For a long time, the prerogative of geography in its classic period (first half of the 20th century) entailed that the study of locations in the form of inventories was also central to geography as it was taught, where a dominant weight was accorded to the observable forms, to the learning of a nomenclature, whether a nomenclature of these forms or of proper names…” (Audigier and Tutiaux-Guillon 2004). While teaching in the discipline today has been heavily modernized (with the presence of a dynamic, albeit fragmented, didactics and an introduction of content with a better connection to the epistemology of the science of reference), we note that “these old forms of school geography persist in mainstream geography” (Chevalier 1997), such as the recent publication of work that exhumes old maps 1or Internet games that are among the top results in Internet searches 2.

What remains clear, in the framework of a prescribed, revitalized school geography, heretofore focused on reasoning and problem solving, dialoging with other disciplines, and integrating representations and the digital, is that learning points of reference in space remains a strong component of the discipline as it is taught, and that we approach it from the perspective of objectives or competencies (Mérenne-Schoumaker 2012). Sometimes taken to be an “ideal-type of transmission of a self-centered vision of the world”, among other things “by filling the function of common culture destined for disadvantaged pupils” (Thémines 2004), the question of the geographical points of reference to be studied resonates more sharply in the framework of what we were interested in here, elementary school teaching, where teachers, who are generalists, are only suited for the discipline’s “surface elements” (Philippot 2008) because of their “imperfect polyvalence” (Philippot and Baillat 2011) and who consider this mastery of points of reference as an indispensable prerequisite for other forms of teaching, sometimes even beyond what is called for (Leroux and Le Bourgeois 2020).

If this need to present points of reference as an essential foundation sends school teachers back to the geographic education they received as pupils or to mainstream geography, another explanation lies in the fact that the study of locations and points of reference can be easily evaluated, which can lead to it being considered as a “low stress intellectual operation” (Mousseau and Pouettre 1999), which results in “factual errors” (Hugonie 2002). A glance at the forums and blogs of elementary school teachers shows real resource-sharing in terms of teaching resources suggested by teachers that seem legitimate because of their knowledge as “practitioners” and because users indicate satisfaction with them (Baudinault 2017). Assessments on points of reference are included, but the gap between prescribed geography and geography as it is practiced inevitably exists. In a study conducted by the DEPP, in the framework of the CEDRE (Cycle of Disciplinary Evaluations Conducted by Sample) in 2011, almost 75% of the elementary school teachers in the fields of history and geography who responded rejected the assertion that their assessments consisted of “reciting a lesson”, even though 85% of them recommended “memorization of the lesson” (SCEREN CNDP-CRDP 2011)!

