At this point we might have to reassess our entire framing of our own agency in the fraught political area of global environmental politics—and of global politics tout court , because there is nothing, in fact, that escapes the gambit of the politics of global warming. Perhaps, in rethinking the time of ‘temps’ and ‘tiempo’, we might also rethink the relationships between temporality, temporariness and our own actantial contributions to a threatened world. For, if we are to rethink politics in a world where glaciers are ‘both animate (endowed with life) and animating (giving life to) landscapes they inhabit’ (Cruikshank 2005: 3) we need to rethink our notions of agency. This ‘animated’ and ‘animist’ approach to the world does not merely attribute agency to entities habitually thought of an inert or passive (the agency of the glacier as merely an immensely slow manifestation of the downward pull of gravity), but rather, sees all entities in the world as co-actants: endowed with devolved agency by their neighbouring actants with whom they exist in an ineluctable meshwork of interaction. Life, or ‘the living’, Simondon (1964: 260) claims, ‘lives at the limit of itself, on its limit’ (qtd in Deleuze 1990: 103). It does so in a constant encounter, at the edge, with Others who thereby endow it with their life. Animist agency in this reading is not ‘internal’ to the hitherto inert or lifeless object, but, true to the etymology, like a wind, blows through each entity, transversally, animating them from outside (Ingold 2011: 29). Animist agency is not a stable attribute of an entity, but rather, a temporary, tempestuously ‘windy’, fluctuating derivative. Agency can never exist without a hyphen, and it can never exist except in a provisional and contingent temporal mode. Agency is never a given, but must be constantly renegotiated with the co-agents that co-determine what agency might be, and where it might lead.

Agency, then, by definition, is related to the new. It does not imply the reproduction of self by the imposition of will in an intentional vector beyond and in front of oneself, as Merleau-Ponty’s (1945) phenomelogical spatiality implies. This merely translates into the colonial vector of conquest celebrated by Carter’s Road to Botany Bay (1987) in the colonial act of travelling-as-naming. Rather, this mode of agency implies the production of the new at every turn, because every instance of agency involves an engagement with an other. Such engagements cannot be predicted in advance. Their temporal mode is that of the contingent, the exploratory, the tentative—even if they are an engagement with the actantial temporality of a mountain.

Thinking agency anew, as the new, in the light of animist interactions, may be a surprising and unexpected key to political renewal. Slavoj Žižek (2016: 108) laments the utter untimeliness of democratic politics today, citing the hopeless fate of democratic governments from Greece to Venezuela as examples of a politics that is completely against the flow of history. Such opposition to history, he suggests, is in fact a freedom from the shackles of history, a freedom to act, and to produce the new out of the sheer dynamics of desperation. Mark Terkessidis (2017) similarly demands a complete renewal of the politics of migration, given the utter lack of future perspectives or vision displayed by the political class as they react to the ineluctable refugee crises that characterize our times. Only the work of imagination, he suggests, will produce new options under these circumstances.

For such a ‘new’ to emerge, we must embrace a version of co-agency that welcomes all actants into the coalition of the democratic, nonhuman as well as human. The times of shared democratic agency may sometimes be tempestive, seasonal, but we must not mistake them for some putatively true temporality of the agency of mountains. Stolid and unmoving as they may seem, the agency of mountains may also be tempestuous and unpredictable—within a time- and speed-frame to which we are only just beginning to accustom ourselves.

RWP

‘In that the world’s contracted thus’

All is in each of us, and we all deserve this acknowledgement, but as the sun shines across the planet it takes us collectively as well as individually. And human-induced climate changes alter the conditions under which the earth receives the sun’s bounty, shifting the range of sustainability through which life was nurtured.

Subjectivity and damage to the biosphere are as intimately linked as the inevitable vast movements of people are to human conflict. Cause and effect are the poles we struggle between and deny, remaking our own images to convey to a world we hope is eager to see who we are, the very essence of our being. Modernity of the now is tied deeply to the way we materialise the soul through consumerism, making our interiority visible, and it seems consciously or unconsciously, to many, a price worth paying. A price. Worth paying. Breaking it up, the absurdity increases as syntax is designed to retain a status quo of reason, to ensure information is conveyed in an absorbable, comparative, and recognisable way, however different we are as individuals, or cultural collectives.

