John O'Brien - Earth Materials

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John O'Brien - Earth Materials» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth Materials

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth Materials: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth Materials»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth Materials,

Earth Materials,

Earth Materials — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth Materials», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

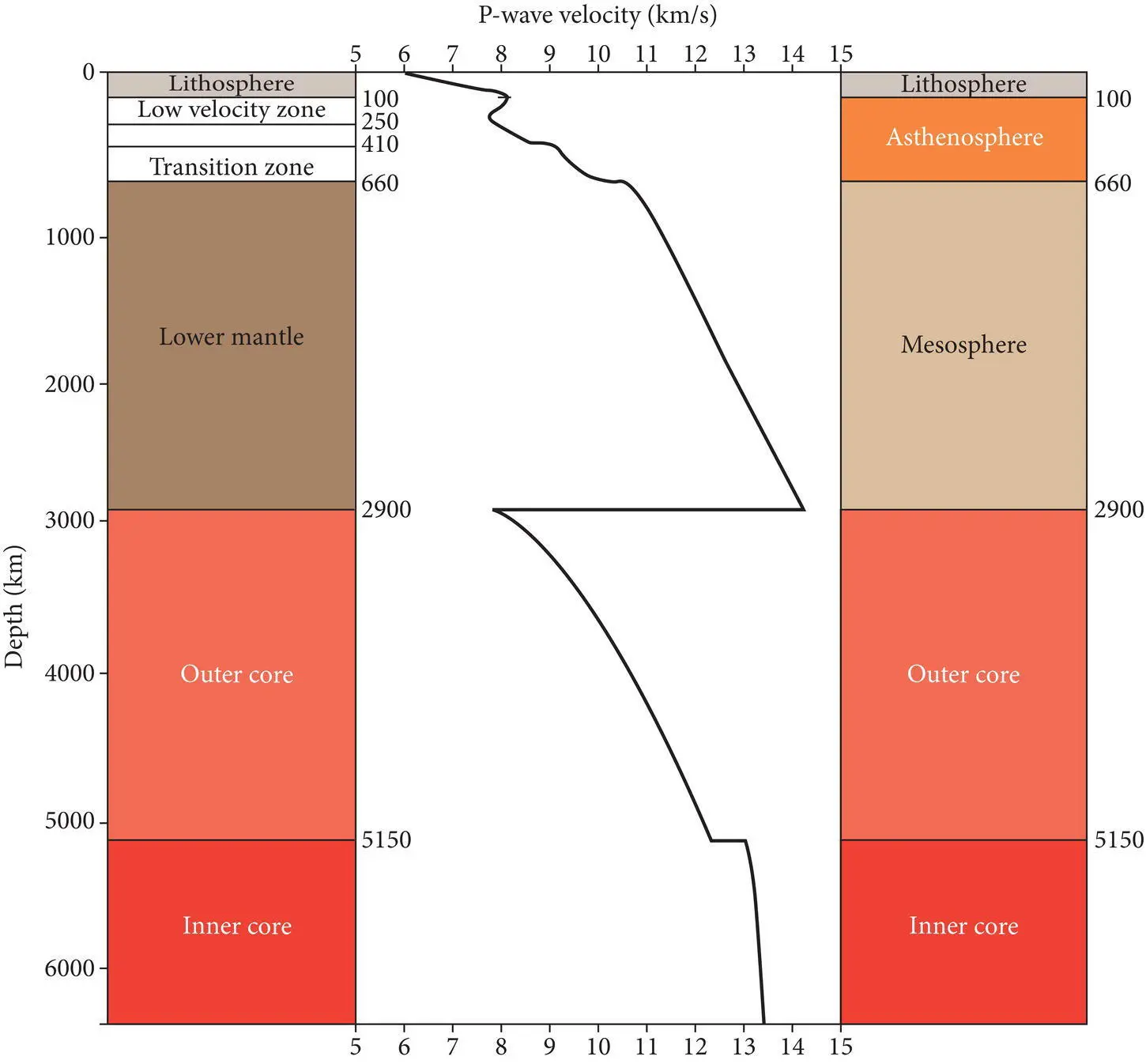

The mantleis thick (~2900 km) relative to the radius of Earth (~6370 km) and constitutes ~83% of Earth's total volume. The mantle is distinguished from the crust by being very rich in MgO (30–40%) and, to a lesser extent, in FeO. It contains an average of approximately 40–45% SiO 2which means it has an ultrabasic composition( Chapter 7). Some basic rocks such as eclogite occur in smaller proportions. In the upper mantle (depths to 400 km), the Mg‐rich silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene dominate; spinel, plagioclase and garnet are locally common. These minerals combine to produce generally dark colored ultramafic rockssuch as peridotite, the dominate group of rocks in the upper mantle. Under the higher pressure conditions deeper in the mantle similar chemical components combine to produce dense minerals with tightly packed crystal structures. These high‐pressure minerals are produced by transformations that are largely indicated by changes high pressure in seismic wave velocity, which reveal that the mantle contains a number of sublayers ( Figure 1.2) as discussed below.

