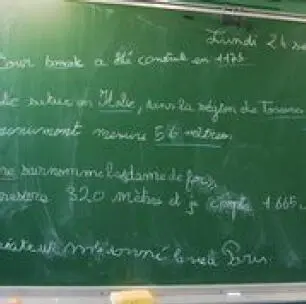

Next, while reading the clue sentences, we should stop to consider the pupils’ attempts to be sufficiently explicit in the clue linked to the location. For example, Figure 1.3(dated September 24) shows that it is possible to mention just the city (“My creator gave me life in Paris”, for the Eiffel Tower – number 2) or to add precision to a regional subset (“It is located in Italy in the region of Tuscany”, for the Tower of Pisa – number 1). The arrow in the table indicating a potential inversion of clues 2 and 3 shows that the location clue did not necessarily have a “natural” location in position 1, 2 or 3. However, during the game, when a pupil knew all of the points of reference in the game, it was still possible to find the point of reference based on the first clue if the point of reference was the only one in the country/city. Sometimes, other details were necessary. To guess the Easter Island statues (number 6), it was useful to indicate the latitude “in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Chile”, which led the pupil to locate Chile. It was also necessary to pay attention to the cumulative aspect of the points of reference in the game. If the Statue of Liberty (number 3), initially the only point of reference in the United States, could be defined as “offered by France to the United States, specifically to New York City”, the addition of Hollywood (number 12) required adding the detail of being located “in Los Angeles, on the West Coast of the United States”. Thus, a pupil who could not locate New York City could, by eliminating Los Angeles on the West Coast, deduce that it was located on the East Coast. This invited use of the cardinal points for locating places. Finally, a comment can be added with regard to the zonal aspect of a point of reference. While a spatial point of reference naturally appears as a point (city in a country, building in a city), nothing prevents it from being a line (a river, for example) or an area. Here, the sprawl of the Amazon forest (number 4) over several states required it to be defined as “being home to a significant biodiversity”. In the same way, animal territories are not circumscribed by state borders, and so it was necessary to show that the country indicated was only an example among others for the image of the giraffe (number 23): “I am found in the African savanna; for example, in Kenya”.

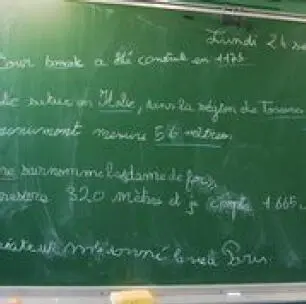

Figure 1.3. Clue sentences. Translation: This leaning tower was built in 1173. It is located in Italy in the region of Tuscany. This monument measures 56 m. My nickname is "the iron lady". I am 32 m tall and I have 1665 steps. My creator gave me life in Paris

Finally, with regard to the skill of finding locations in space, which is only a part of the study of geography, this game complemented more traditional class sessions focusing on the study of documents that aimed to develop an analysis of the organization of space by humanity, which is the essence of the discipline. I also tried when possible to make the connection between the points of reference suggested by the pupils which I had already incorporated into the curriculum for the year. Thus, the strong presence of monuments, particularly towers (number 1 – Pisa, number 2 – Eiffel, number 11 – Burj Khalifa, number 21 – Tokyo) gave me the opportunity to address, from the very beginning of the year, the question of available urban space and the recourse to vertical building when there’s not enough space to spread out on the ground. The sequence allowed me to conduct a session on comparing the height of the world’s skyscrapers (including Burj Khalifa Tower) and those in France (including the Eiffel Tower), as well as a session on errors in architecture and territorial management, highlighting the technical errors that led to the Tower of Pisa’s leaning immediately after construction. While I thought about theme three for CM2, “Better living”, which I initially scheduled for the end of the year, this sequence pulled forward the initial questions about building tall buildings to the beginning of the year, which made it possible to connect the pupils’ thoughts and mine about finding locations and how they are organized. Other points of encounter could have occurred in a timelier manner. Theme one of CM2, “Traveling”, provided the opportunity to think about types of transportation (the use of rivers: number 17 – the Corinth Canal), migration following natural disasters (volcanism: number 20 – Piton de la Fournaise volcano) and the potential for migration caused by climate change (the measurement of climate at scientific stations: number 5 – Dumont d’Urville Station). It was not always possible to find a connection: variations in the ability to create these links constituted one of the explanations for the project running out of steam and for the subsequently necessary relaunches. This element was, nevertheless, indispensable for preventing the practice of learning points of reference from becoming one of “dry nomenclature”.