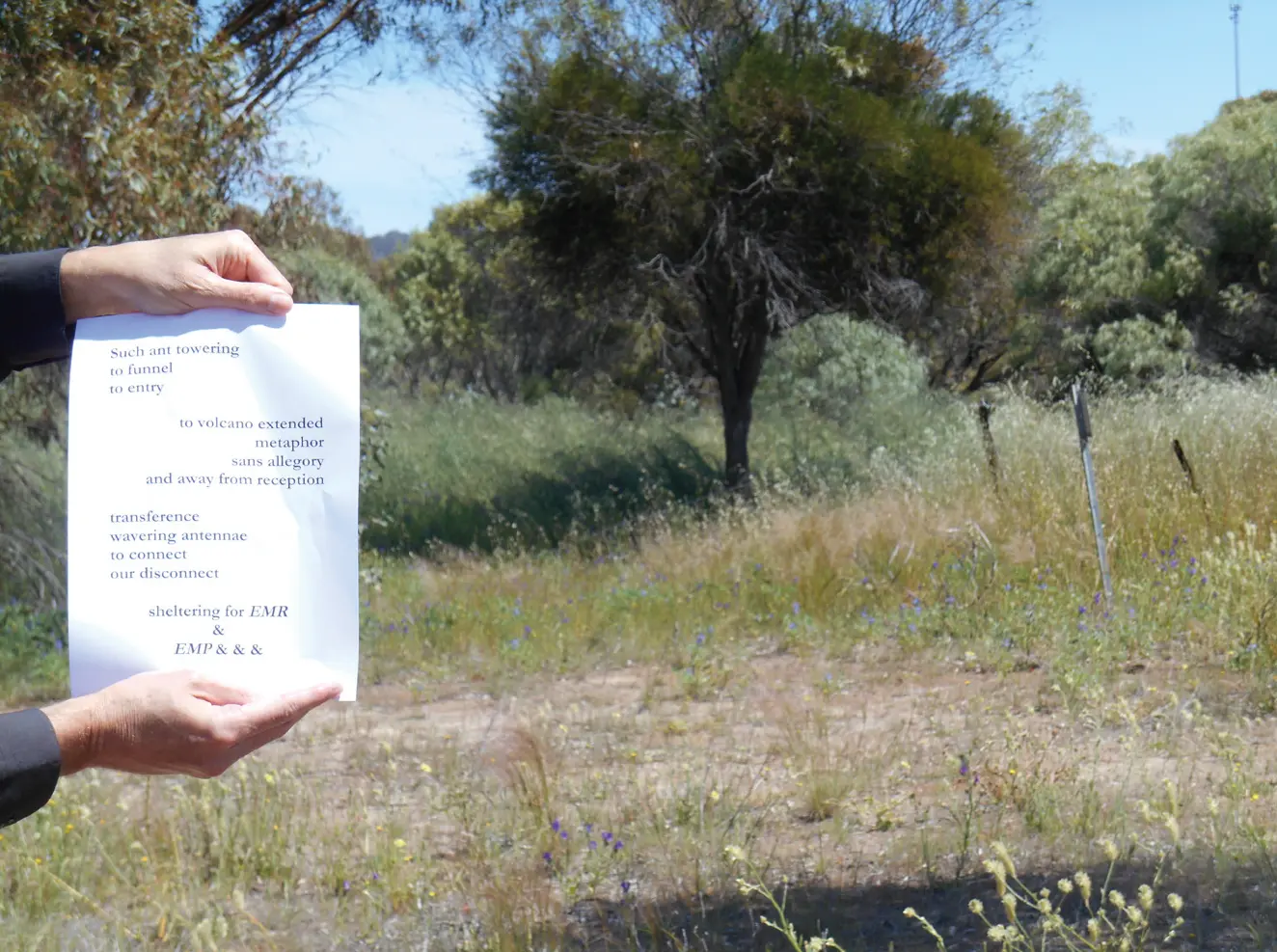

But when language is broken free of its patterns, it bothers and disrupts, and the accepted forms of social media do all they can to pull these disruptions back into line. While we resist as poets, reworking language into new possibilities, we also subscribe to a status quo that has contracted the world to the self, to materialistic gain, leisure and pleasure.

In what follows I proffer specific instances of ecological protest, and a more general shared action against consumerism that I believe can dislodge the ruling elites that disempower citizens. As an anarchist vegan pacifist (and all these qualifications of each ethical and political ‘component’ are necessary), I believe that ‘citizenship’ denotes the rights to inclusive participation (through consensus) of all bodies in a community, should an individual wish to participate. I believe in small communities that self-govern outside configurations of centralised power, and that make decisions for a social good, with each other’s welfare as well as that of the self kept in mind in all such decision-making.

The brutality of Theresa May’s ‘to be a citizen of the world is to be a citizen of nowhere’ is emphasized when expressed within such a belief system (or dynamic), as the ‘nowhere’ is very much the small non-flag-waving community. Through what I term ‘international regionalism’—respecting regional integrity while fostering international lines of communication in order to prevent conflict and promote understanding between different communities around the world—citizens embrace cultural diversity, pluralism of life choices, and tolerance of difference.

In other words, as citizens of small communities outside centralised power constructs, we are also citizens of the international, of the world. That citizenship is open, non-prescriptive, flexible in definition, and tolerant. We are citizens only insofar as we are individuals with obligations to other individuals, and these citizens (flagless, nationless) are part of all other small communities, as much as part of the one we make decisions in. The ‘social media revolution’ has created faux and facsimile communities that can activate but ultimately detract from a cause because of the costs at which they come. The centralised, controlling power in this context is the corporate machine behind software, and even if ‘open’ software, certainly behind the manufacture of the hardware. But social media is about social policing while fitting a consumer model of empowering the companies who own the softwares. Twitter benefits greatly from Trump’s threats of nuclear annhilation via its service—it’s ‘pure’ apocalyptic business. I search for liberty from these constraints, and to decrease the ironies of any protest activity through this.

Читать дальше