1.3. Points of reference in upper elementary curricula

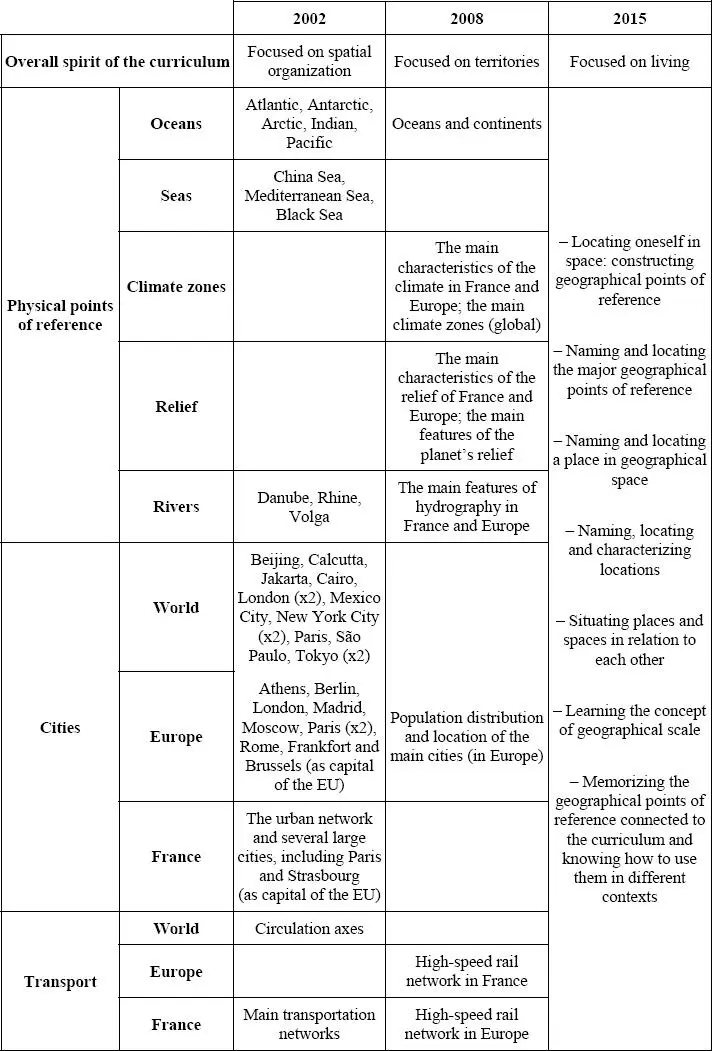

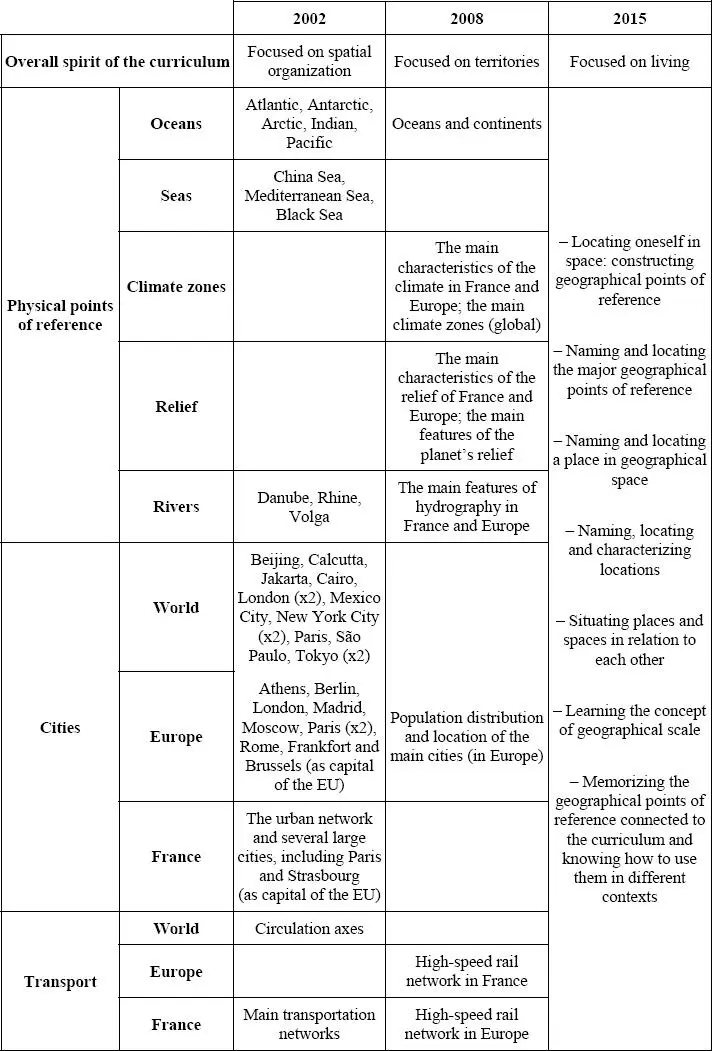

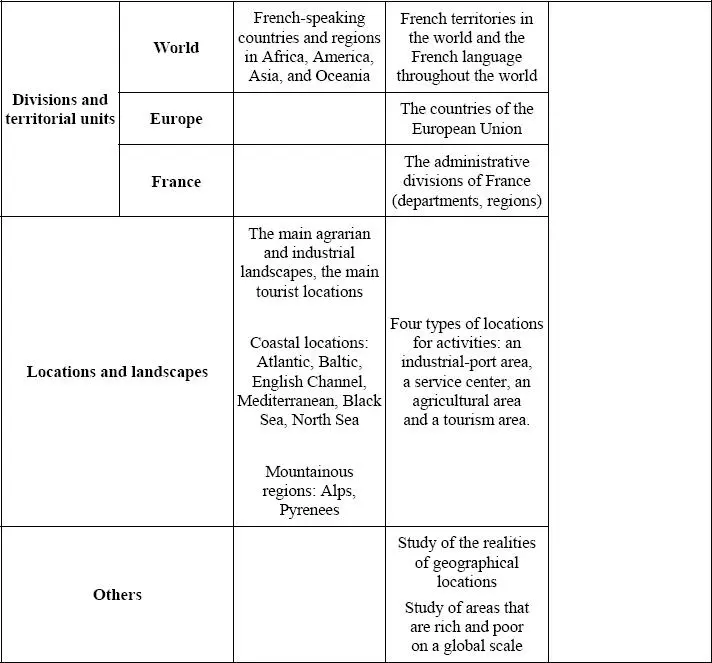

Points of reference thus constitute an unavoidable component of learning geography, but they are specified inconsistently by the various official directives. A comparison of three sets of curricula is necessary for two superimposed reasons: first because the most recent provide no orientation or even list for determining the points of reference that are nevertheless required, and second because the very frequent changes in the curriculum do not aid the “slow infusion of geographical knowledge” (Baudinault 2017). Elementary school teachers do not have the time, the assistance or the perspective to absorb and interpret these changes; they struggle with the current curriculum, particularly with regard to the importance to be accorded to points of reference, and they do not change their habits easily. Table 1.1shows these three curricula (2002, 2008 and 2015), which merit several comments.

The most general is that, despite paradigm shifts, particularly in the latest concerning “living”, which profoundly revitalizes the way of understanding the world, points of reference are still present, and they even set the boundaries for a strong competency organized around several elements: naming/describing or identifying/locating or situating. These terms are not neutral, and it is their complementarity that allows for the achievement of complete mastery of this vast skill, which is the “construction of geographical points of reference.” The study conducted in 2011 by the DEPP specifies with regard to elementary school that “the attribute or function of a place and the mastery of a specific lexicon results in higher grades than locating it on a map”. However, a 2008 assessment booklet by the same SCEREN network, called the “elementary school booklet” or the “blue booklet”, only includes a single skill for geography in upper elementary school: “Identify the primary features of the geography of France”: quite a vague heading given the lacunae observed in the study.

