Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

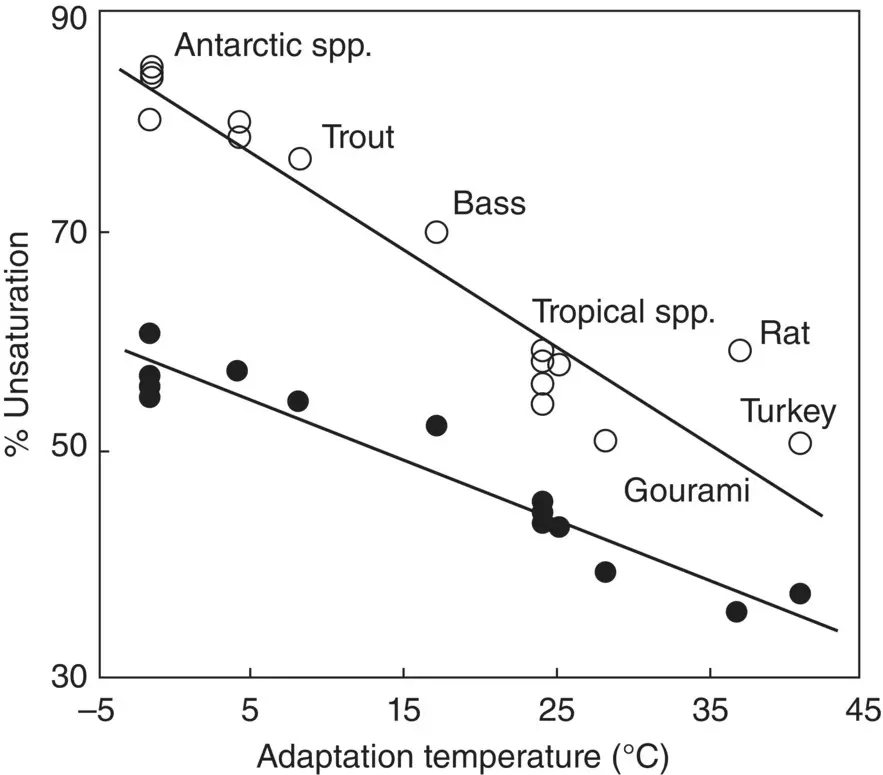

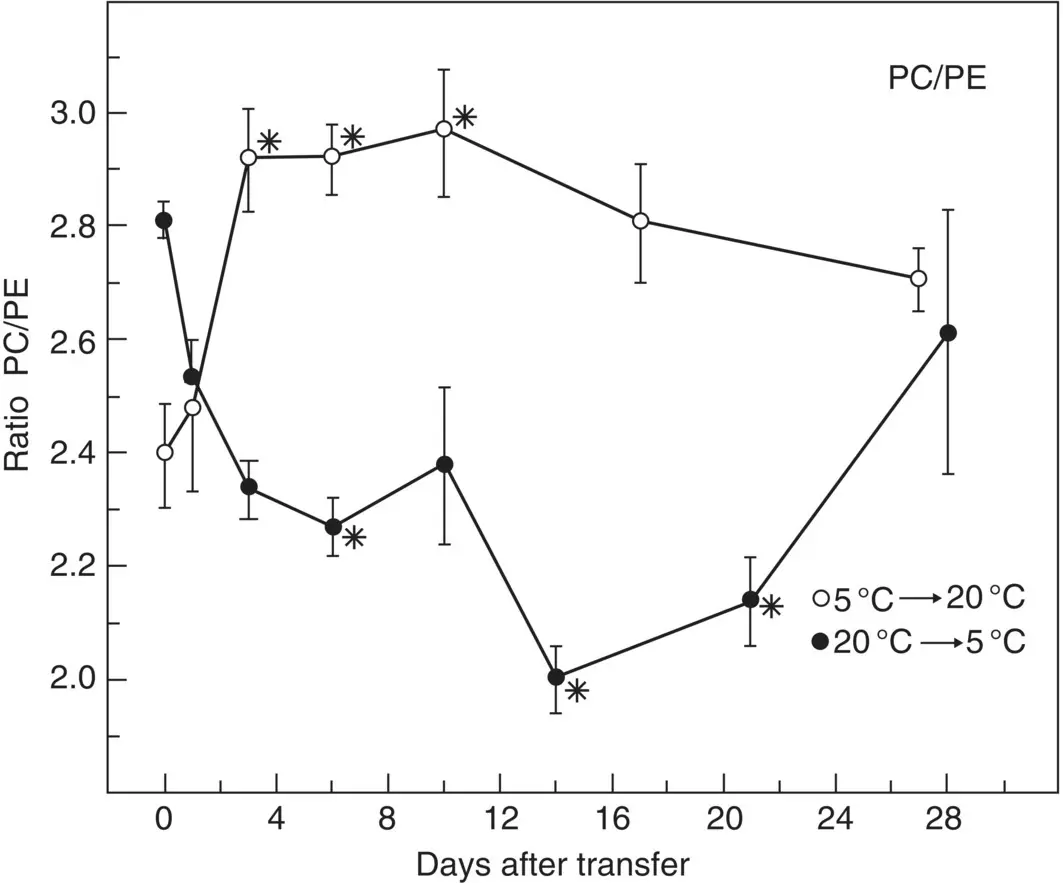

It is most important to appreciate that not only do species’ membrane lipids vary greatly in character with the changes in habitat temperature typical of different zoogeographic regions, but considerable acclimation to temperature change by membrane lipids can also occur within a period of days to weeks. Such short‐term change can be considered part of the overall acclimation process that allows a species to adjust its upper and lower lethal limits (see Figure 2.2a, the tolerance polygon).

Table 2.2 Chemical formulas and melting points for a selection of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.

| Carbon atoms | Common name | Empirical formula | Chemical structure | Melting point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated fatty acids | ||||

| 3 | Propionic acid | C 3H 6O 2 | CH 3CH 2COOH | −22 |

| 12 | Lauric acid | C 12H 24O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 10COOH | 44 |

| 14 | Myristic acid | C 14H 25O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 12COOH | 54 |

| 16 | Palmitic acid | C 16H 32O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 14COOH | 63 |

| 18 | Stearic acid | C 18H 36O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 16COOH | 70 |

| 20 | Arachidic acid | C 20H 40O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 18COOH | 75 |

| Unsaturated fatty acids | ||||