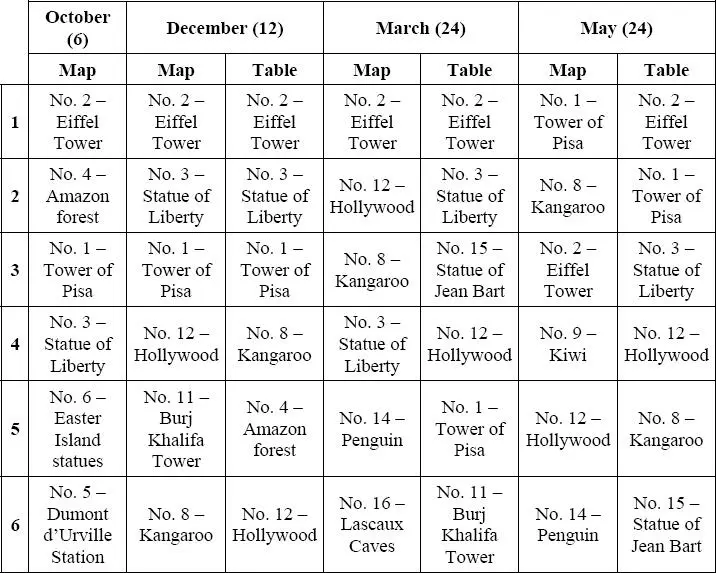

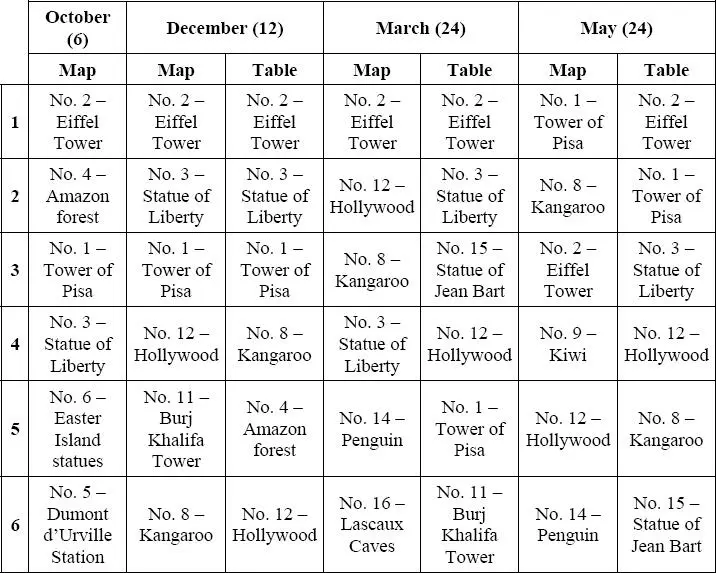

What can we say about the evaluation of this mechanism? To understand and take account of the activity, I chose to suggest, in addition to the collective wall version, other copies of the three maps (world, Europe, France) with clue labels for the pupils so they could practice, in groups, during free work time, identifying and locating the points of reference. In addition to this form of training, which was threaded and codified through the year, four more formal evaluation periods were regularly spaced through the year (October, December, March, May). Table 1.7shows the results of the six best results in relation to the set of points of references used during each period (6 in October, 12 in December, 24 in March and May). In October, I chose to provide the pupils with a simple planisphere because there were only six points of reference. For the three other periods, I used a two-page spread (A3) including all of the maps (planisphere, map of Europe, map of France) to be clearer, as well as a table where the pupils could fill in the names of cities, countries and continents as necessary for each point of reference. This protocol was important because some pupils preferred to fill out the table, where they sometimes found it easier to identify the spatial relations, before beginning to fill out the maps.

Table 1.8shows the frequency of cumulative responses for the maps and tables, with a number of elements worthy of interpretation. We can see at once the heavy weight of the oldest points of reference: the first three points of reference suggested (number 1 – Tower of Pisa, number 2 – Eiffel Tower, number 3 – Statue of Liberty) were precisely the three most successfully identified points of reference. We can also see a strong centering on the global scale, since the Tower of Pisa was the only representative in Europe (in green), and the low number of occurrences for the statue of Jean Bart and the Lascaux Caves, which only weakly reinforced the total number attributed to France (in blue). America (in pink), especially the United States, was the dominant continent for identifications on a global scale. Animals occurred somewhat frequently, such as the kangaroo and the kiwi for Oceania (in orange) and the penguin for Antarctica (in black). Asia (in red) was only weakly represented, with two occurrences of the Burj Khalifa Tower.

Table 1.7. Evaluation of points of reference through the six most frequently correct identifications

The pre-eminence of the oldest points of reference in the list of those most precisely identified was magnified by an affective dimension (spatial and cultural proximity of the Eiffel Tower as the symbol of France, the strong cultural and linguistic influence of the United States and a childhood sensitivity toward animals). However the successes/failures had other spatial explanations: the inclusion of the penguin despite the continent of Antarctica’s lack of development indicates that the pupils had grasped the idea of climate zones; the infrequent occurrence of the Amazon forest and the absence of capoeira indicates that they were located too close together, causing confusion, and that the map had to be read more carefully (the point of reference for capoeira pointed to the center of Brazil, while the Amazon forest was located at the country’s borders); the statue of Jean Bart was legitimately more local for pupils from Tourcoing than the Cliffs at Etretat or the Château de Pau.

Читать дальше