Another point relates to the degree of precision and imperativeness with which these points of reference are treated. While the 2002 and 2008 texts mention “primary points of reference”, the 2015 text mentions “major points of reference”. A priori , there is not much difference between these terms, as they can be interpreted to refer to the essential points of reference, those that are most important. Where things differ more clearly is in the use of definite or indefinite qualifiers for determining these points of reference. Each of the three texts includes clearly identifiable elements such as “the” oceans, countries, French-speaking regions, etc., with the support of specific lists (2002), but areas of vagueness can be seen in expressions such as “some” large cities (2002) and “some” spaces (2015) or the use of ellipses (list of large global cities in the 2002 text). While the three texts mention the points of reference to “know”, the 2008 curriculum intensifies the word by mentioning “indispensable” points of reference to be mastered, which can be complemented by other elements chosen by the teacher.

Table 1.1. Points of reference in upper elementary curricula for 2002, 2008 and 2015

Another point of analysis can be seen in the “World” table appended to this text: which map of the world is proposed by the legislation? The texts become less precise as time goes on. The 2002 curriculum is very detailed and does not hesitate to name seas, rivers, cities and locations. What we find there are more or less the cities of school culture (Clerc 2002). The role of the European Union appears clearly, with locations shown in a network. The 2008 text, which caused an uproar because of its archaic and Franco-centric nature (Roumégous and Clerc 2008; Leroux 2012), did not achieve its predecessor’s level of precision, but did provide groups of points of reference to be learned. In addition to the preceding physical elements (climate, relief), elements related to administrative divisions (countries of Europe, French departments and regions) were added. The current curriculum gives teachers a wide margin for maneuver by only specifying that these points of reference can be places or areas. It specifies that “geographical points of reference related to the curriculum should be memorized” and, in the introductory chapter, that “contextualization, putting the place being studied into relation with other places and with the world, provides the opportunity to continue work on major geographical points of reference”. If all this seems advantageous for learning the multi-scale method in support of the skill of “understanding the concept of geographical scale” that is also mentioned in the curriculum, the question of knowing which points of reference will actually be presented by teachers in their classrooms remains open.

Читать дальше