1.4. Creating a game about geographical points of reference

In order to determine the place and the forms that geographical points of reference can take in the context of disciplinary teaching, I conducted an experiment in a school setting, specifically in a classroom I led one-third of the time (departmental discharge) during the 2018–2019 school year, a CM2 (US equivalent of sixth grade) class with 26 pupils at Jean Jaurès School, which is part of the REP+ network, in Tourcoing. It involved building a game which had the goal of acquiring knowledge about a number of spatial points of reference, with these to be located on maps based on their features.

Raising the question of geographical points of reference, even at the CM2 level, is not easy to do. It is not an exaggeration to say that the discipline of geography is barely known there, if at all: it is overshadowed by history even in elementary school (mixed workbooks in which geography is generally located at the end in anticipation of an excess of history) and sometimes is still confused due to its shared prefix with geometry, which is well established in early elementary school and is more present in schedules and general usage. However, the map constitutes a disciplinary marker (Reuter 2007) on which it relies, even if it is not effectively understood by pupils. Whatever the case, a geographical point of reference is locatable on a map.

The problem lies in the fact that maps are present as constitutive elements of learning in the discipline, but they are also very often simply observed without being used. How many classrooms have wall maps, whether it is a traditional map in the style of Vidal de la Blache that has not been updated or a more recent format, which has been hanging on the wall for several years without having been referred to effectively and regularly by the teacher?

However, pupils seem to profess some interest in the knowledge of places from all sorts of perspectives: some are fascinated by flags, others by a mastery of World Cup soccer teams, both of which coincide with their personal schedules, which, just before beginning middle school, become rather important.

It is in the context of these observations that the idea to build a game relating to the theme of points of reference developed: a game that would have an “important but in no sense exclusive place” (Jacob and Servais 2017), a tool to accompany the curriculum and to serve it, even a pretext for diving into the sequence of learning. As Chevalier has shown, the question of memorization has already been addressed from several angles (verbal, iconic, gestural), but it remains despite everything understudied by geographers (Chevalier 2016). Thus, this study intends to add a stone to this edifice by aiming to make of spatial points of reference something more than a component of learning geography, trying in this way to avoid the implementation of “dry nomenclature”.

The creation of a mechanism in the form of a game had the goal of turning this co-designed and co-produced object into a real didactic tool: a tool that would be both defined by its materiality (it would be manipulable) but also by its symbols (it would include a photo of the relevant geographical point of reference as well as clues to help characterize and locate it).

Over time, the goal is to contribute to the systemization of or at least to a relationship between this object and other objects like it, namely other maps that exist elsewhere, either in the classroom (other wall maps, maps in textbooks or handouts distributed by the teacher) or outside (in other reading activities or via other media). How does this co-developed tool make it possible to move toward more abstraction and generalization when encountering non-manipulable maps?

Once again, the 2015 curricula provide complete latitude in the choice of points of reference, which facilitated the creation of such a tool.

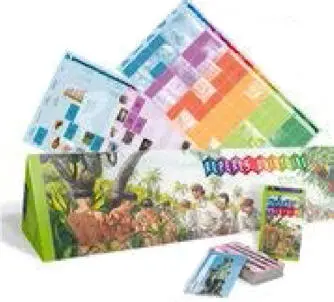

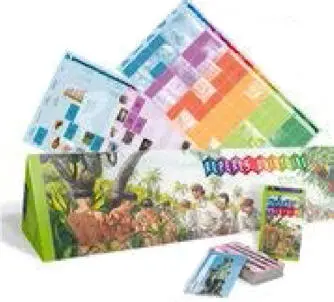

To familiarize pupils with the spirit of the game I wanted to play with them, a few introductory sessions were carried out with a similar historical tool, the Repères d’histoire timeline published by Accès. The idea was to place temporal points of reference onto a chronological timeline, which was identified on the front of the small cards by an image and on the back by three clues with decreasing difficulty ( Figure 1.1). This tool was developed to counteract a lack of knowledge about historical points of reference and in response to already filled-out wall timelines presented without having been built.

Figure 1.1. The Repères d’histoire chronological timelines

A few weeks after the beginning of the school year and after having introduced the historical points of reference game, the project of creating a tool to contribute points of reference in space in parallel to those in time was proposed to the pupils.

To have a basis for departure, the pupils, individually in writing at home, chose ten points of reference that were important to know in their opinion and that could be located on one or more maps.

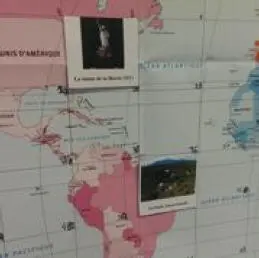

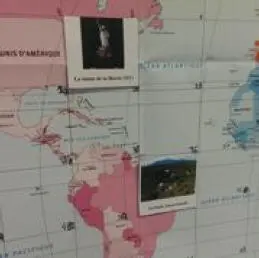

After this study, three wall maps with different scales were posted (France, Europe, the world) with regions, States and continents differentiated by colors and divided into squares to receive the small cards of the points of reference ( Figure 1.2). The goal was to crisscross the space with a consistent mesh, without following State contours, so that they would not only be recognized by their appearance, with the risks this brings (Charlet 2011).

Figure 1.2. Appearance of the game about geographical points of reference

The pupils then began to create the three sentences that would make it possible to define and guess the relevant point of reference, along with a photo for illustration.

1.4.2. What points of reference were chosen initially?

Given that geography does not have a monopoly on space and that the audience for this training was very heterogeneous in its spatial knowledge (Merenne-Schoumaker 2012), it is not surprising that there was a wide range of responses among the first suggestions for spatial points of reference. The pupils did not arrive “without anything”, especially in CM2, and they deployed knowledge constructed by interactions between the academic and personal environments. This reinforces the idea that geographical knowledge functions as a system, which makes school geography one of the poles that benefits from the contributions of university geography, applied geography and, in the context of our current focus here, mainstream geography (Chevalier 1997). The didactics system takes these elements into account by adapting the typical representation, which is usually modeled in the form of a triangle between the pupil, the teacher and knowledge (traditionally “academic”), into a diamond shape for which the additional point is made up of media and vernacular knowledge (Labinal 2012).

The instructions were thus as follows: “Find ten locations you consider important to know about and to be able to locate” (responses presented in Tables 1.2– 1.5). A priori clear enough to be understood and open enough to not bias the responses, this formulation still confused some pupils, since some of the responses ( Table 1.2) were organized around places that could be considered “general”, important to everyone (town hall, hospital, police station, etc.) or for themselves (home, school, garden, etc.) but that could not be located on a map larger than a town, neighborhood or even a specific home: a first set which represented the characteristic “uninformative for others” (Leroux and Verherve 2014) and that could not be used for the remainder of the project.

Читать дальше