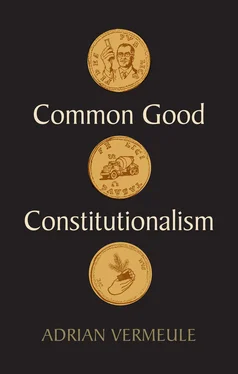

Determination – Of the Constitution and Within the Constitution

In the classical tradition, regnative prudence is closely linked to the concept of determination – the process of giving content to a general principle drawn from a higher source of law, making it concrete in application to particular local circumstances or problems. I will explain this crucial concept in detail in Chapter 1. Briefly, the need for determination arises when principles of justice are general and thus do not specifically dictate particular legal rules, or when those principles seem to conflict and must be mutually accommodated or balanced. Those general principles must be given further determinate content by positive civil lawmaking. There are typically multiple ways to determine the principles while remaining within the boundaries of the basic charge to act to promote the common good – the basis of public authority. By analogy, an architect who is given a general commission to build a hospital for a city possesses a kind of structured discretion. The purpose or end of the commission shapes and constrains the architect’s choices while not fully determining them; a good hospital may take a number of forms, although there are some forms it cannot take.

So too at the level of the whole constitutional order. The common good in its capacity as the fundamental end of temporal government shapes and constrains, but does not fully determine, the nature of institutions and the allocation of lawmaking authority between and among them in any given polity. Such matters are left for specification that gives concrete content to the operative, small-c constitution (which is not necessarily the same as the formal written Constitution even in polities that have the latter). Call this determination of the constitution.

This agnosticism at the level of institutions, in turn, has two aspects: agnosticism about institutional design, and about the allocation among institutions of authority to interpret the constitutional scheme. Parliamentary and presidential systems, constitutional monarchies and republics, all these and more can in principle be ordered to the common good. Likewise, the common good does not, by itself, entail any particular scheme of (for example) judicial review of constitutional questions, or even any such scheme at all. The common good takes no stand, a priori , on the well-known debate over political constitutionalism versus legal constitutionalism, 21so long as the polity is ordered to the good of the community through rational principles of legality. 22

This broad agnosticism does not mean that there are no boundaries whatsoever; it just means that the boundaries are set by the nature of law itself, as an ordination of reason to the common good. Certain institutional arrangements, mostly science-fictional and horrific, will be ruled out even if no one set of arrangements is uniquely specified. But they will be ruled out because they are arbitrary and unreasoned, and thus do not participate in the nature of law, not because the common good directly commands particular institutional forms. Likewise, strictly aggregative-utilitarian arrangements will be ruled out by the non-aggregative nature of the common good, an example being a substantial class of invisible-hand arrangements justified as an indirect way of maximizing aggregate utility. 23But the ruling out of certain arrangements leaves a wide scope for choice that adapts institutional forms to local circumstances.

So far I have been talking about determination of the constitution. At another level, there is also determination within or under the constitution. Particular sets of institutions (among which authority has been allocated) give further specification to general constitutional principles of the common good, such as principles of solidarity and subsidiarity and others to be discussed here. Indeed, the process of determination is iterative and continues to ever-more detailed levels, as we will see. The legislature and executive, for example, may agree on a general statute giving some specification to a general legal principle, and in turn delegate to administrative agencies the authority to determine the general provisions of the statute. The agency may do so by a binding regulation, which may then require further interpretation, and so on.

General and Particular Claims

An important corollary is that one has to distinguish (1) general claims about constitutionalism ordered to the common good from (2) specific constructive interpretations of a given constitutional order that aim to put that order, as it develops over time, in its best light. I have called the former the general part of this book, the latter its particular part. I presuppose here, incorporating previous work by reference, a particular constructive interpretation that fits-and-justifies our own developing constitutional order. In that interpretation, the American small-c constitutional order has come to feature broad deference to legislatures on social and economic legislation and broad delegations from legislatures to the executive. In operation, moreover, lawmaking is effectively centered mainly on executive government, divided in complicated ways between the presidency and the administrative agencies (including both executive agencies and independent agencies). The executive and administrative state can and does act according to the rule of law, constituted in important part by principles of regularity in lawmaking that I will discuss in later chapters. Indeed, by acting through reasoned law, our executive-centered order can be ordered to the common good.

That particular interpretation of our own constitutional order, however, is separable from the general claims about the nature and principles of constitutionalism also offered here. Agreement with the general part does not necessarily entail agreement with the particular part. One may subscribe to the general framework of common good constitutional interpretation without subscribing to the full, particular interpretation of the path of American public law that I have laid out. The failure of some commentators to distinguish general claims about the nature of constitutionalism from specific claims about the determination of the American constitutional order has produced serious confusion, and one of my aims here is to clear that up.

Courts and the Common Good

Throughout the book, I emphasize that courts need not be the institutions charged with directly identifying or specifying the common good. A division of institutional roles can, under particular circumstances, itself conduce to the common good. It is not written in the nature of law that courts must decide all legal or constitutional questions. The precise allocation of law-interpreting power between courts and other public bodies is itself a question for determination at the constitutional level.

In America, the classical tradition held that so long as determinations are made within the jurisdictional competence of public bodies, for legitimate ends, and on rational grounds, they are a matter for the public authority, not the courts. A strong legal principle of deference by courts to the determinations of legislatures was part and parcel of our law from the beginning. One of my particular claims is that our small-c constitutional order developed over time to extend this principle to the institutional presidency and administrative tribunals. Today our constitution supports the legitimacy of broad delegations to the executive, 24shaped and constrained by principles of legality that ensure that the executive acts rationally in ways ordered to the common good. 25Determination is plausibly the remote ancestor of deference in all sorts of forms that are familiar in the administrative state, such as Chevron deference 26to administrative agencies.

Читать дальше