Upper Mantle and Transition Zone

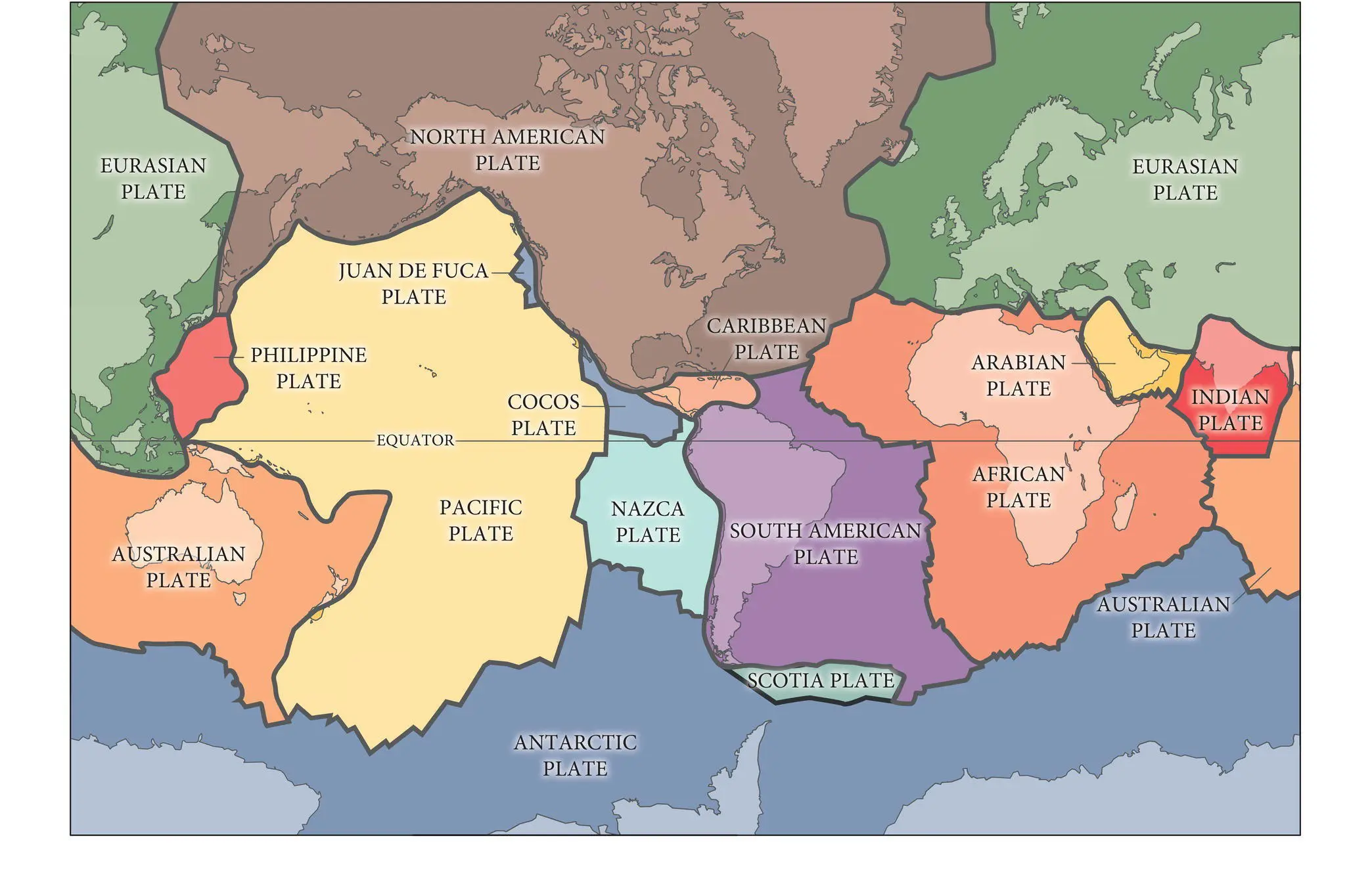

The uppermost part of the mantle and the crust together constitute the relatively rigid lithospherewhich is strong enough to rupture in response to Earth stresses. Because the lithosphere can rupture in response to stress, it is the site of most earthquakes and is broken into large fragments called plates, as discussed later in this chapter.

A discrete low velocity zone (LVZ)occurs within most areas of the upper mantle at depths of ~100–250 km below the surface. The top of low velocity zone marks the contact between the strong lithosphere and the underlying, weak asthenosphere ( Figure 1.3). The asthenosphereis more plastic than the lithosphere and flows slowly, rather than rupturing, when subjected to stress. The anomalously low rigidity of the LVZ has been explained by small amounts of partial melting (Anderson et al. 1971). This is supported by laboratory studies that suggest peridotite should be very near its melting temperature at these depths due to the high temperature. This is especially likely if it contains small amounts of water or water‐bearing minerals. Below the base of the low velocity zone (250–410 km), seismic wave velocities increase ( Figure 1.2) indicating that the materials are more rigid solids. These materials are still part of the relatively weak asthenosphere which extends to the base of the transition zone at 660 km.