| 16 | Palmitoleic acid | C 16H 30O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 5CH=CH(CH 2) 7COOH | −0.5 |

| 18 | Oleic acid | C 18H 34O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 7CH=CH(CH 2) 7COOH | 13 |

| 18 | Elaidic acid | C 18H 34O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 7CH=CH(CH 2) 7COOH | 13 |

| 18 | Linoleic acid | C 18H 32O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 4CH=CHCH 2CH=CH(CH 2) 7COOH | −5 |

| 18 | Linolenic acid | C 18H 30O 2 | CH 3CH 2CH=CHCH 2CH=CHCH 2CH=CH(CH 2) 7COOH | −10 |

| 20 | Arachidonic acid | C 20H 32O 2 | CH 3(CH 2) 4CH=CHCH 2CH=CHCH 2CH=CHCH 2CH=CH(CH 2) 3COOH | −50 |

Figure 2.15 The relationship between adaptation temperature and percentage of unsaturated acyl chains in synaptosomal phospholipids of differently adapted vertebrates. Each symbol represents a different species. Open symbols denote phosphatidylethanolamine; filled symbols denote phosphatidylcholine.

Source: Hochachka and Somero (2002), figure 7.27 (p. 372). Reproduced with the permission of Oxford University Press.

Figure 2.16 Temperature acclimation and phospholipid class. Time course of change in the ratio of phosphatidyl choline (PC) and phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE) in gill cell membranes of rainbow trout acclimating to the indicated temperatures. *indicates a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) compared to the day zero mean.

Source: Hazel and Carpenter (1985), figure 4 (p. 599). Reproduced with the permission of Springer.

