather as a comprehensive and structured way to describe phraseological phenomena in order to obtain thoroughly processed data for the compilation of a dictionary or computational linguistic purposes. Therefore, the native speaker’s viewpoint stands at the centre of his conception of text production (Mel’čuk 1995: 25–24). In general, Mel’čuk assumes that whenever a (native) speaker wants to express a certain concept (ConceptR), s/he needs a phonetic representation (PhonR) from a language (L) in order to realize a semantic representation (SemR). Lexical functions (LF) are then part of a comprehensive inventory of semantic representation (SemR) (figure 2.1); a conception which in fact looks rather similar to de Saussure’s (1916/1967: 76–79) notion of the linguistic sign and therefore also to any constructions.

Figure 2.1: Mel’čuk’s (1989, 1995) process of text production compared to de Saussure’s (1916/1967: 76–79) linguistic sign

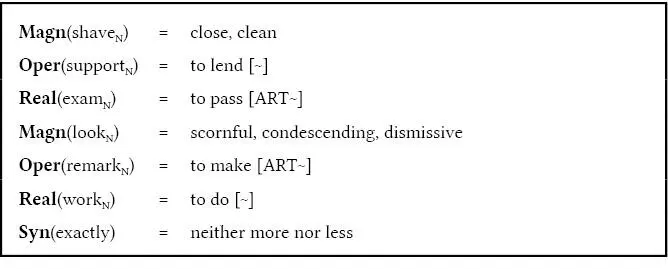

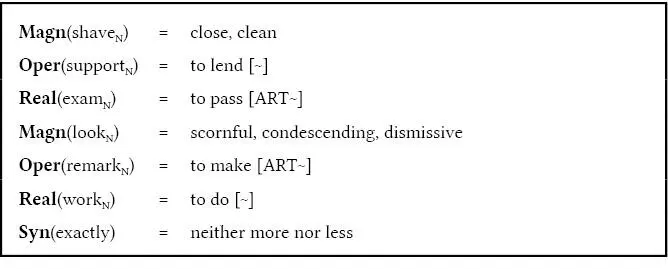

Based on this concept, Mel’čuk’s idea was to describe lexical units like set phrases and collocations on the basis of a general underlying meaning (Mel’čuk 1995: 186). Since collocations, as Mel’čuk claims, “make up the lion’s share or the phraseme inventory […]” (Mel’čuk 1998: 24) and almost all collocations are covered by syntagmatic lexical functions, it seems useful to have a closer look at some examples of lexical functions. Box 2.2 shows the respective LFs for the set phrases cleanly shaven , lend support or pass an exam , as well as scornful look , make a remark, do work and neither more nor less :

Box 2.2: Lexical functions of phraseological phenomena according to Mel’čuk (1995: 186)

Читать дальше

![Chade-Meng Tan - Search Inside Yourself - Increase Productivity, Creativity and Happiness [ePub edition]](/books/703803/chade-thumb.webp)