Seismic discontinuities marked by increases in seismic velocity occur within the upper mantle at depths of ~410 and ~660 km ( Figure 1.2). This interval (~410–660 km) is called the transition zonebetween the upper and lower mantle. The sudden jumps in seismic velocity record sudden increases in rigidity and incompressibility. Laboratory studies suggest that the minerals in peridotite undergo transformations into new minerals at these depths. At approximately 410 km depth (pressures of ~14 GPa), olivine (Mg 2SiO 4) is transformed into more rigid, incompressible beta spinel (β‐spinel), also known as wadleysite (Mg 2SiO 4). Within the transition zone, wadleysite is transformed into the higher pressure mineral ringwoodite (Mg 2SiO 4). At approximately 660 km depth (~24 GPa), ringwoodite and garnet are converted to very rigid, incompressible perovskite [(Mg,Fe,Al)SiO 3], also known as bridgmanite (Tschauner et al. 2014) and oxide phases such as periclase (MgO). The mineral phase changes from olivine to wadleysite and from ringwoodite to perovskite are inferred to be largely responsible for the seismic wave velocity changes that occur at 410 and 660 km respectively (Ringwood 1975; Condie 1982; Anderson 1989). Inversions of pyroxene to garnet and garnet to minerals with ilmenite and perovskite structures may also be involved. The base of the transition zone at 660 km marks the base of the asthenosphere in contact with the underlying mesosphere or lower mantle ( Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Major layers and seismic (p‐wave) velocity changes within Earth; showing details of upper mantle layers. Colors are as for Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.3 World map showing the distribution of major plates separated by boundary segments that end in triple junctions.

Source : From USGS.

The lower mantle (mesosphere)

The lower mantle, also called the mesosphere, extends from depths of 660 km to the core–mantle boundary at approximately 2900 km. Based on high pressure, high temperature laboratory studies, bridgmanite [(Mg,Fe,Al)SiO 3], ferropericlase [(Mg,Fe)O], magnesiowustite [(Mg,Fe)O], stishovite (SiO 2), and calcium‐rich ferrite (Ca,Na,Al)Fe 2O 4are thought to be the major minerals in the lower mantle. Our knowledge of the deep mantle continues to expand, largely based on high temperature, high pressure laboratory studies and on anomalous seismic signals deep within the Earth. A deeper layer has been proposed at about 1600 km depth where the rigidity of the mantle may increase considerably (Miyagi and Marquardt 2015). Anomalous seismic velocities are particularly common in a complex zone, of variable thickness, near the core–mantle boundary called the D″ layer. The D″ discontinuity ranges from ~130 to 340 km above the core–mantle boundary. Williams and Garnero (1996) proposed an ultra‐low velocity zone (ULVZ) in the lowermost mantle on seismic evidence. These sporadic ultra‐low velocity zones may be related to the formation of deep mantle plumes within the lower mantle. Other areas near the core–mantle boundary are characterized by anomalously fast velocities. Hutko et al. (2006) detected subducted lithosphere which had sunk all the way to the D″ layer and may be responsible for the anomalously fast velocities. Deep subduction and deeply rooted mantle plumes support some type of whole mantle convection and may play a significant role in the evolution of a highly heterogeneous mantle, but these concepts are still controversial (Foulger et al. 2005).

1.4.3 Earth's core

Earth's coreconsists primarily of iron (~85%), with smaller, but significant amounts of nickel (~5%) and lighter elements (~8–10%) such as oxygen, sulfur and/or hydrogen. A dramatic decrease in P‐wave velocity and the termination of S‐wave propagation occurs at the 2900 km discontinuity which is Gutenberg discontinuityor core–mantle boundary (CMB). Because S‐waves are not transmitted by nonrigid substances such as fluids, the outer coreis inferred to be a fluid. Geophysical studies suggest that the Earth's outer core is a highly compressed liquid with a density of ~10–12 g/cm 3. Slowly circulating molten, iron‐rich, very viscous liquids in the outer core are believed to be responsible for the production of most of Earth's magnetic field.

The outer/inner core boundary, the Lehman discontinuityat 5150 km, is marked by a rapid increase in P‐wave velocity and the reemergence of low velocity S‐waves. This suggests that the inner coreis rigid. The inner core is solid and has a density of ~13 g/cm 3. Density and magnetic studies suggest that the Earth's inner core also consists of largely of iron, with nickel and less oxygen, sulfur, and/or hydrogen than the outer core. Seismic studies have shown that the inner core is seismically anisotropic; that is seismic velocity in the inner core is faster in one direction than in others. This has been interpreted to result from the parallel alignment of iron‐rich crystals or from a core consisting of a single crystal with a fast velocity direction. Recent discoveries suggest that the inner core is divided into two layers with the inner layer more rigid than the outer one and with a different orientation of its fast seismic wave direction (Ishii and Dziewonski 2002; Wang et al. 2015).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth Materials»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth Materials» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth Materials» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.