Pressure

Even though pressure is the most predictable variable in the ocean, increasing by 1 atm with every 10 m increase in depth, pressure is probably the variable most difficult to intuitively understand. Ocean pressure evokes thoughts of dark and forbidding depths, of submarine movies in which the captain and heroic crew must take their craft to depths far greater than she was built to withstand, to there lie on the bottom, evade the enemy, and hope to survive. The great pressure causes the sub to creak and groan, bolts to pop like bullets out of the hull, and leaks to sprout before the ordeal can be successfully ended. However, World War II submarines could not get very deep at all, <300 m, and even modern nuclear subs do not get out of the mesopelagic zone (200–1000 m). Our view on pressure from those movies is one where pressure is acting on gas‐filled spaces. A submarine is quite a large gas‐filled space and must be immensely strong to withstand even the modest pressure of a dive to 100 m: 11 atm, 162 psi, or 11 143 kPa. In point of fact, most of the species that live under pressure do not have gas‐filled spaces, and thus the effects of pressure are far more subtle, especially in the upper 1000 m where much of the ocean’s pelagic biomass resides. In our mind’s eye though, the pressure associated with even the average depth of the ocean must be a formidable challenge to life.

Pressure at the deepest point (10 916 m) in the ocean, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench near the Philippines, is 16 046 psi (1.11 × 10 5kPa). Pressure at the average depth of the ocean of 3800 m (Sverdrup et al. 1942) is 5586 psi (3.85 × 10 4kPa). Those are big numbers and are part of the reason we have always held pressure in such high regard as an operator influencing life in the ocean. In fact, respect for pressure has colored some of the history of man’s exploration of the sea.

In the 1840s, an eminent British scientist by the name of Edward Forbes was conducting research on the bottom fauna in the coastal waters of the British Isles using an oysterman’s dredge. Depths were 600 feet (183 m) and less, and he found the fauna varied and abundant. His reputation as an ocean scientist earned him an invitation to journey to the Mediterranean to do some similar dredging. He found a very sparse bottom fauna in the Mediterranean, but the depths at which he was sampling, 1400 feet (428 m), were about twice those he had sampled off the coast of Great Britain. He assumed that the depth difference between the two regions was responsible for the change in the abundance of the bottom fauna. He decided that if the trend in declining abundance with depth continued as observed, in short order, the bottom fauna would disappear altogether. Based on his results, he declared that below a depth of 1800 feet (550 m), no life would exist and he termed those depths the “azoic zone,” the zone without life.

As time went on and exploration of the ocean continued, animals were recovered from greater and greater depths, but rather than accepting the possibility that life existed at the ocean’s greatest depths, the azoic zone just kept getting pushed deeper and deeper. In 1860 just prior to the voyage of the Challenger, the most famous oceanic expedition of all time, a submarine telegraph cable was brought to the surface for repair from a depth of 2000 m in the Mediterranean. The cable was covered with encrusting fauna, animals like barnacles and corals that build calcareous structures. Because those fauna would not have had time to create their structures on the cable during its rapid journey to the surface, the azoic theory was pretty well laid to rest at that point. The theory was further discredited by the discoveries of the Challenger over the next 5 years. Yet, there was still some doubt that life could exist at the very deepest points in the ocean, like the Challenger deep. The challenge to life caused by pressure was at least partially responsible for those doubts, along with the cold, the dark, and the distance from the sun and plant life.

The final demise of the Azoic Theory came in 1960 with the voyage of the submersible Trieste to the deepest point in the ocean. It was one of the great moments in the history of man when Jacques Piccard, son of Auguste Piccard, the submersible’s designer, and Lt. Don Walsh of the US Navy descended to the deepest point in the ocean, the Challenger Deep in the southern part of the Mariana Trench. The onboard instrumentation recorded a depth of 11 521 m, which was later revised to 10 916 m. Measurements since then have revised the estimate both up (11 034 m) and down (10 896 m) using different instrumentation, but they are all very close to the original estimate. While at depth, Piccard and Walsh observed swimming shrimps, thus showing that life can exist at the deepest point in the ocean.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.